Lasting Image

By Tehmina Ahmed | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 23 years ago

Saeed Khan is a photographer who believes in keeping up with the times. An old hand at the game, he has now chosen to experiment with technique while retaining his interest in a formal approach to photography.

Saeed Khan is a photographer who believes in keeping up with the times. An old hand at the game, he has now chosen to experiment with technique while retaining his interest in a formal approach to photography.

Since the digital age is upon us, even those of us who shrink from the notion of “fixing” images in anything other than the mindÃs eye have to accept the inexorable advances of digital scanning and printing.

Saeed has now switched over to and advocates the use of the ìpigmentî as opposed to the “dye” process in printing. In laymanÃs language, the new technology that has come in with digital printers enables the use of complementary pigment inks and pigment paper to form a long lasting image. While conventional dyes and paper are highly susceptible to the effect of light ñ resulting in colour prints losing their colour over time — pigments are impervious to light and produce light-fast prints. Using a combination of pigment-printing and high quality paper, Saeed is now making prints that will retain their brilliant colour at least “a hundred years.” Talk about archival.

Saeed Khan’s forays into photography began at an early age. His father was a printer, so the feel of paper and the smell of printer’s ink is an early memory. Then, as a schoolboy he began to take pictures with the proverbial box camera. “I took very strange photographs,” says Saeed, almost with a touch of pride.

He is matter of fact about a long career in the course of which he may not have received the recognition he merits. “People who have seen my photographs know me and those who haven’t donÃt know me,” he says, with no sense of chagrin. One gets the idea that being known is not one of the motives behind his pursuit of photography.

The early years were spent in commercial work. Saeed and I reminisce about the good old days and Sasa Advertising where I first met him, more years ago than I care to recall. Before that, he had done a series of calendars for Elite Publishers, an assignment that led him to the field of professional photography.

Saeed had a grounding in science that gave him a natural affinity for the handling of technical issues in photography and film processing. He added on to this with formal short courses in laboratory work. Eventually, Saeed set up a colour lab and then became the first — and only -person in the country to offer direct prints from slides, using the Cibachrome process. Being more of an artist than a businessman, he wasn’t breaking even and gave it up to go back to freelance photography.

Saeed is now gearing up for a long overdue exhibition -his last solo show was held twenty years ago. He is labouring over his prints in a set-up that fits neatly into his study at home. “No more darkrooms,” he says with relief. The computer, printer and scanner producing the archival prints occupy just about a table and a half of space.

While the photographs at first sight may seem to be straight landscapes, taken no doubt with a degree of technical virtuosity, given time, some of them begin to haunt you. They were taken during a seven-year period in the nineties, a time when Saeed had time out from personal responsibilities and could take his eye out for a walk, so to speak.

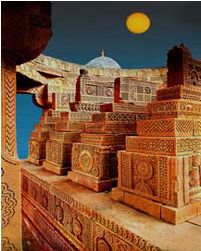

He travelled far and wide, searching for the elusive moment that defines a fine photograph. “I must have travelled two or three thousand miles and taken hundreds of photographs,” he says. From architectural elements in the Moghul monuments of Lahore to the colours of nature, SaeedÃs work reflects the wealth and diversity of our national heritage. Given the dearth of books that display anything beyond the moribund image while portraying Pakistan, I asked Saeed if he had ever tried to compile his work in book form. “I did once, but the project got aborted,” he says, not displaying much regret or desire to revive the “aborted” project. He is a man who is very ambitious in some ways and not at all in others.

There is a wealth of detail in Saeed’s work, along with a studied play on the element of colour. “Some people may see my work as that of a colorist,” he says. ìBut I am much more of a formalist. If you were to see these pictures in black and white you would see what I mean.î And the pictures do stand up to that test, the formal elements of design and composition, of texture and tactile detail being indeed very strong.

The scanner and computer are used to make changes in the original image, a fact about which Saeed is not at all apologetic. Pointing out a landscape with ruins in the background and a field of flowers in the foreground, he says, “I brought these flowers from a different place two miles away to this place.”

Times change, he points out, and it makes sense to change along with them. At the moment, the person who uses digital photography to change or enhance a photograph may raise some eyebrows, but just the existence of the technology ensures that photography will never be the same again.

“There is nothing wrong with a sculptor using a new drill to accomplish his objective,” he asserts. He is all for using a process through which the artist can ìexpand an idea, expand a thought.î Somewhat mysteriously, he says, “I may have something in my sub-conscious mind that only later on becomes what I saw.”

He considers the original photograph a starting point. The camera is a sketchpad, and it is kosher to alter the sketch to more accurately reflect what the photographer had in mind. Of course, photographers have also used the darkroom and enlarger for the same purpose, but the chemical process is more tedious and more limited in terms of the changes it can affect. “The computer gives you much more control,” says Saeed with a great deal of enthusiasm. “It can change the smallest bit, the darkest bit, the lightest bit.”

There is a photograph of the Badshahi Masjid, with ominous storm clouds in the background, clouds that are obviously computer-generated. Discussing the image, I get a clue to the way the process works for Saeed. He describes how he set out to photograph the Masjid and was caught in a sudden spell of rain. By the time he took his photograph the rain was gone. But the image in his mind’s eye was that of the Masjid on a stormy day. So he used his computer to work the clouds back in. “It’s not easy to make clouds on the computer, but you can do it. I made the clouds, but I can’t make squalls of rain,” he says with some regret.

There is a beautiful image of light streaming in through a series of doorways onto the frescoed walls of Ranjit Singh’s haveli. The balance of outside light and gently lit frescoes has been reached through the computer. Not to mention the fact that the process has dusted off coloured pigment dusk from the walls to reveal their inner radiance.

In another image of the walled city in Lahore, the aging original print has yellowed in places while the colours have lost their lustre in others. Saeed shows me a fresh digital print that has restored original colour and brought out detail in a shadowed alley that does not even appear in the original print.

So then, I’m convinced that far from faking images, the thoughtful use of digital technique can not only rescue faded photographs from obscurity, but can also be used as an effective tool to enhance the artist’s palette.

No more posts to load