Death by Destruction

By Sohema Rehan | Life Style | Published 15 years ago

Like all children, I have vivid recollections of anecdotes recounted by my mother. She loves talking about her own childhood, and we have always hung on to every word of hers. She often speaks with awe of her paternal uncle, a senior police officer who “ruled the small, sleepy city of Hyderabad with an iron fist.” Public transporters would never charge a guest being dropped to his house and vendors would remain a lane away lest they got on the wrong side of his, or for that matter, any other member of his coveted family. Respect for him bordered on fear: most people plainly preferred to stay at arm’s length. The entire clan’s life simply revolved around his personality, likes and dislikes.

But this is not how I remember Chacha Ji. The man I know can only be described as a grown-up baby. His eyes always had a cloudy, wandering expression and his speech was disjointed and detached from the reality surrounding him. The doors of his house were strictly guarded and tightly locked, lest he wandered out unsupervised.

This is the reality of a person struck by Alzheimer’s — the behaviour of a disease which attacks the human brain, profoundly altering individuals. It steals away the most basic functions and fundamental pleasures, and the victims regress into a state of pathological dependency that is physically and emotionally draining not just for patients, but also their dear ones.

In the past, memory loss was believed to be a normal part of aging, but experts now recognise severe memory loss as a symptom of a serious illness. Many people feel that their memory becomes less sharp as they grow older, but determining whether there is any scientific basis for this belief is a research challenge still being addressed globally. The US government spends $338 million on research and the UK $29.2 million. According to newspaper statistics attributed to the Lahore-based Alzheimer’s Society of Pakistan, there are currently a million people living with Alzheimer’s and dementia in the country. However, repeated telephone calls and email messages byNewsline failed to elicit any response from the society.

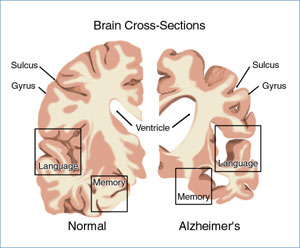

It is a scientifically accepted fact that Alzheimer’s is one of the more poorly understood diseases. The genetic component for family inheritance is rare and the disease is marked by dramatic shrinkage of the brain, especially of the cortex, the outer layer involved in memory, thinking, judgment and speech. It is a progressive disease that has no survivors. A microscopic evaluation shows widespread fatty deposits in small blood vessels, dead and dying brain cells, and abnormal deposits in and around cells. This, slowly and painfully, causes memory changes, erratic behaviour and loss of bodily functions, taking away a person’s identity, ability to connect with others, think, eat, talk, walk or function normally.

It is a scientifically accepted fact that Alzheimer’s is one of the more poorly understood diseases. The genetic component for family inheritance is rare and the disease is marked by dramatic shrinkage of the brain, especially of the cortex, the outer layer involved in memory, thinking, judgment and speech. It is a progressive disease that has no survivors. A microscopic evaluation shows widespread fatty deposits in small blood vessels, dead and dying brain cells, and abnormal deposits in and around cells. This, slowly and painfully, causes memory changes, erratic behaviour and loss of bodily functions, taking away a person’s identity, ability to connect with others, think, eat, talk, walk or function normally.

“My mother, Mrs Saeed, was the strength of our family, a hard-working librarian all her life who moved to the US in her mid-40s, only for better career prospects for my then teenage brother. Even there, she worked at various jobs and was eventually promoted to store manager at a leading retail store,” reveals a sad Yasmeen, a housewife suffering from severe osteoporosis, who lives in a two-bedroom apartment in a mid-income Karachi locality. Saeed was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the US that left her dependent, ill and regressing badly in the home of her only son, who was married to an American. As her condition worsened, Saeed’s son felt he was unable to care for his mother and brought her to Pakistan to be with his sister Yasmeen. In spite of her meagre means, Yasmeen has struggled hard to be the ideal caregiver for her mother, whose condition has only worsened since her return to the country. “For me, the most horrible moment was probably to find her sitting on the bathroom floor, smearing her body waste all over herself and attempting to devour it.” The old lady suffered a major stroke two years ago that has left her completely bed-ridden, unable to speak, eat or function normally. In the tiny fourth floor apartment, the sickly creature lies in the centre of Yasmeen’s bedroom, groaning and screaming away in agony, dealing with multiple infections and diseases and with feeding, breathing and urinary tubes attached to her frail body.

Primarily because of less emphasis on the health of older adults and fewer resources for health research compared with the industrialised nations, developing countries have not been able to report reliable prevalence data on age-related disorders such as dementia. Thus, the extent of the public health burden currently posed by Alzheimer’s and other dementias in developing countries remains an open question. Seniors, who quickly shed pounds, are at a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s, according to Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology. Earlier studies have shown that weight loss may precede the onset of Alzheimer’s by 10 to 20 years, suggesting that the disease may have a long latency period during which subtle changes like weight loss or minor memory problems may occur. Paradoxically, those who are obese or who have other risk factors for heart disease during midlife may be at increased risk for Alzheimer’s during their late years. At this time, there is no treatment to cure, delay or stop the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. FDA-approved drugs temporarily slow down the deterioration for about six to 12 months on average for about half of the individuals who take them.

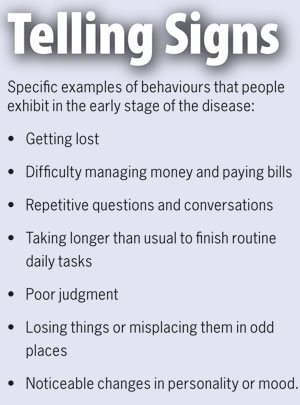

Patients typically have trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships. For some people, having vision problems is a sign of Alzheimer’s. They may have difficulty reading, judging distance and determining colour or contrast. In terms of perception, they may pass a mirror and think someone else is in the room. They may not recognise their own reflection. People with Alzheimer’s may have trouble following or joining in a conversation. They may stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue or they may repeat themselves. They may struggle with vocabulary, have problems finding the right word or identify objects by the wrong name (e.g., call a “watch” a “hand-clock).” Some common early symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease include confusion, disturbances in short-term memory, problems with attention and spatial orientation, changes in personality, language difficulties and unexplained mood swings. Normally, these symptoms are very mild and the presence of the disease may not be apparent to the person experiencing the symptoms, loved ones or even health professionals. Symptoms likely vary in severity and chronology, overlap and fluctuate and the overall progress of the disease is fairly predictable. On average, people live for eight to 10 years after diagnosis, but this terminal disease can last for as long as 20 years.

Patients typically have trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships. For some people, having vision problems is a sign of Alzheimer’s. They may have difficulty reading, judging distance and determining colour or contrast. In terms of perception, they may pass a mirror and think someone else is in the room. They may not recognise their own reflection. People with Alzheimer’s may have trouble following or joining in a conversation. They may stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue or they may repeat themselves. They may struggle with vocabulary, have problems finding the right word or identify objects by the wrong name (e.g., call a “watch” a “hand-clock).” Some common early symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease include confusion, disturbances in short-term memory, problems with attention and spatial orientation, changes in personality, language difficulties and unexplained mood swings. Normally, these symptoms are very mild and the presence of the disease may not be apparent to the person experiencing the symptoms, loved ones or even health professionals. Symptoms likely vary in severity and chronology, overlap and fluctuate and the overall progress of the disease is fairly predictable. On average, people live for eight to 10 years after diagnosis, but this terminal disease can last for as long as 20 years.

See related articles:

- Interview: Dr Saad Shafqat

- A caregiver’s account: “Eventually, we had to spoonfeed, groom and dress him ourselves”