Playing to the West

By Aquila Ismail | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 22 years ago

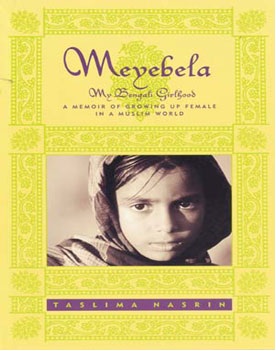

The problem with reviewing memoirs is that one tends to look at its contents, more than its literary value, which Taslima Nasrin’s Meyebela largely lacks anyway. It also comes with preconceived ideas about the subject. The substance redefines the author, and , in this case, it helps understand what led to her being reviled by her country , and adulated by the west.

The problem with reviewing memoirs is that one tends to look at its contents, more than its literary value, which Taslima Nasrin’s Meyebela largely lacks anyway. It also comes with preconceived ideas about the subject. The substance redefines the author, and , in this case, it helps understand what led to her being reviled by her country , and adulated by the west.

The starting point of Meyebela is 1971, when Bangladesh was born out of much bloodshed. The nine-year-old Nasrin, along with her family, is sent off to live with relatives in the countryside until the violence has died down. The birth of her nation is conveyed through a truck filled with young men shouting slogans of a free Bangladesh. The family returns to their home in Mymensingh, a small town in Bangladesh. The narrative moves back and forth, bringing within its folds the life of her philandering, brutal father and emotionally distressed mother, who seeks to find solace in religion through the medium of a pir. The combination of these opposing forces shape the author’s sensibilities of the world. One wonders then if Nasrin really delved into the real precepts of religion or had she simply given in to her own experience of an obdurate, fanatic, almost illiterate mother, and a beastly father, when she made the statement about the need for revision of the texts.

The family is certainly dysfunctional, to say the least. The father, a doctor, is prone to brutally beating his children at the slightest pretext, and is not averse to laying his cane across Nasrin’s back for failing to secure a certain grade, or not showing an inclination to study 24 hours a day as demanded by him. Indeed, he has an almost destructive desire to control his children. Her brothers disappoint the father; in fact, the younger one runs away from home to marry a Hindu girl and is later subjected to the worst possible physical punishment. The older one too leaves home to go to Dhaka. This leaves the two sisters, who then face his wrath on an almost daily basis, and Nasrin is so terrified of him that she cannot even bring herself to speak in front of him. It is thus clear where her belief, that all men are prone to great violence against women, comes from.

The mother’s way of dealing with her husband’s romantic/sexual shenanigans is to plunge into religion. She is introduced to a local pir Amirullah, through a female relative, and proceeds to become his devoted disciple. She turns into a fanatic, deeming even her family a bunch of infidels. She follows Amirullah’s every dictate to the point of being ridiculous, ‘Now Ma and the others were fighting over Amirullah’s paan juice as if it was some heavenly nectar. Ma certainly was convinced that although the paan had been chewed, it was no ordinary man who had chewed it….If she ate the paan from Amirullah’s spittoon, a place for her in heaven was guaranteed…’ Of course she expects Nasrin to follow her in her devotion to the pir. Nasrin is made to hear his description of what will happen to those who go to hell, to be stung by scorpions and snakes and fed boiling water and pus. Her distaste for religion grows from such encounters. Ironically, later in life, the mother has an affair with her brother-in-law to get even with her husband’s sexual adventures with maids etc.

In the west, where people are constantly told that Muslims are uncivilised, it is certain, and unfortunate, that the dark picture that Nasrin paints may be universalised and welcomed eagerly. The mother’s domestic struggles, acting as a precursor of Nasrin’s concept of the larger issues of religion, then become the vehicle for a superficial understanding of the Muslim world. Granted that capricious acts of unstable adults, and its consequent effect on children deserve our outrage, but this happens in families in all parts of the world. Since this memoir is about a woman, beset by extreme parental tyranny, it should have been dealt with in a secular manner, i.e. as an issue of familial dysfunction rather than a treatise on Muslim society. However, because the oppression etc has been given an Islamic character, the memoir has received rave reviews in the west and is even being used as an academic tool. Perhaps if her mother had not sought refuge in the misdirected pir, Nasrin and her memoirs would not have had the fame, or notoriety, they now have.

So while one feels sorry about the terrible experience she had at the hands of her family growing up in a quasi-urban society, for her to define her experience as the experience of all Muslims throughout history, is essentially incorrect. Her interpretation is that of extremists of every religion, who advocate enslavement of women and consider women the repository of all things that contribute to the fall from grace of men. In fact, Nasrin sounds almost like a manipulative child writing what the west wants to hear.

Coming to the aspects of sexuality, there are many subterranean sexual encounters outlined in the memoirs. Nasrin is molested by two uncles. But this is not discussed too much in the book. Her first schoolgirl crush on a senior girl in school is evocatively described: “…her body smelt of fresh flowers. It was like a fairy tale. Runi was a flower — a jasmine perhaps, turned into a princess by some magic spell…I could lay my head on her breast and inhale the scent of jasmine…” In fact, there is much physicality in Nasrin’s portrayal of the female servants, her aunts and childhood friends.

Meyebela is replete with names — too many, in fact — and it may take a while to sort these out. Nasrin seeks to shed light through a string of anecdotes, which is a tool often used in memoirs, but here it is disorganised and repetitive and leaves one unsatisfied with the outcome. Also, from a purely literary point of view, the book does not give much pleasure. One turns the pages to more of the same. The chronology is confused, events are similar and the narrative gets tiresome after a while. It could have been edited to at least reduce its length.

Meyebela is one of two volumes of Nasrin’s memoirs, and encompasses the first 13 years of her life. It was first published in French in 1998, and in Bengali in 1999.One cannot help but wonder if the publication of the book in English in 2002, was because it reinforces the western myths about Muslims, brought to the surface after 9/11.

No more posts to load