The Experience of Existence

By Shahana Rajani | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 15 years ago

“Being There,” a show of eight women artists — Hamra Abbas, Risham Syed, Nausheen Saeed, Masooma Syed, Mahreen Zuberi, Seema Nusrat, Sara Khan and Nosheen Iqbal — opened at Koel Gallery early March. Curated by Adeela Suleman, the exhibition saw artists exploring different aspects of existence and experience. The works negotiated the three-dimensional space rather than remaining flat, employing a playfully deviant strategy to unsettle the viewer’s social, psychological and cultural assumptions.

One of the first works to confront the viewer was Nosheen Syed’s sculptures of the female body. A forceful rendition in aluminium, it embodied a healthy, curvaceous but ungainly woman. The artist’s intention behind casting these bodies in metal was to present women as ‘solid, permanent and heavy,’ contradicting their marginalised, almost invisible existence in Pakistan’s conservative society. Though the sculpture’s medium and volume reinforced its presence as an indestructible life force, the female bodies stood headless, voiceless. Their necks and shoulders were chained and clamped — an oft-repeated formula for stressing the subordination of women. Although in itself an unoriginal concept, Syed’s rendering of the sculpture was refreshingly sensitive, portraying a fleshy yet harsh sexuality and the simultaneous strength and vulnerability of the female body.

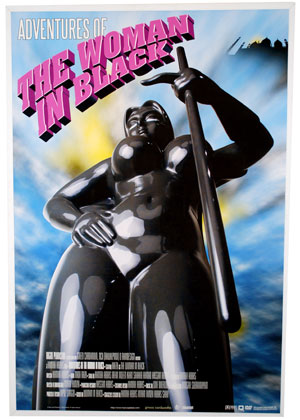

‘Adventures of the Woman in Black’ by Hamra Abbas

While Syed showcased the suffering of women, Hamra Abbas played with the idea of a female superhero in her poster titled ‘Adventures of the Woman in Black.’ The work was borrowed from her exhibition at Green Cardamom in 2008, for which she had created a voluptuous two-metre-tall shiny black fiberglass figure titled ‘Woman in Black.’ Abbas drew inspiration from the iconic press images of burqa-clad women yielding sticks as weapons when the Red Mosque in Islamabad was stormed by government troops. Refraining from trite comments, she embraced the idea of an assertive female power within a world overshadowed by militant violence. The Muslim woman is no longer shown as a victim of a male world, but rather as independent and empowered, her sex no longer hidden but brought into focus. This sculpture reappears in two-dimensional form in her poster, replicating the layout of a movie poster. It is largely through television that cultural stereotypes of the ‘other’ have been propounded to sustain certain power hierarchies and Abbas reverts back to this medium to promote and ‘advertise’ her own feminist agenda.

Seema Nusrat also explored gender issues. She constructed an armour-like female ensemble made from belt buckles, hung from the ceiling. It confronted the viewer with a conflation of masculinity and femininity, of repression and violence with a new sense of empowerment as the artist hijacked this symbol of masculine power and potency, recontextualising it within a feminine, concave form.

‘Untitled I’ by Seema Nusrat

Nosheen Iqbal’s works shared a similar materiality. While her compositions were based on Persian and Mughal miniatures, Iqbal constructed her imagery from internal parts of a wrist watch. Her process, therefore, retained the physicality of performance and meticulousness distinct to miniature painting. Her figures echoed the mechanics of a watch, becoming a pressing reminder of mortality. Her appropriation of an everyday object, bringing it into the sanctified space of the miniature, negotiates and redefines the boundaries of miniature painting.

Sara Khan had on display a miniature sculpture, ‘PK2010,’ which dealt with the problems of always “being there” to witness violence and terrorism. The artist ironically showed a baby seeking refuge from the city’s explosions and blasts, within a grenade shell. It reflected what the artist viewed as the doomed condition of the youth of Pakistan, who have nowhere to turn for security and are being pulled into the whirlpool of violence. The minute scale magnified the fragility and vulnerability of the embryo-like child, increasing its state of helplessness. The grenade shell resembled a walnut, but also a menacing, threatening insect, further victimising the baby, whose only sin is its mere existence.

Mahreen Zuberi continued on the themes with a political comment. She recorded certain high-risk buildings in Karachi, listing down minute details of the building materials used for increased security. Concrete blocks and barbed wires have become an inherent part of the city’s landscape, yet by placing a taweez next to these recordings, Zuberi showed that such measures are no more than a ‘tor’ for eliminating security risks. Just like thetaweez does not rationally provide protection but is based on superstitious belief, these added security measures also merely provide psychological comfort rather than actually preventing anything.

‘PK2010’ by Sara Khan

Moving away from socio-political issues, Risham Syed challenged the art world, teasing the art connoisseurs. In her work ‘Landscape,’ the board surface was covered with a thick layer of plastic grass. The grass surface mocked the pretensions of high art, showing the futility of aesthetic experience and bringing into crisis aesthetic taste. The plastic grass — looking deceptively real from a distance — showed how art is never more than the appearance of reality, always constructing its own truths. It commented on the power of the gallery to transform whatever it displays into art, and the obedience of its viewers who believe, digest and aestheticise everything that is presented to them. Masooma Syed played with the viewer in a similar vein. On her yellow coloured canvas, she had printed the words ‘Process Yellow,’ ridiculing the postmodern tendency to question and probe the process rather than be satisfied by the outcome.

Together, the artists explored the physicality of their mediums, every work having a strong, distinctive presence that provoked the viewer to engage with it on both formal and conceptual levels.

The exhibition brought together a diverse voice of artists, who chose to comment on different aspects of living, from issues of identity and belonging, to violence and terrorism. Their works temporarily arrested the separation between ‘here’ and ‘there,’ unsettling the viewers out of their daily complacencies.