Firing the Imagination

By Sheherbano Hussain | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 22 years ago

No creative medium, ever since the onslaught of the industrial revolution, has suffered greater indifference than the arena of ceramics. It received its first blow when large china factories began to get established in countries like Great Britain in the late eighteenth century. This trend marked the beginnings of a depersonalisation in this field — skilled artisans’ mass-produced vases, pots, tea-sets and dinnerware were given preference over individual creations by ceramists and craftsmen.

However, thanks to the ancients, countries and regions with a rich cultural heritage and a strong clay legacy such as Mexico, Australia, Greece, the Middle East, the American south west and the Indian subcontinent, continued to produce ceramists who somehow managed to preserve the traditions of their forefathers by working virtually in isolation. The rewards for this ongoing struggle were reaped in the latter half of the past century when small revivalist groups in this field started to crop up, especially in countries like Canada, Australia and Holland. While modern day ceramists still don’t enjoy the status of other visual artists like painters or sculptors, their lot is a far happier one than it was around 50 years ago.

In Pakistan, the field of ceramics remains largely neglected; institutions and colleges, with the exception perhaps, of NCA, Lahore, allocate little to no funds to this area of study, forcing ceramics enthusiasts to find their own way of pursuing or furthering their talents. Some however, have greatly benefited from interacting with local craft potters or kumhars whose earthenware pots, toys and other utilitarian vessels still fire the imagination of many modern ceramists.

A few years ago, renowned artist Meher Afroze, art critic Niilofur Farrukh and designer Shanaz Siddiq founded ASNA, an organisation “committed to furthering the awareness of Pakistani contemporary arts and its strong links with tradition through exhibitions, workshops and documentation.” After holding two successful ceramics exhibitions on a national level, ASNA showcased the first International Ceramic Triennial at the Karachi Arts Council this April, with entries from Pakistani, as well as Bengali and Indian ceramists.

Displaying the work of 26 ceramists, the exhibit featured a wide array of styles, both in the vessel and sculptural tradition. While the Bengali entries comprised the work of Mahdi Masud and Sayeed Talukdar — the current head of the ceramics department at the University of Dhaka — the Indian entry was yet to arrive because of customs constraints.

Displaying the work of 26 ceramists, the exhibit featured a wide array of styles, both in the vessel and sculptural tradition. While the Bengali entries comprised the work of Mahdi Masud and Sayeed Talukdar — the current head of the ceramics department at the University of Dhaka — the Indian entry was yet to arrive because of customs constraints.

The Pakistani entries, boasting a variety of forms and styles, included the work of ceramists from all over the country. While ceramists like Tariq Hasan and Ishrat Suharwardy explored the purely utilitarian aspect of ceramics, others like Salman Ikram, Ghania, Shazia Zuberi, Rana Umar, Saba Shahid, Saadia Sali, Munawar Ali and Salahuddin Michhu Khan asserted the creative potential of this limitless medium.

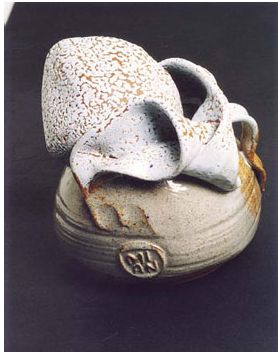

A portion of the exhibit was dedicated to Pakistan’s pioneer ceramist Mian Salahuddin, to pay a tribute to his various contributions in this field. In addition to working as a ceramist since the 1960s, Mian sahib’s presence at the National College of Arts, Lahore, has contributed greatly to its ceramics department, which is churning out a lot of fresh talent today. In this small retrospective display, viewers were exposed to a multitude of styles and techniques, which Mian sahib has experimented with and mastered.

A recent graduate of the NCA, Umar Rana, explored the concept of pain in his work by coiling barbed wire in and around his vases and splashing them with red paint. While entrants like Salman Ikram, Shazia Zuberi, Mahdi Masud, and Saba Shahid created beautiful and complex forms, other like Saadia Salim and Salahuddin Micchu Khan created simple forms, which captured one’s attention with their stunning glazes.

The most evocative entry in the entire display was a collection of eggs by the Karachi-based sculptor and ceramist, Munawar Ali. Using the same size and shape for all the eggs, Munawar employed a variety of methods and techniques to make each egg an individual work of art — some had holes punched in them and sections gouged out, while others were beautifully glazed or painted in a single colour. This collection was a fine example of how such a simple idea can be used to convey so much.

Another noteworthy entry was an installation comprising teacups and tables in an octagonal setting by Ghania, currently a faculty member in the ceramics department at the NCA. Exploring feminist themes in her work, the teacups, unglazed and unembellished, were placed in a variety of settings and arrangements to depict the use and abuse of women, sharing qualities with the American feminist artist, Judy Chicago’s celebrated installation titled, ‘The Dinner Party.’

A seminar was also held on April 7, in which Shazia Zuberi and Ghania spoke about “career opportunities in the field of ceramics.” It is imperative that such talks and shows be held regularly to expose more and more people to this intriguing medium and to clear its widely held misconception as a limited and commercial outlet.