Route to Harmony?

By Syed Talat Hussain | News & Politics | Published 9 years ago

It is a delicious dream: over three billion people connected through a dozen and a half ports and six massive road networks to bind three continents in profitable trade, commerce and business activity. Throw into this fabulous prospect eight existing regional organisations that, at present, club different countries in Asia’s south, west and east besides the Gulf and Middle Eastern region. Imagine if these too can be aligned to share the lofty goal of combined prosperity. There cannot be a better fate-changer than this for a world where poverty and uneven opportunity is driving millions to desperation, dislocation and terrorism. For Pakistan, whose location puts it at the nodal point of this grand alliance, this would be an arrangement made in the heavens.

But like all dreams this one too is too good to be true. In fact realities surrounding this prospect are so tough that even a much more diluted version of the scenario, where different regional hubs interface with each other for mutual benefit while retaining their separate identities, looks dim. Start with the India-Pakistan-Afghanistan alignment. Former Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh summed up this route to rollicking regional times by saying that he wanted to have his breakfast in Delhi, lunch in Islamabad and dinner in Kabul.

Reflecting similar ideals, in the face of formidable domestic opposition many years later, prime ministers Narendra Modi and Nawaz Sharif are trying to push their countries in this direction. The effort also involves President Ashraf Ghani of Afghanistan, whose landlocked nation stands to gain much from the easing of tensions and softening of borders between these two nuclear neighbours. Yet many meetings, moots and exceptional bilateral engagements later, the three countries stand apart. United in their official rhetoric to build a common future, they continue to distrust each other’s motives and policies that each believes aim to undermine the other.

Pakistan blames the recent spate of terrorism on groups operating from the Afghan soil. The country’s powerful army chief, General Raheel Sharif, took the unusual step of calling President Ghani and the US commander, General JF Campbell of the Resolute Support Mission in Afghanistan, to seek support in nabbing those responsible for the latest four-man attack at a university in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, that led to the death of 22, including 13 students and a professor. Afghanistan responded coldly saying they neither shelter nor support any group. The no-cooperation mood in Kabul is partly caused by the weakness of President Ghani’s government that is battling a robust insurgency by the Taliban that is not only sweeping the country’s troubled east and south but also touching the traditionally calmer north. The Kabul government’s writ does not run beyond the capital. But the policy of cold-shouldering Islamabad on the issue is also driven by the perennial complaint of Afghanistan that the entire Taliban resistance is run by Pakistan’s formidable intelligence agency, the ISI, and the army. This impression is so deeply ingrained that despite various confidence-building efforts, President Ghani, who was once a perfect counterfoil to his mercurial predecessor Hamid Karzai’s visceral hatred for the Pakistan Army, at first refused to show up for a recent Heart of Asia conference hosted by Islamabad. It was only after Washington intervened that he changed his mind and reluctantly made the journey.

But his view of Pakistan’s role in fomenting trouble in Kabul still holds. This is reinforced by the growing Indian influence in Afghanistan: successive Pakistani governments have accused Delhi of staging a proxy war in the country’s volatile province of Balochistan, besides encouraging assorted groups to carry out terrorist strikes in the other bordering province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Delhi, of course, denies these accusations and, in turn, unfolds its long litany of complaints of Islamabad-funded and abetted terrorism on its own soil. The world-infamous Mumbai attacks in which Pakistan-based groups were involved and the more recent attack on the Pathankot Airbase claimed by groups from the disputed territory of Kashmir have evoked deep passions of war and distrust between these two traditional rivals. The Indian defence minister openly spoke of ‘inflicting pain’ on those involved in the airbase attack — a reference that everyone understood to mean Islamabad. Since then there have been half a dozen attacks inside Pakistan in which over 125 people have been killed. Many in Pakistan view this as evidence of the Indians delivering on their threats. Even though in almost all these cases terrorists either got directions allegedly from Afghanistan or had sent their death squads from there, it is widely believed that India is joining hands with Afghanistan’s anti-Pakistan lobbies to bleed Islamabad with a thousand cuts.

Logic dictates that if all three countries are plagued by terrorism, they should combine their intelligence and resources to fight the threat and also abandon the counter-productive policy of using non-state actors to get even with each other. However, so far such suggestions have not found willing listeners in all three capitals. Instead, a more traditional idea is taking root: closing borders. India has already built a long fence on its disputed border with Pakistan from where it alleges infiltration of men and material takes place. It aims to further expand this fencing and take it even to those parts of the border that had traditionally been allowed to function normally.

Pakistan has increased its troop deployment on its border with Afghanistan and almost one-fourth of its 800,000-strong army is now actively deployed on the north-western front. Governments of provinces bordering Afghanistan are already asking for fences to be erected to prevent the flow of drugs, terrorists and weapons. These ideas are inimical to the hope of a regional route that would be free of heavy monitoring encumbrances. These also militate against the entire plan of creating secure trade corridors and facilitating easy movement of goods and services. But like many European countries who are responding to the immigration crisis by revisiting their state of borderlessness, countries here are thinking no differently. In the coming years these anxieties are going to grow as there seems to be no end in sight of the industry of terrorism in this part of the world, more so since the dreaded Islamic State is spreading its tentacles in Afghanistan’s fractured soil.

This challenge of promoting regional harmony is further aggravated by the conflict in the Middle East where a new ‘unsanctioned’ Iran is all set to upturn the traditional hold of Arab States. This poses a grim dilemma for Pakistan, whose leaders have been historically dependent on Saudi dole and oil, but cannot afford to cause affront to their bordering neighbour, Iran. For now, they have tip-toed between Saudi demands to play a more central role in their 34-nation alliance that excludes Iran and Tehran’s expectation of ‘neutrality.’ However, if the Saudi-Iran tug of war intensifies, Pakistan’s precarious fence-sitting might collapse, causing a huge backlash at home where a deadly sectarian strife (fuelled by the proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran) has already taken thousands of lives in the past three decades.

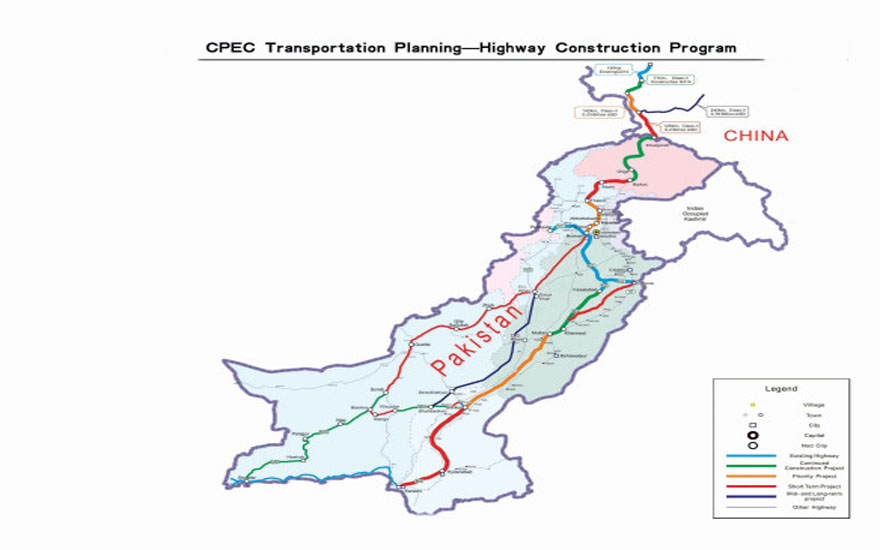

In this mayhem, China’s One Belt and One Road plan, of which Pakistan is a major part, seems to be the only shining light of a shared future. At heart the plan aims to set up an economic land belt that includes countries on the original Silk Road through Central Asia, West Asia, the Middle East and Europe, as well as a maritime road that links China’s port facilities with the African coast, pushing up through the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean. China’s 100-billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank initiative is another mark of its plan to redefine the global financial, political and strategic order. When the world’s second-largest economy moves in the direction of regional integration, it can create an enabling environment for a prosperous future.

Chinese outreach to Iran (the world’s 18th largest economy) and its attempts to broker peace between Tehran and Riyadh, suggest that Beijing is aware of the need for peace between major Asian countries in order for it to sustain and institutionalise its global power. But even Beijing’s clout is not without challenges. India is weary of China’s assertive role. As indeed are Japan and the US. With Japan, China has a mini Cold War going on. Beijing also does not control the dynamics in the Middle East nor does it have much sway over Russia’s influence in Europe and Central Asia. It may offer financial incentives and solid advice but regional politics around its sphere of influence is not taking cues from Beijing.

There is a good reason why Pakistan, which hopes to have investments close to 47 billion dollars through the mega China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (part of the One Belt One Road Plan), is more keen on keeping ties with China on an even keel than on anything else at the moment. Like most economically dependent countries in this region, Islamabad understands that the best bet to pull through tough times ahead is to simply cling to China’s coattails.

This article was originally published in Newsline’s February 2016 issue.

The writer is former executive editor of The News and a senior journalist with Geo TV hosting a prime time current affairs program.