Killed in Custody

By Adnan Adil | Newsbeat National | Published 6 years ago

Statistics bear testimony to the fact that the police in Pakistan kill more people than any militant group or gangster and enjoy virtual immunity from the law. During the last one month, at least three incidents of deaths in police custody and police torture occurred in the Punjab province within the span of a week. In early September, Salahuddin Ayubi died in police custody in Rahim Yar Khan, while Amjad Zulfiqar and Amir Masih died of police torture in Lahore.

According to the Punjab police’s official statistics, 16 people died of police torture in Punjab in the first eight months of this year. However, unofficial estimates put the number at 52.

On September 2, Salahuddin Ayubi, a mentally challenged man, accused of stealing from an ATM counter, died in police custody in the Rahim Yar Khan district of Punjab. A video clip showed policemen beating and humiliating Salahuddin while he was in their custody. Salahuddin’s father Muhammad Afzaal, who lives in the Gorali village of Gujranwala district, told the media that he had learnt of his son’s arrest on August 30, when a television station ran a video clip showing his son robbing a bank’s ATM machine. The father claimed that the police murdered his son by torturing him in custody. He said he had seen the torture marks on his son’s body – his right arm was burnt and there were bruises on his entire body.

However, the deputy medical superintendent of the Sheikh Zayed Hospital in Rahim Yar Khan certified that the deceased, Salahuddin, bore no marks of torture. The concerned Regional Police Officer (RPO) also denied the claim that he had been tortured before death. The subsequent forensic report exposed the lies of the doctor and the police and verified deep cuts in Salahuddin’s body. After the forensic report was made public, the Punjab police’s spokesman made the routine clichéd statement: “We condemn any form of violence and torture. It could be an individual act. We are investigating whether a police official was responsible for Salahuddin’s death.”

In another case of alleged police brutality, on September 1, Amjad Zulfiqar, accused of trading in narcotics, died at a local hospital in Lahore due to alleged torture by the Gujjarpura police in a private detention cell of the local police. The torture cell was found in a building of the Forest Department, where nine suspects, including Amjad, were illegally kept by the police for interrogation. Amjad’s video surfaced on social media a few days before his death. It showed Amjad lying on a charpoy after the policemen subjected him to severe torture, which led to the fracture of his backbone. In the video, Amjad said he couldn’t even move; he also alleged that the policemen raided his house, misbehaved with his family, took away cash and valuables from his home and locked him in the building of the Forest Department. Later, Amjad was freed but he died during the course of his treatment at a local hospital. The Lahore police high-ups claimed that he had died of cardiac arrest.

As Amjad’s video went viral and media reports built up public pressure, the police launched an inquiry, which was conducted first by a superintendent of police and then by another senior police officer. Both departmental probes found the Station House Officer (SHO) and other policemen guilty of charges levelled by all the nine detainees in the private torture cell. Three of the accused policemen were later suspended from service and a murder case was instituted against them. Intriguingly, Amjad’s heirs refused to follow up on the murder case against the policemen.

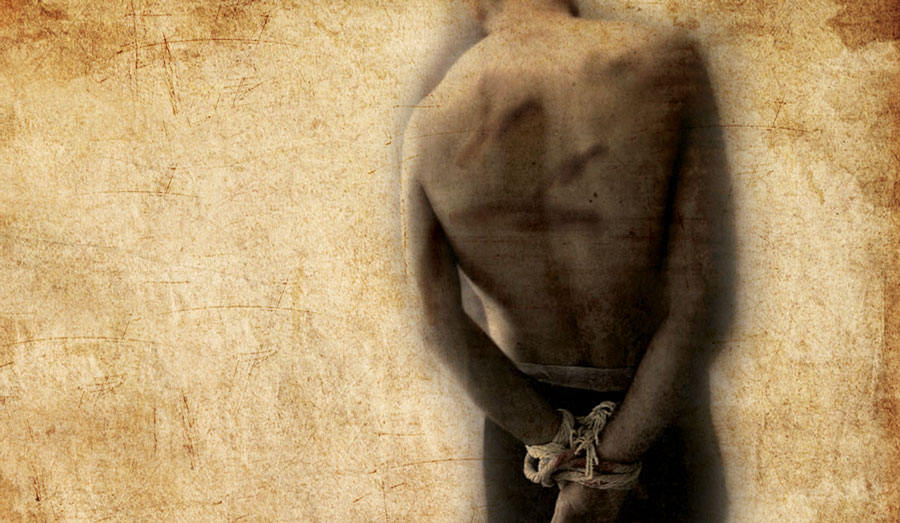

No mercy: Custodial torture led to death of mentally challenged Salauddin Ayubi.

In yet another case, on August 28, Amir Masih, a gardener in the house of a senior retired government officer in Lahore’s PAF Colony, was summoned by a police officer at North Cantt Police Station and was taken to an undisclosed location, where he was allegedly subjected to torture. When Amir’s family contacted the police station, they could not meet the relevant sub-inspector involved in his arrest. On September 2, three police officials handed over a critically injured Amir to his family. He was taken to a local hospital, where he succumbed to his injuries. The police registered a case against six police officials and transferred some senior supervising police officers.

As all these three cases followed in quick succession, a hue and cry was raised in the media causing embarrassment to both the police and the government – but only for a few days. Then some other major events overtook them and all was forgotten. In order to ward off public pressure, the government announced their intent to introduce police reforms, though on the ground nothing has changed.

Being subjected to police torture has become a routine for the poor accused in criminal cases; a rich man never dies of torture in police custody. According to a report of the Centre for Public Policy and Governance, Policing, Custodial Torture and Human Rights in 2013, custodial torture is the prime tool of evidence collection in Pakistan. The most common forms of police torture include suspension by the ankles, severe beating on the soles of the feet, rolling heavy logs on the accused’s legs, giving electric shocks, burning the body with cigarettes, pulling out hair and threatening execution in a fake encounter.

In the feudal set-up of Punjab and Sindh, the police work to suppress the poor and favour the rich and the influential. When a crime takes place against a member of the elite, the police comes under pressure to find the accused and recover the stolen goods or the weapons used in a murder crime, for instance, within the shortest possible time. For example, Amir Masih was nominated as a suspect in a theft case at the house of an influential retired army officer and under the officer’s pressure the police subjected him to the worst kind of torture leading to his death.

The police usually excuse themselves by trying to hide custodial deaths as suicides or outcome of an illness, such as a heart attack. In order to cover their ruthlessness, the police exerts pressure on medical doctors to cover up for them, as in the case of Salahuddin, where the deputy medical superintendent of Rahim Yar khan’s Sheikh Zayed Hospital gave the police a clean chit and said Salahuddin had died of natural causes. Cases are instituted against police officials, but they are seldom convicted. Such atrocities either result in the immediate transfers of police officials or their temporary suspension orders, which are soon reversed.

Experts say one of the main reasons behind the use of torture by the police is said to be the age-old penal laws that lack the mechanism to prevent the abuse of power.

Under the Code of Criminal Procedure 1898 (CrPC), the police enjoy unlimited, unstructured authority, to arrest and detain suspects. For example, Section 167 (1) Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) stipulates that a suspect has to be presented before a magistrate within 24 hours of arrest and Section 167 (2) specifies that physical remand for up to 15 days can be obtained from the magistrate.

The police abuse their powers by not bringing the suspects before the magistrate within the stipulated period and the arrest is not even declared for days. Even after obtaining physical remand, the police resort to torture with impunity. In the police stations of Punjab, CCTV cameras were installed to keep an eye on police officials so that they could not abuse their powers. To avoid being found out, the police set up their own private detention centres in hired buildings. Amjad was kept and tortured in one such private torture cell. All senior police officers are aware of this but do not raise any objections because this is the only method of investigating the accused that they know. Whenever there is a crime, interrogation and investigation usually mean nabbing all persons concerned and subjecting them to torture in the hope that someone will reveal the real story. Police are often under-resourced and ill-equipped to deal with the challenges of modern policing and investigation.

Importantly, a lack of accountability for police excesses has encouraged a culture of impunity among the force. In the old system introduced by the British Raj, the police operated under the supervision and administrative control of the deputy commissioner, who would keep a check on any abuse of power. However, gradually the police managed to free themselves of the deputy commissioner’s supervision by serving the political elite who amended the law for this purpose. In the 2002 Police Order, two institutions, the Police Complaint Authority and the Public Safety Commissions, were envisaged to work as a check on the police, but the politicians and the police bureaucracy worked in tandem to frustrate this scheme and did not allow the setting up of any institutional supervisory mechanism. Consequently, the police are neither answerable to the deputy commissioners nor the new institutions envisaged for this purpose.

Another major issue is that Pakistan lacks a comprehensive legislation to prevent and criminalise police torture. On the issue of custodial deaths, the Criminal Procedure Code Section 176 CrPC mandates a magisterial inquiry in all cases of custodial deaths but such inquiries are conducted to whitewash a crime. Further, while FIRs are registered against police officers accused of torture and murder, they rarely result in any convictions, as the police investigations in most cases try to save the skin of their colleagues. The police force needs to be modernised, and police officials involved in custodial deaths and other human rights’ violations should be held accountable through a transparent and efficient mechanism.

Ideally, the state needs to criminalise crimes by the police against the accused in their custody by tightening the existing laws and providing a mechanism whereby they ensure that custodial crimes do not go unpunished. The law needs to clearly state that if there is evidence that injury to a person was caused in police custody, the court shall presume that the injury was caused by the police, unless proven to the contrary. The frailty of a victim should not be used as a defence. Further, there is need to limit the unregulated powers of the police to arrest, detain and interrogate by providing statutory guidelines.

Earlier this year, when the Punjab police killed several members of the same family near Sahiwal on suspicion of terrorism, Prime Minister Imran Khan condemned the killings and promised to review the entire structure of the Punjab police and start the process of reforming it. However, like so many of his other promises, this one, too, has long been forgotten.