Tribute to a Master

By Niilofur Farrukh | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 20 years ago

Canvas cracks and tears disappear and paintings are re-stretched into shape in the skillful hands of Toronto’s much-respected restorer, Lazlo. In his studio, which houses art treasures from around the world, a drawing (circa 1960) is reclaimed from fragments found in the artist’s studio after his untimely death. Mounted on acid-free paper it is given a new life. Through this long and costly process the art of Zahoor ul Akhlaq is meticulously restored for his first international retrospective, ‘The Inner Sanctum, at Laal — the Passion of Zahoor ul Akhlaq,’ an exhibition that celebrates one of Pakistan’s most influential artist in recent times.

Canvas cracks and tears disappear and paintings are re-stretched into shape in the skillful hands of Toronto’s much-respected restorer, Lazlo. In his studio, which houses art treasures from around the world, a drawing (circa 1960) is reclaimed from fragments found in the artist’s studio after his untimely death. Mounted on acid-free paper it is given a new life. Through this long and costly process the art of Zahoor ul Akhlaq is meticulously restored for his first international retrospective, ‘The Inner Sanctum, at Laal — the Passion of Zahoor ul Akhlaq,’ an exhibition that celebrates one of Pakistan’s most influential artist in recent times.

The show resonated with the many dialogues started by the artist in his work and teaching career. In the Takhti Hall his engagement with fellow artists, both peers and former students, converged, as 80 works from the four corners of the globe became a dynamic symbol of this exchange. Inspired by the hand- held position of the takhti, which when in use is always tilted away from the student scribe, takhti paintings levitated on fine wires in perfect balance with their counterweights. This finely poised system ran along a central spine in the centre of the space and allowed each takhti to be appreciated separately. It also made the viewer aware that together these almost 80 pieces created a stunning visual symphony. The same is true of all art. Individually an artist brings a personal perspective, but the connectivity of these visual narratives makes it the repository of the history of a people, of a time.

The shared format of the takhti had allowed each artist to make it a point of departure. There was a textile-like quality in the mark-making techniques employed by Dorothy Caldwell which contrasted with Sylvat Aziz’s work that referenced the sensuous sheer and shimmer of dupattas from South Asia. A takhti was reclaimed by nature when the Mexican artist Agnes Olive meticulously masked it with natural-found material like seed pods, crisp membranes of leaves and twigs, a theme echoed by Amin Gulgee in his assemblage bronze leaves. Artists determined to impose a new hard form had reshaped the takhti into a flat fiddle and into ping pong racquets.

In an act as final as death, the takhti had been burnt in several works. Finland’s Maaria Wirkkala suggested alchemy as she had rubbed goldleaf over charred wood. ‘Acupuncture holes’ perforated the seared monochrome surface of Canadian Kai Chan’s work. When Eva Douglas (also from Canada) dropped her flaming takhti into molten glass the result was infinite fusion. The changing light helped the viewer to discover new patterns in this kaleidoscope of cinders trapped in the crystalline crevices of the glass block. Strangely reminiscent of a bird, Canadian Ryszhard Litwiniuk’s white piece focused on a convex shape projection on the horizontal takhti surface. Made out of recycled strips from the same semi-circular cut on which the half dome sat, it added yet another dimension to the wooden tablet.

In an act as final as death, the takhti had been burnt in several works. Finland’s Maaria Wirkkala suggested alchemy as she had rubbed goldleaf over charred wood. ‘Acupuncture holes’ perforated the seared monochrome surface of Canadian Kai Chan’s work. When Eva Douglas (also from Canada) dropped her flaming takhti into molten glass the result was infinite fusion. The changing light helped the viewer to discover new patterns in this kaleidoscope of cinders trapped in the crystalline crevices of the glass block. Strangely reminiscent of a bird, Canadian Ryszhard Litwiniuk’s white piece focused on a convex shape projection on the horizontal takhti surface. Made out of recycled strips from the same semi-circular cut on which the half dome sat, it added yet another dimension to the wooden tablet.

Artists in the show came from Indonesia, Turkey, Mexico, Sri lanka, Finland, Sweden, Bangladesh,Austria and USA, with the largest representation from Pakistan and Canada. From Pakistan were Colin David, Mehr Afroze, Akram Dost Baloch, Nazish Attaullah, Salima Hashmi, Jamal Shah, Anwer Saeed, Imran Qureshi, Shahzia Sikander and Risham Syed.

From the Takhti Hall the visitor entered a dimly lit alcove for respite. Curtained off, the intimate space here was reserved for the screening of ‘Flight,’ a short poignant film by Nurjehan, the film-maker daughter of Zahoor ul Akhlaq who shared the experience of her loss. The montage of images from Lahore and Zahoor’s art contextualised the life and death of the artist.

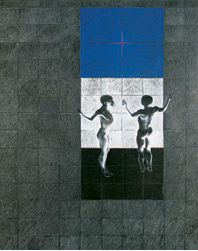

Beyond this threshold lay, ‘The Inner Sanctum.’ Enveloped in soft light that focused on the art, the room had a calming effect on the senses. The paintings that hung here were veterans of important shows like the prestigious Venice Biennale where his work was exhibited in 1997. Zahoor had the privilege to be the creator of the largest portrait of young Mohd. Ali Jinnah. This six foot by six foot portrait had pride of place in the show. Also on display were prints of the ‘Homage aux Prix Nobel’ series commissioned by Sweden’s Gallerie Borjeson soon after Pakistan’s Abdus Salam became a Nobel laureate. Nowhere was this sentiment more evident than in the content of his art that simultaneously chronicled and questioned contemporary concerns like the nuclear arms race. The nuclear mushroom cloud is a persistent motif that appears in many works as the artist sensed a world moving towards a larger conflict.

Beyond this threshold lay, ‘The Inner Sanctum.’ Enveloped in soft light that focused on the art, the room had a calming effect on the senses. The paintings that hung here were veterans of important shows like the prestigious Venice Biennale where his work was exhibited in 1997. Zahoor had the privilege to be the creator of the largest portrait of young Mohd. Ali Jinnah. This six foot by six foot portrait had pride of place in the show. Also on display were prints of the ‘Homage aux Prix Nobel’ series commissioned by Sweden’s Gallerie Borjeson soon after Pakistan’s Abdus Salam became a Nobel laureate. Nowhere was this sentiment more evident than in the content of his art that simultaneously chronicled and questioned contemporary concerns like the nuclear arms race. The nuclear mushroom cloud is a persistent motif that appears in many works as the artist sensed a world moving towards a larger conflict.

Zahoor’s commitment to art education in Pakistan can be seen throughout his career. He was instrumental in the revival of miniature painting at NCA, which led to the flowering of the neo-miniature school of Pakistani art. In the memory of his commitment an ambitious educational outreach programme around the show has been developed.

With the help of a grant from the Trillium Foundation, a specially designed activity book for students of grades three, four and five will help them to discover more about Pakistan, art and the artist Zahoor ul Akhlaq. This is the first time some 20,000 Canadian school-children will be directly engaged with the art and culture of Pakistan.

The inspiration for ‘The Passion of Zahoor ul Akhlaq’ came from a similar takhti show held in Karachi three years ago in which 125 artists participated from all over Pakistan, Canada, UK, USA and the UAE. This was a self-funding project in which the funds were generated through a raffle of the takhti works of art on display. ‘The Passion of Zahoor ul Akhlaq’ was organised and hosted by LAAL and The Art Gallery of Mississauga. LAAL was founded by Sheherezade Alam, shortly after the tragic and senseless murder of her husband Zahoor ul Akhlaq and daughter Jahanara. This organisation focuses on the documentation, conservation and presentation of the cultural heritage of Pakistan for the next generation. The success of the inaugural event that was attended by almost 700 people was evident from comments like, “This show made me feel good as a Pakistani,” “This show gave me a chance to see so many Pakistanis at an art event,” etc. It can only be hoped that as the news of this extraordinary show ripples through the Canadian communities it will enable them to view Pakistan as the home of some exciting and vibrant art.