Fallen Idol

By Zahid Hussain | News & Politics | Published 22 years ago

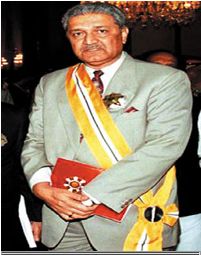

In his halcyon days, Abdul Qadeer Khan, now 69, was accustomed to adulation and worship. Credited with fathering the “first Islamic atom bomb,” Khan has, for decades, been publicly hailed as a national hero. His life-size portraits adorned the streets. People named their children after him. His motorcade used to be even larger than that afforded to the head of state. As a precious national asset, he was protected by military commandos. But even national heroes have their tragic flaws. The idol has now fallen from grace after his dramatic public confession of betraying the national trust by transferring nuclear technology to Libya, Iran and Korea.

In his halcyon days, Abdul Qadeer Khan, now 69, was accustomed to adulation and worship. Credited with fathering the “first Islamic atom bomb,” Khan has, for decades, been publicly hailed as a national hero. His life-size portraits adorned the streets. People named their children after him. His motorcade used to be even larger than that afforded to the head of state. As a precious national asset, he was protected by military commandos. But even national heroes have their tragic flaws. The idol has now fallen from grace after his dramatic public confession of betraying the national trust by transferring nuclear technology to Libya, Iran and Korea.

Khan played a key role in Pakistan’s nuclear weapons capability that culminated in successful tests in May 1998. Coming shortly after similar tests by arch rival India, the explosions established Pakistan as the world’s seventh nuclear power.

Born into a modest family in Bhopal, India, in 1935, Khan migrated to Pakistan in 1952. After graduating from Karachi University, he moved to Europe for higher studies in Germany and Belgium. In the 1970s, he took up a job at a uranium-enrichment plant run by the British-Dutch-German consortium, Urenco. There he met his Dutch wife, Hendrina.

He returned home in 1976 to head the nation’s nuclear programme, a position he held for 26 years. Khan Research Laboratories (KRL), named after Khan, became Pakistan’s main nuclear facility. The project is credited with ultimately leading to Pakistan’s first nuclear test explosion in May 1998.

His procurement of the secret centrifuge design from Urenco was critical to Pakistan’s successful nuclearisation. He was charged with stealing trade secrets and sentenced, in absentia, to a four-year prison term by a court in the Netherlands in 1983. The sentence was later quashed on appeal.

With unlimited government resources at his disposal that were free of auditing restrictions, Khan, a metallurgist who is often wrongly referred to as a nuclear scientist, managed to purchase restricted materials from European and American companies. In the process, he became a wealthy man.

He owns several palatial houses in Islamabad. In recent weeks, newspapers have reported that Khan had a vast array of real estate holdings in several foreign countries, including a hotel in Timbuktu, Mali. His fondness for vintage cars is evident from a huge fleet parked at one of his villas at the foot of Islamabad’s scenic Margalla hills.

Khan is known to have a megaton ego. Even when he was at the centre of investigations into his role in the most shocking nuclear proliferation scandal, he threw down the gauntlet by boasting in a television interview: “Who made the atom bomb? I made it. Who made the missiles? I made them for you.”

He recently told a news website: “I am proud of my work for my country. It has given Pakistan a sense of pride, security and has been a great scientific achievement.” His success made KRL, according to one analyst, “an unaccountable state within the larger unaccountable praetorian state of Pakistan.” Like a king he doled out money to build monuments and funded seminars that projected him as a “great Islamic hero.”

In later years, Mr Khan launched a campaign against illiteracy and built several educational institutes.

His aura began to diminish in March 2001 when President Musharraf, reportedly under US pressure, removed him from KRL. He continued to attract US suspicion and, in 2003, Washington imposed sanctions on the KRL for the alleged transfer of missile technology from North Korea.

Nevertheless, Pakistan’s nuclear establishment had never expected to see its most revered hero in the dock. The latest revelation about his dubious deals and extraordinary wealth may have dented his image, but he continues to remain popular among the common people who refuse to admit any flaw in their icon.

The writer is a senior journalist and author. He has been associated to the Newsline as senior editor at.