Flights of Fantasy

By Marjorie Husain | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 14 years ago

Saeed Akhtar exhibited his work after a gap of 11 years. And Lahore’s Ejaz Gallery drew a large audience of artists, friends and art enthusiasts to this celebratory occasion. The retro (in a sense) was accompanied by the launch of a beautiful monograph published by Topical Printers, featuring the artist’s work since the 1960s. The book itself, with text by Khalid Mahmood, was a work of art, exquisitely designed by his son, Usman Saeed.

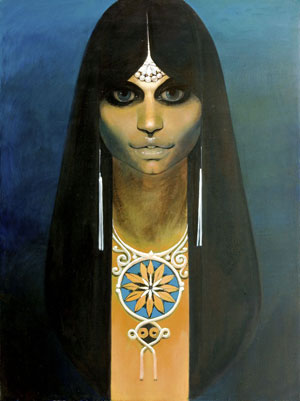

Filling two spacious halls of the Ejaz Gallery were large portraits, horses, the dazzling Buraq series (referred to by a TV presenter as Pegasus), and a series that combined brilliant draughtsmanship with fantasy, and consisting of beautiful, bejewelled, slender female figures, lightly clad. These were no earthly maidens; their world was exotic, bright with flowers, butterflies and birds. Though Akhtar had referred to the hues and jewels of Rajasthan in these works, the wide-eyed, gorgeous, slightly distorted creatures appeared to belong to another world.

Saeed Akhtar, who was born in Ghabar, near Gujranwala, in 1938, spent his formative years in Quetta, and it was here that he was first exposed to some paintings that hung in an officer’s mess — they were portraits of Rudyard Kipling and the Quaid-e-Azam painted by Hal Bevan Petman. An excellent draughtsman, Akhtar was impressed by the delicacy of Petman’s style, and wanted to take up the brush and canvas in earnest. But the only source of help available to him in those days were the billboard painters. Fortunately Akhtar’s father recognised his son’s talent and sent him to Lahore, where he applied to the National College of the Arts (NCA) for admission. Shakir Ali saw Akhtar’s drawings of the Quaid-e-Azam and his grandparents and asked, “If you can paint these so well, why have you come here?” To which Akhtar simply said, “Because I want to learn.”

Saeed Akhtar, who was born in Ghabar, near Gujranwala, in 1938, spent his formative years in Quetta, and it was here that he was first exposed to some paintings that hung in an officer’s mess — they were portraits of Rudyard Kipling and the Quaid-e-Azam painted by Hal Bevan Petman. An excellent draughtsman, Akhtar was impressed by the delicacy of Petman’s style, and wanted to take up the brush and canvas in earnest. But the only source of help available to him in those days were the billboard painters. Fortunately Akhtar’s father recognised his son’s talent and sent him to Lahore, where he applied to the National College of the Arts (NCA) for admission. Shakir Ali saw Akhtar’s drawings of the Quaid-e-Azam and his grandparents and asked, “If you can paint these so well, why have you come here?” To which Akhtar simply said, “Because I want to learn.”

The great master took him under his wings. Although the artist faced the challenge of colour-blindness initially, he soon overcame this problem and only after two years at the NCA, Shakir Ali offered him a part-time teaching post at the college alongside his studies. That was the beginning of a long, successful vocational career in art. In his fourth year at NCA, Akhtar focused on sculpture, a subject he was to teach for many years.

Akhtar studied abroad and travelled widely, received the President’s Pride of Performance in 1994, and was head of the fine arts department at NCA for 15 years.

The artist’s proficiency in portraiture dominated his output for a number of years; he painted numerous portraits of the Quaid-e-Azam and various heads of state. He secured his first private commission from a young woman who wanted a 6ft x 5ft painting of her father worked from a passport-type photograph. Akhtar found a suitable model to depict his full form.

Now that he has retired from NCA, Akhtar is a totally relaxed man: he spends the entire day working in his spacious studio in town. His day begins at 9:30 a.m. After dropping his grandchildren to school, he gets to work and winds up around 6 p.m. Though Akhtar has continued to paint portraits, he has finally found the time to fully explore other themes as well, perhaps for the first time. In fact, visitors at the incredible exhibition were stunned by the vibrant energy and movement of his Buraq series.

Among the 48 paintings on display were several self-portraits (in size 4ft x 4ft) of the artist in the costumes of the Baloch tribes he so admires. The other portraits, too, depicted men in huge turbans and women decked up in chunky jewellery. What struck the viewers were the large captivating eyes that dominated the canvases. The exhibit also included a beautiful study of the artist’s late wife, Sadia, and a painting which Akhtar had recently done as a gift for his grandchild. I witnessed several visitors approach the artist to acquire the painting but, in spite of their pleas, he explained politely that the painting was not for sale.

Among the 48 paintings on display were several self-portraits (in size 4ft x 4ft) of the artist in the costumes of the Baloch tribes he so admires. The other portraits, too, depicted men in huge turbans and women decked up in chunky jewellery. What struck the viewers were the large captivating eyes that dominated the canvases. The exhibit also included a beautiful study of the artist’s late wife, Sadia, and a painting which Akhtar had recently done as a gift for his grandchild. I witnessed several visitors approach the artist to acquire the painting but, in spite of their pleas, he explained politely that the painting was not for sale.

Ultimately, it was the Buraq series that bowled me over. A painting from the series was first exhibited at the PNCA National Exhibition held in Lahore, 2003.

The gorgeously winged horses appeared about to fly out of their frames. In the upper gallery, a friend and I were rendered speechless by a painting measuring 20ft x 6ft, in which, as we walked the length of the hall, the Buraq with wings of every hue in the rainbow and more, appeared to move with us, imperceptibly changing before our eyes. In the words of Mohammad Khalid Mahmud, author of Akhtar’s monograph, “The content of Akhtar’s art has always been aimed to put on view man’s quest for the Divine amidst sheer mortality.”