Light in the Tunnel?

By Kunwar Khuldune Shahid | News & Politics | Published 9 years ago

A review of Pakistan’s counter-terrorism endeavours for 2015 would inevitably trace their point of origin to December 16, 2014. It took an act of terror as gut-wrenching as the APS massacre to ‘unite’ the nation. The terrible massacre of children and teachers laid bare what had been ominously obvious for a decade: that the radical Islamists were no ‘freedom fighters,’ and that jihadism would boomerang on the state, which had spent decades allowing it to brew. While sectarian attacks and indiscriminate bombings from Lahore to Parachinar and from Khyber to Karachi, had continued unabated for years, with successive governments seeming to have neither the will nor the wherewithal to fight the terrorist demon, it took Peshawar to finally jolt the authorities into action.

On December 17, Chief of Army Staff (COAS) General Raheel Sharif visited Kabul, seeking the extradition of Mullah Fazlullah, the chief of the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which had claimed responsibility for the APS attack. General Sharif also met the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) commander, Gen. Joseph Dunford, ostensibly providing him evidence of the TTP’s ‘safe sanctuaries’ in Kunar and Nuristan.

The same day the Prime Minister convened an All Parties Conference (APC), where it was decided to draft a plan of action against terror groups, and the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI) Chairman Imran Khan said he would discontinue his anti-government movement in Pakistan to signify ‘political unity.’ In a candid admission of the government’s failed earlier policy of separating ‘bad’ Taliban from ‘good’ Taliban, Nawaz Sharif vowed to address all terrorists, Taliban, et al, alike. This vow formed the bedrock of the National Action Plan (NAP) that was chalked out, designed to decisively deal with Pakistan’s security predicament. And with the two Sharifs addressing the foreign and domestic sources of terror on the same day, it seemed that Pakistan’s counter-terrorism battles would be fought on all fronts.

On December 24, all the country’s political parties met to finalise the setting up of military courts to ‘tackle terrorism’ in the country. “We have to act fast, and we have to immediately implement whatever is agreed upon. This agreement is a defining moment for Pakistan. We will eliminate terrorists from this country,” the Prime Minister said at the meeting. Later the same evening, on a national TV address, he announced the formulation of the NAP.

The 20-point plan sought to tackle terrorism in a myriad ways, and even the harshest cynic wouldn’t claim that Pakistan has completely failed to implement the plan, or that there hasn’t been any tangible difference in government — or establishment — policies in regard to terrorism. The statistics speak for themselves. Last year Pakistan saw the fewest casualties linked to extremist attacks since 2007.

The figures notwithstanding, it is hard to argue against the claim that the state hasn’t been able to implement its own, much-touted, National Action Plan with the kind of zeal required to get the job at hand done, and has, in fact, acted more akin to its sardonically prophetic acronym.

While swift trials are important, blanket accountability — executions of child offenders alongside those of victims of unfair trials, especially those tried in secret by military courts without civilian oversight, or selective accountability — take Taseer assassin, Mumtaz Qadri’s case — obviously make the judicial process questionable. The human rights debate over the judiciousness of capital punishment can be countered by highlighting the state of war Pakistan is in, but reckless executions or politically delayed justice will always divide the nation.

While the government has decided to ensure that no further armed militias are formed and the ones existing are outlawed, token bans won’t suffice in actually countering the activities of banned militant organisations. Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) supremo, Malik Ishaq’s ‘execution,’ is no more proof of the government targeting the LeJ, than Azam Tariq’s ‘execution’ was of the authorities’ intent against the Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP). The banned SSP morphed into the political organisation, the Ahl-e-Sunnat Wal Jamaat (ASWJ), and its militant offshoot, the LeJ, is still alive and active as demonstrated by the attack by LeJ operatives in Parachinar, which killed 25 and injured 70 in December. With Shafiq Mengal and Kabeer Shakir still around, and Ahmed Ludhianvi continuing to fight cases in the state’s apex court over his National Assembly seat from Jhang, it is obvious that the sectarian monster, the ASWJ, wasn’t quite beheaded along with Ishaq, and is, in fact, capable of growing new heads. One such head is the Pakistan Rah-e-Haq Party (PRHP), an ASWJ affiliate that won seats in November’s local bodies elections in Sindh.

As the country’s anti-Shia political organisations rechristen themselves to participate in grass-root — and national — politics, with affiliated militias orchestrating terror attacks in blatant defiance of the NAP, it becomes obvious that they, particularly the eastward-bound ones, have been given a conspicuous pass to operate with impunity. Hafiz Saeed, the chief of the Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD), the ban on which is still being mulled, has made no secrets of his affiliation with the ‘Kashmiri jihad’ — a historic euphemism for conducting proxy terror in Kashmir and India — and the Mumbai attacks in 2008. The JuD is to the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) what the ASWJ has been to the SSP. Saeed’s ability to circumvent the law, his regular appearances on television alongside LeT leader, Zakiur Rehman Lakhvi, and the fact that they are constantly shielded from questions regarding the Mumbai attacks, openly contradict over a quarter of the NAP’s 20 points.

As far as impunity is concerned, however, no one is a bigger recipient than the Lal Masjid’s Maulana Abdul Aziz, who has been challenging the state’s writ from the capital. His vocal support for IS in the lead-up to the APS attack, coupled with his flagrant announcement of a movement to enforce Shariah in November, was an act of open defiance against the NAP and Pakistan’s Anti-Terrorism Act (1997). This clearly indicates the fact that there are still many individuals who are bigger than the government’s action plan designed to challenge terrorism in ‘all shapes and sizes.’ And this even against the backdrop of the recent meeting between US and Pakistani officials over Tashfeen Malik, the Pakistani female attacker in the San Bernardino shooting, and her links to Lal Masjid.

Federal Interior Minister, Chaudhary Nisar Ali Khan’s response to Abdul Aziz’s protection from law is the fallacious claim that “there are no registered cases against Aziz.” Notwithstanding the much publicised FIR against Aziz, his march from Lal Masjid to Jamia Hafsa in November should have resulted in his arrest, especially after Aziz threatened to “tear” the government’s notice on the ATA breach “to pieces.”

As is increasingly evident, Nisar and the interior ministry’s efforts to eradicate terror have been dedicated almost exclusively to curbing the “foreign funding” and “anti-state activities” of International Non-Government Organisations (INGOs).

On October 1, the federal Interior Ministry announced, via a new policy, that all INGOs would be required to apply online for registration within 60 days. While registration and monitoring of INGOs is unarguably important, what is equally important is the implementation of a system on this front that isn’t open to the interior minister’s interpretations. For instance, the government’s INGO policy doesn’t even define an INGO coherently. Secondly, the vagueness of terms like “anti-Pakistan activities” and “anti-state elements” leave even the most reputable NGOs open to abuse, as we earlier witnessed with the fiasco surrounding Save the Children and their operations in Pakistan. That this charity remains banned in KP and Balochistan, highlights the state’s paranoia vis-Ã -vis those two provinces, and jeopardises the potential work that INGOs can do in areas where their work is most needed.

It is safe to say that if the Interior Ministry showed one tenth of the intent it is exhibiting to streamline INGOs on moderating and reforming madrassahs, Pakistan might actually be closer to targeting the roots of jihadist ideology. With absolutely no effort on the madrassah front, except the year-end verdict that 285 seminaries in Pakistan are foreign-funded, jihadism continues to be brewed in the garb of religious education. That there has been no concrete effort to even design a pluralistic curriculum for the madrassahs that incorporates progressive thought and worldly education, shows that the state is still light years away from countering the extremism that madrassah students continue to be indoctrinated with, and the hate speech that continues in these institutions unchecked and unfettered.

Giving the Balochistan government more authority to counter militancy was crucial to insurgency in the province. And yet, all talk of Baloch autonomy is diminished by the shadow of the Murree Accord. The federal government continues to pull all the strings in Balochistan, with the establishment continuing its ‘lift and dump’ policy which has left over 20,000 missing in the province. The reported talks between Brahamdagh Bugti and state officials over a possible return to Pakistan in exchange for abandoning the separatist insurgency he was spearheading was one of the few positives in the security situation of the province — a situation which is at the heart of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Peddled as the ‘economic lifeline’ of Pakistan going into 2016, it has proven itself to be the ‘security lifeline’ of the country as well, with Beijing fast-tracking counter-terrorism manoeuvres along the multi-pronged CPEC routes.

The CPEC wasn’t the only positive for Pakistan’s security in 2015. The almost back-to-back deaths of former DG-ISI Hamid Gul and the Punjab home minister, Shuja Khanzada in August, were symbolic in many ways. As Gul remained an integral part of Pakistan’s jihadist past and present, many hoped Khanzada — who was killed by an LeJ attack at his office near Attock — would become the face of Pakistan’s counter-terror future. Khanzada had arrested over 3,000 people for chanting anti-Shia slogans since his appointment in October 2014, and he openly condemned the hate speech echoing from mosque loudspeakers all over the Punjab. Khanzada’s no-nonsense approach to Islamist extremism is what Pakistan needs to learn from, going into 2016.

Two historic Supreme Court verdicts also hinted at Pakistan’s intent to right historic wrongs. In July the SC suspended Asia Bibi’s death penalty over her alleged blasphemy, while in October a three-judge bench, headed by Justice Asif Saeed Khosa, scrapped the plea against Qadri’s death sentence. The court accepted the government’s appeal against the Islamabad High Court, which had dropped the terrorism charge against Qadri for the murder of Salmaan Taseer in 2011. Maintaining Mumtaz Qadri’s terrorist label wasn’t just symbolically important, but the twin verdict also makes it twice as difficult for the defence counsel to help their client escape through legal means.

Arguably, what was even more crucial than the verdict against Qadri, was Justice Khosa’s commonsensical — and groundbreaking — assertion that “criticising a law does not amount to blasphemy.” This could herald the much-needed reform in the blasphemy law, which has been responsible for violence against religious minorities since the addition of Sections 295-B and 295-C in the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC), which give preference to the religious sentiments of Muslims over other religious communities.

While the incident in Jhelum, where an Ahmadi owner’s factory was torched and the vandalising of the community’s ‘place of worship’ in November, reminded everyone of the Muslim supremacism — as embedded in the constitution — which encourages mob violence, the local police’s efforts were crucial in ensuring that no lives were lost. The Punjab police also removed hate posters (pasted on walls in shops in Hafeez Centre in Lahore for several years) and officially ordered the cessation of hate speech — an unprecedented, and much needed, even if greatly belated move to curb the culture of hate in the country. Even so, the fact that every single Ahmadi had to escape Jhelum following the factory attack and protests calling for Ahmadiyya apartheid simmered outside Hafeez Centre following the police’s action, showcases the clout that the blasphemy law provides Islamist mobs.

No doubt that there are some encouraging signs that engender a little hope. But an honest assessment of the NAP shows that there is still a lot that needs to be done to right the wrongs of the past three decades. Ten years from now, if the state’s security machinery decides to build on the gains from the past 12 months and addresses glaring shortcomings, the year 2015 could be remembered as the turning point in Pakistan’s volatile history. Otherwise, NAP would just have been another shot in the dark in Pakistan’s long history of counter-productive strategies to counter terror.

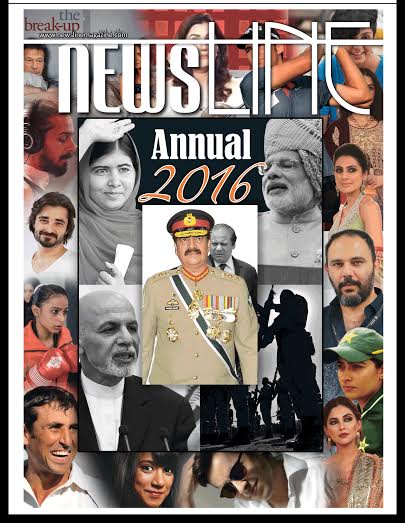

This article was originally published in Newsline’s Annual 2016 issue.

Kunwar Khuldune Shahid is a journalist and writer based in Lahore.