New Kids on the Block

By Zarmeene Shah | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 16 years ago

A show featuring work by Pakistani artists, ‘Hanging Fire: Contemporary Art from Pakistan,’ opened at New York’s Asia Society Museum on September 10. A preview in The New York Times aptly called it one of the most highly anticipated events for Pakistan’s art community. Curated by Salima Hashmi and featuring the work of artists seen to be at the forefront of contemporary art in the country, ‘Hanging Fire’ is the first major show of contemporary Pakistani art to open at a major American museum. The relevance of its import is not restricted to the artists involved in the show, but also pertains to the domain of the larger humanities, as well as to the country at large for bringing to the fore a critical segment of society, the existence of which the United States has remained, for the most part, unaware.

Pakistan’s troubled history has not only been responsible for turmoil within the country but also has led to a fundamentally tunneled vision through which the rest of the world has come to view it — a tunnel at the end of which exist religious fundamentalism, nuclear warfare, political conflict and terrorism. In the last few decades, the media has served to embed a particular image of Pakistan into the mind of the world; a gruesome, terrifying and violent image. Underneath this image, its cultural language has been reduced to a whisper. A language that once resounded quite strongly with the voices of the keepers of its culture such as Faiz, Bhittai, Iqbal and then, those whose language took a different form but was just as powerful: Chughtai, Sadequain and Nagori among others. What this show does, then, is to throw light upon a component of society that is critical to forming a perception of that country — a light that takes the image of unreasoning brutality and endows upon it the light of intellect. It does not so much as help the world in the ‘discovery’ of Pakistani art as it does in ‘revealing,’ or a ‘rendering visible’ as Foucault calls it, of those things that have always existed, but have been pushed into invisibility.

It is then apt that ‘Hanging Fire’ invokes one of its most recent great voices that has echoed and visibly left its mark on those who have heard it and followed in its tradition: that of Zahoor-ul-Akhlaq. Akhlaq’s work and practice reflected a keen sense of awareness of the issues of South Asian artists of the time, as they navigated not simply through their own colonial history, but also with a sensitivity to the rest of the world, to Modernism and to the global dialogue in which they sought to partake. He brought to Pakistani artists an acute understanding of what it was to be an artist in the world, rather than one that operated simply within the insular bubble of a country’s borders. The four large pieces on show at the Asia Society are a tribute to the undeniable influence of an artist who can be rightly called the father of contemporary Pakistani art.

This keen sense of reflection on socio-political issues is a significant thread that ties many of the works and the artists in the show together. The key to the success with which this reflexivity is delivered, and then received, is the ability to make it at once accessible to people who may not be familiar with the cultural innuendos that it puts forward, while at the same time making it intimate enough for those that are. This is the quandary of the artist in the present day. To communicate effectively in a world where the lines between cultures, stimuli and the influences that cultures project onto each other become harder and harder to distinguish. Several of the works in this show tackle this complexity head-on.

Bani Abidi’s video piece ‘Shan Pipe Band Learns The Star Spangled Banner,’ a seven-minute film of a brass pipe band in Lahore that the artist commissioned to learn the American national anthem, is a paradigmatic and witty look at the way in which societies receive, improvise and reinvent that which seeps into their culture, leading to a dysfunctional hybrid that is eagerly adopted without an understanding of the contextual framework. Abidi’s work, always clever, humorous and loaded with political implications, straddles the fence between being able to carry out a socio-political commentary, simultaneously at a national and international platform, almost effortlessly.

This socio-political reflexivity, this time very much through the encounter and experience of a woman, is also apparent in the works of artists Naiza Khan and Adeela Suleman. Although the aesthetic and the manner in which both artists process these issues through their work is at first, deceptively different, positioned opposite each other, these works communicate and play off the underlying sociological presumptions and political underpinnings that run through each artists’ practice.

Naiza Khan’s practice has explored the contradictions, political implications as well as the anthropological implications of the female form, not simply in the context of identity and geography, but also at a larger level — a level that is not confined by the limits of a culture or tradition, but instead reaches over and through boundaries and confines to speak to an audience that is able to intrinsically and intuitively understand her language. ‘Spine,’ constructed of galvanised steel and red suede leather, at once evokes dichotomist images of sensuality and constraint, of protecting and restricting, of a shamelessly decadent adornment of the female body and a shamefully voyeuristic look into a private space.

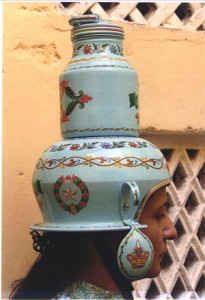

Adeela Suleman’s armour sculpture made from pots

Suleman’s work, on the other hand, brings politics, ethnography and feminity into play through an entirely different set of tools. Her photographs are endearingly amusing at first glance, her armour constructed of metal pots and food containers, and then sumptuously embellished. The dichotomies, amusing as they are, are hard to ignore: the benign materials used to construct protective devices; the seemingly delicate, feminine decorations rising out of a tradition of painting and embellishing heavy trucks and buses; and the sweet, placid pieces arising out of the culture of a frenzied metropolis.

Hamra Abbas’s sculpture, ‘Ride 2,’ a large red figure of the buraq, also summons the motifs of mass transportation vehicles, popular culture and imagery, and magical cultural history. A winged steed with the head of a woman, ‘Ride 2’ not only speaks the language of a Muslim history, and to Western mythological references to magical creatures such as the chimera, but also explores the culture of a will to fantasise that implies a sense of hope and freedom.

Strictly analysed, there are of course problems with the show, such as the lack of a clear curatorial agenda, the insufficient attention given to the positioning of the works and the sequence in which one encounters them, the scale of the wall text that makes it seem as though it is competing with rather than supplying information about the pieces, the question of whether certain pieces do communicate at all with the rest of the show or not, or the fact that there are perhaps too many works in a space not large enough to do justice to such a number. However, by and large, these issues are overshadowed by the strength of a large number of works in the show, and by the fact that they are able to participate in a dialogue that is current, relevant and global. In his book The Return of the Real, Hal Foster speaks of a new paradigm. Referring to the notion that Walter Benjamin put forward in 1934 of the artist as producer, he puts forward a new notion: that of the artist as ethnographer. “[But] the subject of association has changed: it is the cultural and/or ethnic other in whose name the committed artist most often struggles. However subtle it may seem, this shift from a subject defined in terms of economic relation to one defined in terms of cultural identity is significant.”

If, indeed, this new paradigm is defined by a socio-political critique that is based on an engagement with a cultural identity, that takes into account the micro and the macro, an identity of the individual as part of a larger cultural identity in the world, then ‘Hanging Fire’ comes to New York at a perfect time: it brings Pakistani artists forward and locates them perfectly in the midst of a global dialogue that they are clearly already adeptly engaged with.

Click on any photo to begin the slide show displaying art from ‘Hanging Fire’.

Photos: Courtesy Salwat Ali