A Year of Upheaval

By Deneb Sumbul | News & Politics | Published 10 years ago

Pakistan remained on the international radar in 2015 – for reasons more foul than fair.

By Deneb Sumbul

The Hangman’s Noose

January 15 saw the first executions of 2015 in Pakistan, with the hanging of Saeed Awan and Zahid Ali for the murders of police officers and civilians. After 2008, there was a six-year moratorium on the death penalty in the country. But after the Taliban attack on the Army Public School and Degree College, Peshawar, on 16 December 2014, in which 132 students and nine staff members were massacred, the moratorium was lifted as part of the revitalised crackdown on terrorism. According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), Pakistan has executed 329 death row prisoners between December 2014 and December 2015.

Death row inmate, Saulat Mirza, a die-hard political worker for the MQM, finally faced the gallows on March 19. Associated with the party since his student days at the Karachi University, Mirza allegedly went on to become one of the MQM’s most lethal assassins. He was accused of several hits, including the triple murders of Shahid Hamid (the then Managing Director of KESC), his bodyguard and driver, and in 1999 an anti-terrorism court awarded him the death sentence. His family’s repeated appeals for clemency to the Sindh High Court, the Supreme Court and finally to the President of Pakistan, were all rejected. Just before his execution in Balochistan’s Macch Central Jail, a video was leaked to the TV channels in which Saulat Mirza confessed to his crimes, saying they were committed on the directives of his party. Until his death, his family claimed he remained in contact with Altaf Hussain. The MQM, however, denied all such allegations and called Mirza’s confessions a conspiracy against them.

The Buck Stops Here

Ayyan Ali, a local fashion-world celebrity, hit the national headlines on March 14, when the Islamabad Airport Security Force stopped her just as she was about to board a flight to the UAE. A whopping $506,800 in cash was discovered from her personal baggage — $494,000 in excess of the legal limit of $10,000 that Pakistanis can carry out of Pakistan. Thereafter Ali was arrested for money-laundering and sent for a 14-day judicial remand, that kept getting extended. In each of her court appearances, there was Ali, attired in trendy apparel, sporting equally trendy shades and hairdos, accompanied by mysterious armed bodyguards in dark glasses. In the process the “supermodel,” hitherto known only in the fashion circuit, gained national fame/notoriety. Her high-profile defending council also generated particular interest: ex-governor of Punjab, former attorney general of Pakistan and ex-PPP senator, Latif Khosa. No surprises then, that rumours of the ostensibly apolitical Ali’s close ties to the PPP supremo began to whirl. While Ayyan was still behind bars, the customs officer who had confiscated her dollars — Chaudhry Ijaz, the key witness in the case — was shot by two armed motorcyclists. He died of his injuries in the hospital. The money confiscated from Ayyan at the airport was in his custody.

Ayyan Ali, a local fashion-world celebrity, hit the national headlines on March 14, when the Islamabad Airport Security Force stopped her just as she was about to board a flight to the UAE. A whopping $506,800 in cash was discovered from her personal baggage — $494,000 in excess of the legal limit of $10,000 that Pakistanis can carry out of Pakistan. Thereafter Ali was arrested for money-laundering and sent for a 14-day judicial remand, that kept getting extended. In each of her court appearances, there was Ali, attired in trendy apparel, sporting equally trendy shades and hairdos, accompanied by mysterious armed bodyguards in dark glasses. In the process the “supermodel,” hitherto known only in the fashion circuit, gained national fame/notoriety. Her high-profile defending council also generated particular interest: ex-governor of Punjab, former attorney general of Pakistan and ex-PPP senator, Latif Khosa. No surprises then, that rumours of the ostensibly apolitical Ali’s close ties to the PPP supremo began to whirl. While Ayyan was still behind bars, the customs officer who had confiscated her dollars — Chaudhry Ijaz, the key witness in the case — was shot by two armed motorcyclists. He died of his injuries in the hospital. The money confiscated from Ayyan at the airport was in his custody.

Ali was eventually released from jail on July 16, but not before she accused several other models and politicians of involvement in similar money-laundering. Ali has still not been charged or cleared, and the case against her continues, even as her name has been placed on the Exit Control List.

Truly Special

In early August, it was Pakistan’s special children that made the nation proud by bringing home a rich haul of 13 gold, 12 silver and 10 bronze medals earned at the 2015 Los Angeles Special Olympics. This year, at one of the biggest sporting events in the world for those with intellectual disabilities, LA was host to 7,000 athletes from 177 countries. The contingent from Pakistan consisted of a 55-member team of 43 males and 12 females. Before departing for the games, the country’s special athletes went through challenging training regimens in five training camps held over six months, across the country’s major cities. The training also included mentally preparing the athletes for being away from their homes and families for the first time – albeit accompanied by a team of support staff. Winning 35 medals in eight disciplines, the special Olympians returned home as heroes.

In early August, it was Pakistan’s special children that made the nation proud by bringing home a rich haul of 13 gold, 12 silver and 10 bronze medals earned at the 2015 Los Angeles Special Olympics. This year, at one of the biggest sporting events in the world for those with intellectual disabilities, LA was host to 7,000 athletes from 177 countries. The contingent from Pakistan consisted of a 55-member team of 43 males and 12 females. Before departing for the games, the country’s special athletes went through challenging training regimens in five training camps held over six months, across the country’s major cities. The training also included mentally preparing the athletes for being away from their homes and families for the first time – albeit accompanied by a team of support staff. Winning 35 medals in eight disciplines, the special Olympians returned home as heroes.

Murders Most Foul

Karachi’s civil society reverberated on April 24 night with the  shocking news of the targeted shooting and death of Sabeen Mahmud. The activist and leading light of the T2F — the heart and soul of Karachi’s new age tea-house culture — was taken down by unidentified gunmen as she was returning home from an event at the T2F with her mother, who was also wounded in the attack. Subsequently, Mahmud’s driver, the lone witness to the execution, was also shot dead by unidentified assailants. Accompanying the shock and outrage engendered by the horrific killing, conjecture about the motives behind it ran rife. Mahmud had just hosted a seminar at the T2F titled ‘Unsilencing Balochistan (Take 2)’ — a taboo subject which had earlier been scheduled at — and then cancelled — by the prestigious LUMs. One of the speakers at the seminar was Mama Qadeer, a Baloch activist and spokesperson for missing persons in Balochistan. Mahmud’s murder was widely condemned and placed under the Terrorism Act. On May 20, Sindh Chief Minister, Qaim Ali Shah stated that the mastermind behind Sabeen Mahmud’s assassination was Saad Aziz, who was not only a regular T2F visitor, but also an IBA graduate. Later, he confessed to his involvement in the Safoora Goth bus shooting against the Ismailis as well.

shocking news of the targeted shooting and death of Sabeen Mahmud. The activist and leading light of the T2F — the heart and soul of Karachi’s new age tea-house culture — was taken down by unidentified gunmen as she was returning home from an event at the T2F with her mother, who was also wounded in the attack. Subsequently, Mahmud’s driver, the lone witness to the execution, was also shot dead by unidentified assailants. Accompanying the shock and outrage engendered by the horrific killing, conjecture about the motives behind it ran rife. Mahmud had just hosted a seminar at the T2F titled ‘Unsilencing Balochistan (Take 2)’ — a taboo subject which had earlier been scheduled at — and then cancelled — by the prestigious LUMs. One of the speakers at the seminar was Mama Qadeer, a Baloch activist and spokesperson for missing persons in Balochistan. Mahmud’s murder was widely condemned and placed under the Terrorism Act. On May 20, Sindh Chief Minister, Qaim Ali Shah stated that the mastermind behind Sabeen Mahmud’s assassination was Saad Aziz, who was not only a regular T2F visitor, but also an IBA graduate. Later, he confessed to his involvement in the Safoora Goth bus shooting against the Ismailis as well.

In mid August, the dynamic Punjab interior minister and ex-army officer, Shuja Khanzada was killed in a suicide attack along with 22 people while he held a meeting at his political office in Attock. Khanzada had built a reputation for fearlessly spearheading campaigns against terrorism and militant groups in the Punjab. The brutal sectarian outfit, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) claimed responsibility for his assassination, and said it was in retaliation for the killing of their co-founder and leader, Malik Ishaq on July 29. Terror linchpin Ishaq was said to have been killed along with his two sons and 11 others, including his second-in-command, in an encounter with the counter-terrorism department of the Punjab police. During Ishaq’s leadership of the LeJ, there were several targeted mass-killings, mostly of members of the Shia and Barelvi community. The LeJ had also claimed responsibility for the attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team in Lahore in 2009, the Ashura bombings in Afghanistan in 2011, and the 2013 bombings that killed 200 Hazara Shias in Quetta. Ishaq alone had been charged in more than 100 murder and 45 criminal cases.

In mid August, the dynamic Punjab interior minister and ex-army officer, Shuja Khanzada was killed in a suicide attack along with 22 people while he held a meeting at his political office in Attock. Khanzada had built a reputation for fearlessly spearheading campaigns against terrorism and militant groups in the Punjab. The brutal sectarian outfit, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) claimed responsibility for his assassination, and said it was in retaliation for the killing of their co-founder and leader, Malik Ishaq on July 29. Terror linchpin Ishaq was said to have been killed along with his two sons and 11 others, including his second-in-command, in an encounter with the counter-terrorism department of the Punjab police. During Ishaq’s leadership of the LeJ, there were several targeted mass-killings, mostly of members of the Shia and Barelvi community. The LeJ had also claimed responsibility for the attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team in Lahore in 2009, the Ashura bombings in Afghanistan in 2011, and the 2013 bombings that killed 200 Hazara Shias in Quetta. Ishaq alone had been charged in more than 100 murder and 45 criminal cases.

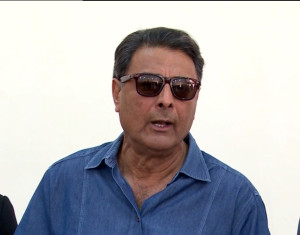

MQM leader Rashid Godail, miraculously survived an assassination attempt on August 18 while travelling with his  family. Unknown gunmen stopped his car and after identifying him, pumped eight bullets into him that ripped open his chest, arm and head. He lived to tell the tale, but his driver died on the spot.

family. Unknown gunmen stopped his car and after identifying him, pumped eight bullets into him that ripped open his chest, arm and head. He lived to tell the tale, but his driver died on the spot.

Karachi faced another tragedy on May 13 when a bus full of commuters en route from Safoora Goth, the city’s periphery, was stopped and attacked by six gunmen. The perpetrators boarded the bus and opened fire at point-blank range, cutting short the lives of 45 passengers, including 17 women — all of whom died of shots to the head. The victims were residents of Al Azhar Gardens, who regularly travelled via bus to their various destinations and most belonged to the Ismaili community. Eight passengers survived and were shifted to the nearest hospital in critical condition. The brutal killing came to be known as the Safoora Goth carnage, and the city mourned as the Prime Minister announced the national flag would be flown at half-mast the next day. Following the attack, the city’s law-enforcement agencies collectively decided to intensify targeted operations against terrorist elements in Karachi. Three days later, apart from Saad Aziz — the main accused  in Sabeen Mahmud’s murder, who had also confessed to complicity in the Safoora carnage — the government arrested Tahir Hussain Minhas, the other mastermind behind the attack, along with Mohammad Azhar Irshad and Hafiz Nasir. All four were educated and each had a long history of involvement in terrorist activity and were skilled in bomb-making. Subsequent reports stated that pro-IS leaflets were found near the scene of the carnage. And recent investigations lent strength to IS links when a strong women’s wing network was discovered, operated by the wives of Saad Aziz and the other key suspects, who were engaged in raising funds through donations for their husbands’ IS-inspired activites.

in Sabeen Mahmud’s murder, who had also confessed to complicity in the Safoora carnage — the government arrested Tahir Hussain Minhas, the other mastermind behind the attack, along with Mohammad Azhar Irshad and Hafiz Nasir. All four were educated and each had a long history of involvement in terrorist activity and were skilled in bomb-making. Subsequent reports stated that pro-IS leaflets were found near the scene of the carnage. And recent investigations lent strength to IS links when a strong women’s wing network was discovered, operated by the wives of Saad Aziz and the other key suspects, who were engaged in raising funds through donations for their husbands’ IS-inspired activites.

Heat and Dust

Around mid-June, during the month of Ramzan, an  unprecedented heat wave — the worst since 1979 — struck the southern part of the country, with temperatures as high as 49 °C (120 °F). The week-long, extreme weather caused the deaths of more than 1400 people from heat-stroke and dehydration. Most casualties in Sindh were from the mega city of Karachi, which also suffered acute water shortages during that time, as well as a collapsed power grid leaving thousands without electricity in a city already facing frequent load-shedding. Health and emergency facilities were so stretched that the Sindh Rangers had to establish heat-stroke centres across Karachi. More than 65,000 people flooded government and private hospitals, where 40,000 alone were treated for heat-stroke. City morgues became overwhelmed as bodies had to be piled one on top of another. The Edhi Foundation held a mass burial at a graveyard in Karachi, as most of those who were affected were the poor, the elderly and the unclaimed — and quick burials became a necessity. The intense heat-wave also claimed the lives of countless livestock. In a complete departure from the exhortations from the local clergy in recent times, for the first time some religious leaders actually encouraged people to either break their fasts early if they felt unwell, or avoid fasting altogether during the soaring temperatures. As always in times of natural disasters, dissatisfied with the provincial government’s response to the crisis, Karachi civil society sprang into action, with volunteers distributing water, ice and iftari on the streets and getting medical supplies to hospitals and clinics in need.

unprecedented heat wave — the worst since 1979 — struck the southern part of the country, with temperatures as high as 49 °C (120 °F). The week-long, extreme weather caused the deaths of more than 1400 people from heat-stroke and dehydration. Most casualties in Sindh were from the mega city of Karachi, which also suffered acute water shortages during that time, as well as a collapsed power grid leaving thousands without electricity in a city already facing frequent load-shedding. Health and emergency facilities were so stretched that the Sindh Rangers had to establish heat-stroke centres across Karachi. More than 65,000 people flooded government and private hospitals, where 40,000 alone were treated for heat-stroke. City morgues became overwhelmed as bodies had to be piled one on top of another. The Edhi Foundation held a mass burial at a graveyard in Karachi, as most of those who were affected were the poor, the elderly and the unclaimed — and quick burials became a necessity. The intense heat-wave also claimed the lives of countless livestock. In a complete departure from the exhortations from the local clergy in recent times, for the first time some religious leaders actually encouraged people to either break their fasts early if they felt unwell, or avoid fasting altogether during the soaring temperatures. As always in times of natural disasters, dissatisfied with the provincial government’s response to the crisis, Karachi civil society sprang into action, with volunteers distributing water, ice and iftari on the streets and getting medical supplies to hospitals and clinics in need.

Crime and Punishment

In July, one of the most shameful episodes in the country’s history hit the headlines, as a huge child abuse scandal surfaced in Kasur, a district of the Punjab. A child pornography ring, operating with complete impunity for more than eight years, was unveiled, but only after hundreds of children and youngsters had been raped and sodomised in the traumatised village of Hussain Khanwa. To add insult to injury, the paedophiles videotaped these sordid sexual crimes and then proceeded to blackmail the parents of the children, demanding money in exchange for their silence. And for eight long years, the parents of the victims, in the conservative backwater of Kasur, were silent — out of shame. But when the story broke, more than 400 videos of 284 children being assaulted by 25 assailants and their abettors surfaced. It was learnt that a photo studio, owned by one of the suspects, sold the videos for Rs. 50 per CD.

In July, one of the most shameful episodes in the country’s history hit the headlines, as a huge child abuse scandal surfaced in Kasur, a district of the Punjab. A child pornography ring, operating with complete impunity for more than eight years, was unveiled, but only after hundreds of children and youngsters had been raped and sodomised in the traumatised village of Hussain Khanwa. To add insult to injury, the paedophiles videotaped these sordid sexual crimes and then proceeded to blackmail the parents of the children, demanding money in exchange for their silence. And for eight long years, the parents of the victims, in the conservative backwater of Kasur, were silent — out of shame. But when the story broke, more than 400 videos of 284 children being assaulted by 25 assailants and their abettors surfaced. It was learnt that a photo studio, owned by one of the suspects, sold the videos for Rs. 50 per CD.

Some of the victims’ parents claimed they had been trying to file reports of the rapes perpetrated on their young children for years but were unable to do so due to the reluctance of the police to take action. In fact, the police manufactured elaborate cover-ups, and worse, harassed the complainants by implicating them in false criminal cases. The affected parents contended that the police response was almost as bad a crime as the rapes, since their inertia allowed the bestiality to continue. They only sprang to action after intense media pressure, and that owed to the fact that the villagers continued protesting for four months. The provincial authorities, including Punjab Senior Minister, Rana Sanaullah, meanwhile, tried to give it a different spin, calling the matter a land dispute, and vehemently denying any child abuse had ever occurred. This led outraged villagers to clash with the police and once the media heard of it, there was a national outcry. Eventually 22 FIRs were registered against the culprits of what the head of the Child Protection and Welfare Bureau called “the largest-ever child abuse scandal in Pakistan’s history.” The total number of victims is still unknown. The only silver lining to this cloud is that it has encouraged victims in other parts of the country to speak up about a subject once considered taboo.

Tectonic Tragedy

A 7.5 magnitude earthquake violently jolted major cities of northern Pakistan in the afternoon of October 26. This was followed by a 4.8 magnitude aftershock in the same area 40 minutes later. Although the epicentre was in the Hindu Kush range in Afghanistan, the tremors were felt as far away as Karachi and Delhi. The preliminary death toll tally in the region was reported at 248, but later it was estimated to be as high as 380. Many of the deaths and injuries were caused by collapsed buildings and structures and according to the National Disaster Management Authority, 109,110 homes were damaged over a wide swathe of the mountainous terrain, of which 29,228 were completely reduced to rubble. One of the strongest quakes in the last 10 years, it caused landslides and crippled communication lines, delaying rescue and relief efforts to reach the remote, mountainous parts that had suffered the worst effects of the quake. Till help finally arrived, people were left exposed to the elements without any resources. Earthquake affectees chose to spend the nights outdoors in the freezing weather for fear of aftershocks. An ominous portent: a recent report by the US Geological Survey stated that Pakistan is located on a quake zone with one of the world’s highest seismic activity rates and all the quakes in recent years have been a result of the convergence between the South Asian and Eurasian tectonic plates.

A 7.5 magnitude earthquake violently jolted major cities of northern Pakistan in the afternoon of October 26. This was followed by a 4.8 magnitude aftershock in the same area 40 minutes later. Although the epicentre was in the Hindu Kush range in Afghanistan, the tremors were felt as far away as Karachi and Delhi. The preliminary death toll tally in the region was reported at 248, but later it was estimated to be as high as 380. Many of the deaths and injuries were caused by collapsed buildings and structures and according to the National Disaster Management Authority, 109,110 homes were damaged over a wide swathe of the mountainous terrain, of which 29,228 were completely reduced to rubble. One of the strongest quakes in the last 10 years, it caused landslides and crippled communication lines, delaying rescue and relief efforts to reach the remote, mountainous parts that had suffered the worst effects of the quake. Till help finally arrived, people were left exposed to the elements without any resources. Earthquake affectees chose to spend the nights outdoors in the freezing weather for fear of aftershocks. An ominous portent: a recent report by the US Geological Survey stated that Pakistan is located on a quake zone with one of the world’s highest seismic activity rates and all the quakes in recent years have been a result of the convergence between the South Asian and Eurasian tectonic plates.

Deadly Blades

A bizarre air crash on May 8, involved an army helicopter carrying a delegation of foreign dignitaries. The craft literally fell out of the sky and crashed at a local school — both going up in flames. Mercifully, the school was closed at the time, but of the 17 passengers on board the Mi17 helicopter, seven passengers were killed: the ambassadors of Norway and the Philippines, the wives of the Malaysian and Indonesian ambassadors, two pilots and a crew member. The injured, including the Polish and Dutch ambassadors, were airlifted to the nearby Combined Military Hospital. The envoys — a large group from 37 countries — were being taken to the inaugural ceremony of a ski resort chairlift, which Prime Minster Nawaz Sharif was also to attend. The government had also organised a three-day tour of Gilgit for all the diplomats and their spouses, and the ambassadors were expected to hold high-level meetings with the Gilgit-Baltistan chief minister.

A bizarre air crash on May 8, involved an army helicopter carrying a delegation of foreign dignitaries. The craft literally fell out of the sky and crashed at a local school — both going up in flames. Mercifully, the school was closed at the time, but of the 17 passengers on board the Mi17 helicopter, seven passengers were killed: the ambassadors of Norway and the Philippines, the wives of the Malaysian and Indonesian ambassadors, two pilots and a crew member. The injured, including the Polish and Dutch ambassadors, were airlifted to the nearby Combined Military Hospital. The envoys — a large group from 37 countries — were being taken to the inaugural ceremony of a ski resort chairlift, which Prime Minster Nawaz Sharif was also to attend. The government had also organised a three-day tour of Gilgit for all the diplomats and their spouses, and the ambassadors were expected to hold high-level meetings with the Gilgit-Baltistan chief minister.

There are conflicting accounts as to the cause of the crash. The Pakistani Taliban took credit for downing the helicopter, but the defence ministry refuted the claim saying there was no evidence of any firing at the aircraft. They maintained it was due to a technical fault. Some eye-witnesses said they saw the helicopter catch fire before crashing; others said it burst into flames after it plummeted to the ground. Some eyewitness accounts report that there were strong gusts of wind that might have caused the helicopter to suddenly start spinning out of control. In recent years, the Russian-built Mi-17, used by air forces across the world, has had a patchy safety record.

On November 4, another horrific accident occurred: a factory collapsed at the Sandar Industrial Estate (SIE) in Lahore. The massive structure caved in during ongoing construction on the third storey of the building, killing at least 46 and trapping over a 100 workers, including factory owner, Rana Ashraf. Investigations revealed that among the reasons for the collapse were the absence of the necessary pillars and structures to support the edifice, in addition to a long list detailing official negligence and inaction. In its findings, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) stated that the disaster could have been prevented had regulations and restrictions regarding the construction of such structures been followed by the administration. The construction had been approved by the SIE board. Other glaring irregularities were that the polythene factory employed workers at half the minimum wage. According to the HRCP report, many of the employees at the factory were children working under very hazardous conditions. The joint rescue operations conducted by the civil administration, police, Rescue 1122 and the army, included the use of sniffer dogs, resolution cameras and trained personnel to locate those trapped. Due to their efforts 17,000 tonnes of debris were moved using heavy machinery and 103 injured individuals and 45 bodies were pulled out from under the rubble. They also used sniffer dogs, high resolution cameras and trained personnel for locating those trapped. The HRCP report concluded that in the last couple of years numerous lives have been lost in a similar manner because business and factory owners compromise workers’ safety to maximise their profits.

On November 4, another horrific accident occurred: a factory collapsed at the Sandar Industrial Estate (SIE) in Lahore. The massive structure caved in during ongoing construction on the third storey of the building, killing at least 46 and trapping over a 100 workers, including factory owner, Rana Ashraf. Investigations revealed that among the reasons for the collapse were the absence of the necessary pillars and structures to support the edifice, in addition to a long list detailing official negligence and inaction. In its findings, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) stated that the disaster could have been prevented had regulations and restrictions regarding the construction of such structures been followed by the administration. The construction had been approved by the SIE board. Other glaring irregularities were that the polythene factory employed workers at half the minimum wage. According to the HRCP report, many of the employees at the factory were children working under very hazardous conditions. The joint rescue operations conducted by the civil administration, police, Rescue 1122 and the army, included the use of sniffer dogs, resolution cameras and trained personnel to locate those trapped. Due to their efforts 17,000 tonnes of debris were moved using heavy machinery and 103 injured individuals and 45 bodies were pulled out from under the rubble. They also used sniffer dogs, high resolution cameras and trained personnel for locating those trapped. The HRCP report concluded that in the last couple of years numerous lives have been lost in a similar manner because business and factory owners compromise workers’ safety to maximise their profits.

Return of the Rain

Weeks of continuous rain in July resulted in flash floods in the Kunar or Chitral River, which devastated large swathes of the surrounding region, paralysing village life in many of the valleys. At least 600 homes were reportedly washed away in Chitral, Skardu, Gilgit and Ghanche by the unusually heavy torrential rains. Furthermore, unlike suspension bridges, the newer concrete ones were unable to withstand the force of the floods and were washed away, leaving villages completely cut off. The flash floods also innundated connective roads, decimated orchards; standing crops, hundreds of livestock and as many as nine hydel power houses. On July 20, 2015, soldiers from the Pakistan army began relief activities for the stranded affectees, distributing relief goods and food items.

Weeks of continuous rain in July resulted in flash floods in the Kunar or Chitral River, which devastated large swathes of the surrounding region, paralysing village life in many of the valleys. At least 600 homes were reportedly washed away in Chitral, Skardu, Gilgit and Ghanche by the unusually heavy torrential rains. Furthermore, unlike suspension bridges, the newer concrete ones were unable to withstand the force of the floods and were washed away, leaving villages completely cut off. The flash floods also innundated connective roads, decimated orchards; standing crops, hundreds of livestock and as many as nine hydel power houses. On July 20, 2015, soldiers from the Pakistan army began relief activities for the stranded affectees, distributing relief goods and food items.

Local residents point to distinct changes in the weather pattern as the cause of the unusually long spell of torrential rains that swelled the Chitral river system. Climate-change scientists have often maintained there is a close connection between the Asian monsoon system and the greenhouse effect, and now are certain that the monsoons are more susceptible to global climate change than earlier thought.

Act of Man?

Some of the tragedies of 2015 seemed more a result of human error than an act of God. On July 2, four carriages of a special military train carrying a unit of the Pakistan army derailed. As the train made its way on the Chanawan Bridge tracks, it collapsed, and one of the carriages ended up in the canal. Of the 300 passengers on board — all from the Pakistan army corps of engineers and their families — 19 were killed, and more than a 100 injured. Railways Minister, Khawaja Saad Rafique, initially attributed the accident to a possible terrorist attack, but a local police officer said the bridge was in poor condition and no explosives or devices were found at the site, thereby tacitly refuting Rafique’s claim. The minister responded by stating that all bridges were checked four times a year, and no faults were found with the Chanawan Bridge when it was checked in January.

Some of the tragedies of 2015 seemed more a result of human error than an act of God. On July 2, four carriages of a special military train carrying a unit of the Pakistan army derailed. As the train made its way on the Chanawan Bridge tracks, it collapsed, and one of the carriages ended up in the canal. Of the 300 passengers on board — all from the Pakistan army corps of engineers and their families — 19 were killed, and more than a 100 injured. Railways Minister, Khawaja Saad Rafique, initially attributed the accident to a possible terrorist attack, but a local police officer said the bridge was in poor condition and no explosives or devices were found at the site, thereby tacitly refuting Rafique’s claim. The minister responded by stating that all bridges were checked four times a year, and no faults were found with the Chanawan Bridge when it was checked in January.

Soon thereafter, however, a conflicting report emerged which stated the bridge was in an extremely precarious condition. Whatever the truth of the matter, a subsequent inquiry committee concluded that the train derailed before reaching the bridge because of a fault in the tracks, and an already weak bridge collapsed when the train crossed over it.

Minority Report

Two Christian churches in Lahore were targeted by suicide-bombers on March 15, killing 17 people while injuring at least 70 others. Had it not been for the sheer bravery of the volunteer security guards in blocking the perpetrators’ entry deeper into the church, the death toll would have been much higher. Outraged at their places of worship being attacked, the Christian community in Lahore came out in protest the next day. The demonstrations turned ugly when two Muslims got lynched. While the Christian community leaders strongly condemned the violent assaults, they also bemoaned how hundreds of members of their community were arbitrarily arrested and brutally beaten by the police in order to extract confessions. They also complained about police high-handedness and incidents of the extortion of money from poor Christians by these `law-enforcers.’

Two Christian churches in Lahore were targeted by suicide-bombers on March 15, killing 17 people while injuring at least 70 others. Had it not been for the sheer bravery of the volunteer security guards in blocking the perpetrators’ entry deeper into the church, the death toll would have been much higher. Outraged at their places of worship being attacked, the Christian community in Lahore came out in protest the next day. The demonstrations turned ugly when two Muslims got lynched. While the Christian community leaders strongly condemned the violent assaults, they also bemoaned how hundreds of members of their community were arbitrarily arrested and brutally beaten by the police in order to extract confessions. They also complained about police high-handedness and incidents of the extortion of money from poor Christians by these `law-enforcers.’

Understandably feeling vulnerable and terrified, during this time many families felt compelled to escape from Youhanabad, the largest Christian locality in Lahore, leaving their homes open to looting and occupation.

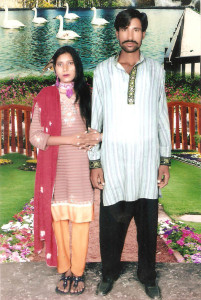

On November 4, a Christian couple from a town near Kot Radha Kishan in the Punjab had their legs broken by a frenzied mob, who then tossed them into an industrial brick kiln. The couple, Shahbaz Maseeh, 26 and his wife Shama Bibi, 24, worked in a clay factory. When Shama’s father died, she was burning several personal items she had gathered from his home thinking they were useless clutter, whereupon, a man, who presumably had a personal axe to grind, declared he had seen Shama burning pages of the Quran, and proceeded to spread the word. A mob from five villages consisting of hundreds of people, converged on the factory and locked the couple in the office on November 2. Two days later they were pushed into the  burning kiln. Human rights activist, Sardar Mushtaq Gill, was frantically summoned for help by local Christians who helplessly witnessed the mob’s inhumanity. It was too late. All he could do was alert the police who later arrested 35 suspects.

burning kiln. Human rights activist, Sardar Mushtaq Gill, was frantically summoned for help by local Christians who helplessly witnessed the mob’s inhumanity. It was too late. All he could do was alert the police who later arrested 35 suspects.

On November 20, a large chipboard factory in Jhelum, established in 1947 and owned by members of the Ahmedi community, was set ablaze by a violent crowd numbering several hundred. Accusing the factory administration of burning pages of the Quran, the horde had been largely incited by calls to jihad against blasphemy by the imams at local mosques. As a result, four employees had been arrested — and later released — which only angered the mob further. The police’s refusal to arrest the factory owner, set the mob on a rampage. They set fire to the plant, completely gutting it and looting the homes of the owner and management staff. Despite arriving late on the scene, the police made every attempt to stop the carnage, but even the local DPO got pelted with bricks while rescuing families from the uncontrollable mob. Thankfully, there were no casualties, but the next day another enraged crowd converged on a nearby Ahmedi mosque, breaking through police cordons in an attempt to set it ablaze as well. Only when the army was called to assist the police did the situation calm down.

In 2015, numerous targeted attacks on the members of the Hazara community in Balochistan, particularly in Quetta, fostered bitter feelings among them of abandonment by the government. Almost every month, from April till November, there were targeted killing of Hazaras. In April, at least two Hazara men were killed on a bus carrying pilgrims from Quetta to Taftan. Between May and June there was a wave of sectarian attacks on the Hazaras. In June, after five Hazara men were gunned down by militants near Bacha Khan Chowk, the city’s commercial hub, markets and businesses shut down as panic gripped the area. This was the fifth attack on Hazaras in Quetta within a span of two weeks. About 500 members of the Hazara community came out in protest, carrying coffins of their dead and placing them on the road, refusing to bury them till their protests were heard. While no outfit claimed responsibility for the attacks, the militant group Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) is considered the prime suspect.

In 2015, numerous targeted attacks on the members of the Hazara community in Balochistan, particularly in Quetta, fostered bitter feelings among them of abandonment by the government. Almost every month, from April till November, there were targeted killing of Hazaras. In April, at least two Hazara men were killed on a bus carrying pilgrims from Quetta to Taftan. Between May and June there was a wave of sectarian attacks on the Hazaras. In June, after five Hazara men were gunned down by militants near Bacha Khan Chowk, the city’s commercial hub, markets and businesses shut down as panic gripped the area. This was the fifth attack on Hazaras in Quetta within a span of two weeks. About 500 members of the Hazara community came out in protest, carrying coffins of their dead and placing them on the road, refusing to bury them till their protests were heard. While no outfit claimed responsibility for the attacks, the militant group Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) is considered the prime suspect.

The office of a Christian web TV channel, Gawahi.tv, was destroyed in a suspected arson attack in Karachi on November 26. Located in a three-room apartment in the Christian neighbourhood of Akhtar Colony, the Mehmoodabad police called Sarfaraz William in the middle of the night to inform him, that his studio was on fire. By the time the fire brigade had arrived, all equipment and materials had been burnt beyond repair. William informed the police that he had been receiving threats for the last six months by religious organisations demanding he shut his office down, or else.

This article was originally published in Newsline’s Annual 2016 issue.

The writer is working with the Newsline as Assistant Editor, she is a documentary filmmaker and activist.