The MQM’s New Reality

By Mazhar Abbas | News & Politics | Published 23 years ago

Nowhere was the apathy that marked Election 2002 more apparent than in the streets of Karachi, which remained deserted on October 10, till 1 p.m. Most voters came out only when “unknown persons” threatened cable operators to “shut or cut.” Election results of the powerful ethnic party, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), in the city they once virtually ruled, shocked the party. Though the MQM emerged in the lead in the urban centres, with 13 NA and 33 PA seats, voter sentiment had undergone a sea-change.

Nowhere was the apathy that marked Election 2002 more apparent than in the streets of Karachi, which remained deserted on October 10, till 1 p.m. Most voters came out only when “unknown persons” threatened cable operators to “shut or cut.” Election results of the powerful ethnic party, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), in the city they once virtually ruled, shocked the party. Though the MQM emerged in the lead in the urban centres, with 13 NA and 33 PA seats, voter sentiment had undergone a sea-change.

Some MQM polling agents openly admitted that the voter turnout had never been so low. “This was the first time we waited for our voters,” said a MQM polling agent in Gulshan-e-Iqbal, an MQM stronghold.

MQM deputy convener, Nasreen Jalil, who herself lost from the Defence-Clifton constituency, admitted that while the results were surprising, it was not the party graph that had taken a nose dive. She maintains that religious extremists were given seats to strengthen the impression about the presence of Al-Qaeda in the city, as certain quarters wanted to discourage investors from coming to Karachi. “I am not ready to believe that the results were influenced by a pro-religious wave in the country. Had this been the case, the results in Punjab would have been different as the majority of these religious parties and Jihadi groups come from there,” says Nasreen Jalil. “The government gifted NWFP to the MMA to check American influence, and by giving them a few seats in Karachi, they passed a signal to investors to turn to the Punjab.” Having said this, she admitted that there were organisational weaknesses as well. The party failed to check voter lists, and as a result many voters, particularly the “debut 18-year-old voters,” could not cast their votes.

Though the government had allowed 18-year-olds to cast their votes, many could not, as they did not hold national identity cards, while the returning officers refused to accept receipts of those who had applied for one. These were the first elections since 1970 that the minorities were also allowed to cast their votes on general seats. The PPP and the MQM were the main beneficiaries of the minority vote.

However, the chief of the Muttahida’s rival faction, the Mohajir Qaumi Movement, Afaq Ahmed, said his “pro-mohajir” stance also created a dent in Altaf Hussain’s ranks. “The defeat of Aftab Shaikh in Hyderabad and the Muttahida’s failure to win from mohajir-dominated constituencies, particularly in interior Sindh, was due to our campaign. The mohajirs reacted adversely when Altaf decided to include Sindhis in the Muttahida ranks,” said Afaq.

However, the victory for the unknown Sindhi, Aziz Brohi, from the mohajir-dominated Azizabad, still reflected Altaf Hussain’s hold on the mohajir vote bank. Though Altaf’s pro-Sindh politics did affect a section of its extreme mohajir votes,” it was a decision in the right direction,” said a political analyst.

However, the victory for the unknown Sindhi, Aziz Brohi, from the mohajir-dominated Azizabad, still reflected Altaf Hussain’s hold on the mohajir vote bank. Though Altaf’s pro-Sindh politics did affect a section of its extreme mohajir votes,” it was a decision in the right direction,” said a political analyst.

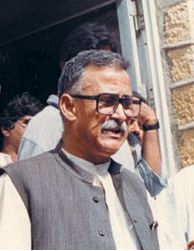

It was this change in politics which has defused the long standing tension between the MQM and the PPP. In fact, on certain issues like provincial autonomy, the Kalabagh Dam, Thal Canal and the NFC awards, the MQM is ahead of the PPPP now, because of the latter’s federal stance. “The PPPP and MQM are natural allies and they should work together,” remarked MQM’s powerful secretary general, Dr Imran Farooq, once considered a hardline mohajir leader.

The PPPP’s Sindh President, Nisar Khuhro, who has been tipped as the next chief minister in case of a PPPP-MQM alliance, welcomed Imran Farooq’s statement. “We have held talks and are moving in the right direction,” said Farooq. “If we are able to forget the past and admit our mistakes, there is little difference of opinion on basic issues.” The MQM’s recent pro-Sindh stance on many issues has brought the two parties closer.

Despite losing in interior Sindh, the MQM has made inroads, particularly in constituencies dominated by the minorities. “I am member of the Pakistan Peoples Party, but I have no hesitation in saying that I am impressed with the MQM, particularly their dealings with the minorities. Unlike other parties, which gave tickets to influential Hindus, they gave tickets to poor Hindus on general seats,” observed former MPA Hari Ram, who predicts a bright future for the MQM. “It is also a wake-up call for the PPPP and I have told my PPPP friends that the MQM is our natural ally,” Ram said. However he did express his apprehensions that Altaf Hussain might return to his old stance, given the MQM’s setback in Karachi and Hyderabad.

Some of the results, however, have given rise to much speculation regarding the fairness of the electoral process. Two MQM stalwarts, deputy conveners Nasreen Jalil and Aftab Shaikh, were among those who lost in the October elections. According to Jalil, on the night of the elections, she receieved a telephone call from Brigadier Akhtar Zamin, principal secretary to the governor, who informed her that she had won. “I won on October 10 and lost on October 11,” she said. She lost to former mayor of KMC and veteran Jamaat-i-Islami leader, Abdus Sattar Afghani. In the last elections, the Jamaat Amir, Qazi Hussain, came fourth after the PML, MQM and PPP.

The PPPP, too, has protested over results on at least two seats: one which was lost by Iftikhar Hussain by nearly 400 votes and the other which was contested by Mohammad Bux Lashari. “We were winning on at least five seats but results were changed in the morning,” says Nisar Khuhro. While in the past, the MQM had lost from Clifton, the real shock came from its stronghold, Hyderabad, when its senior-most leader after Altaf Hussain and Imran Farooq, former mayor of Hyderabad, Aftab Shaikh, lost to the JUP-MMA candidate by nearly 1,000 votes. Similarly, defeats followed in Tando Adam, Mirpurkhas and Nawabshah.

Despite their losses, the MQM still hold the key to the formation of the Sindh government. Almost all party leaders have visited the MQM’s headquarters, 90, and held talks with them over the formation of the Sindh government. According to inside sources, the Pakistan Muslim League, PML (Q), the Sindh Democratic Alliance, and the National Alliance, have all offered the top slot to the MQM in Sindh while both PML-N and PML-Q have also agreed to give up a major share at the centre in favour of the MQM.

According to political observers, however, given the MQM’s political stake in interior Sindh, unlike the past, Altaf Hussain wants an alliance with the PPPP. Should the MQM decide to go with the Punjab faction, dominated by President Musharraf’s “blue-eyed” boys, they stand to lose their political clout in Sindh.