Interview: Zohra Yusuf

By Deneb Sumbul | Interview | Published 6 years ago

“Win or lose, what is important is that you put up a fight” – Zohra Yusuf, Council Member, HRCP

Calm and soft-spoken with a will of steel, Zohra Yusuf’s diminutive frame belies a towering soul that has covered immense ground as a journalist, an advertising guru and a human rights defender. In the early 1980s, Zohra was the editor of the weekend edition of the English eveninger, The Star, and wrote extensively on the media and social and women’s rights issues. Subsequently she joined Spectrum Communication Y&R as Creative Director but continued to write on issues close to her heart for various publications, receiving accolades including the APNS award in 2011 for her feature ‘TV Channels or Electronic Pulpits,’ featured in Newsline. As a human rights defender, Zohra Yusuf became a member of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) in 1988, and was elected to its Council in 1990, serving in various capacities including two, three-year terms as its Chairperson. She was also a bureau member of South Asians for Human Rights (SAHR).

Calm and soft-spoken with a will of steel, Zohra Yusuf’s diminutive frame belies a towering soul that has covered immense ground as a journalist, an advertising guru and a human rights defender. In the early 1980s, Zohra was the editor of the weekend edition of the English eveninger, The Star, and wrote extensively on the media and social and women’s rights issues. Subsequently she joined Spectrum Communication Y&R as Creative Director but continued to write on issues close to her heart for various publications, receiving accolades including the APNS award in 2011 for her feature ‘TV Channels or Electronic Pulpits,’ featured in Newsline. As a human rights defender, Zohra Yusuf became a member of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) in 1988, and was elected to its Council in 1990, serving in various capacities including two, three-year terms as its Chairperson. She was also a bureau member of South Asians for Human Rights (SAHR).

How did you become an activist?

I had friends who were among those who had founded Shirkat Gah, including the late Najma Sadeque (journalist), but the one who really got me into Shirkat Gah was Mariam Ali Baig (Editor, Aurora Magazine), who was a very good friend of Aban Marker (Regional Director, IUCN Asia). I got into activism through Shirkat Gah, which had been set up in 1975. I joined in 1978.

Shirkat Gah had more to do with research and documentation, and was not exactly an activist organisation, in the sense that it was not involved in street protests. However, there were other women’s rights organisations such as Tehrik-e-Niswan and the Democratic Women’s Association, which was headed by Mumtaz Noorani. The All Pakistan Women’s Association (APWA), was then the largest and the most well-known group; it had been very effective in the 1960s in securing women’s rights to a certain extent, in terms of getting General Ayub Khan to approve the amendments to the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance 1961.

We were all involved in our respective organisations, when General Zia introduced the Hudood Ordinances in February 1979. These were a set of four ordinances, but the one that affected women in particular was the Zina Ordinance that provided for death by stoning, lashes and imprisonment for adultery. When the death penalty is imposed, it signifies a crime against the state. As per this ordinance, an extramarital affair took on the same status because it provided for the death penalty. All of us were disturbed by it but no one really considered its repercussions and there was little response from women’s groups.

At least not until 1981, when the judgement in the Fehmida-Allah Buksh case was announced. In what became the first verdict of its kind, the man (Allah Buksh) was sentenced to be stoned to death and the woman (Fehmida) – then a minor – was awarded 100 lashes in public. The two had eloped and the date of their nikah was disputed. The judgement jolted the women into action and, in the process, brought about the birth of the Women’s Action Forum (WAF).

People have different memories of how WAF was formed but my memory is of Najma Sadeque being very upset by the judgement and calling up Aban Marker to say that the women’s groups should get together and come up with a quick response. A meeting was organised at Aban Marker’s residence where, apart from Shirkat Gah, Tehrik-e-Niswan, Pakistan Democratic Women’s Association, APWA and several other women’s groups were represented. It was there that we decided to form a coalition and come together on a single platform. Our immediate concern was this case, but the broader concern was the discriminatory laws against women that were being proclaimed day after day. It was at this meeeting that we decided to form a coalition and come together on a single platform: WAF.

After leaving advertising, I had become a working journalist for The Star evening newspaper. The press was under direct censorship at that point. Everyday, before publication, newspapers would have to submit their stories to the censors in the Press Information Department (PID) and sometimes they would remove matter. It was becoming increasingly difficult to talk about these issues. But I felt very strongly – and not just as a WAF member – that the women’s movement and other such issues needed to be covered, and my then editor, Ghulam Nabi Mansuri, supported me. As long as we did not criticise the military regime, we could write quite a bit about women’s rights.

Even though regulated censorship ended in 1982, and we got breathing space, we still had to excercise self-censorship; the government expected it of us. The Star was the only newspaper at that time which was supporting the women’s movement; even Dawn was not – it began to support the movement only later. I was often accused of turning The Star into a feminist newspaper. We had directives coming to us daily.

There were some landmark women’s rallies held in Lahore and Karachi against Zia’s anti-women laws?

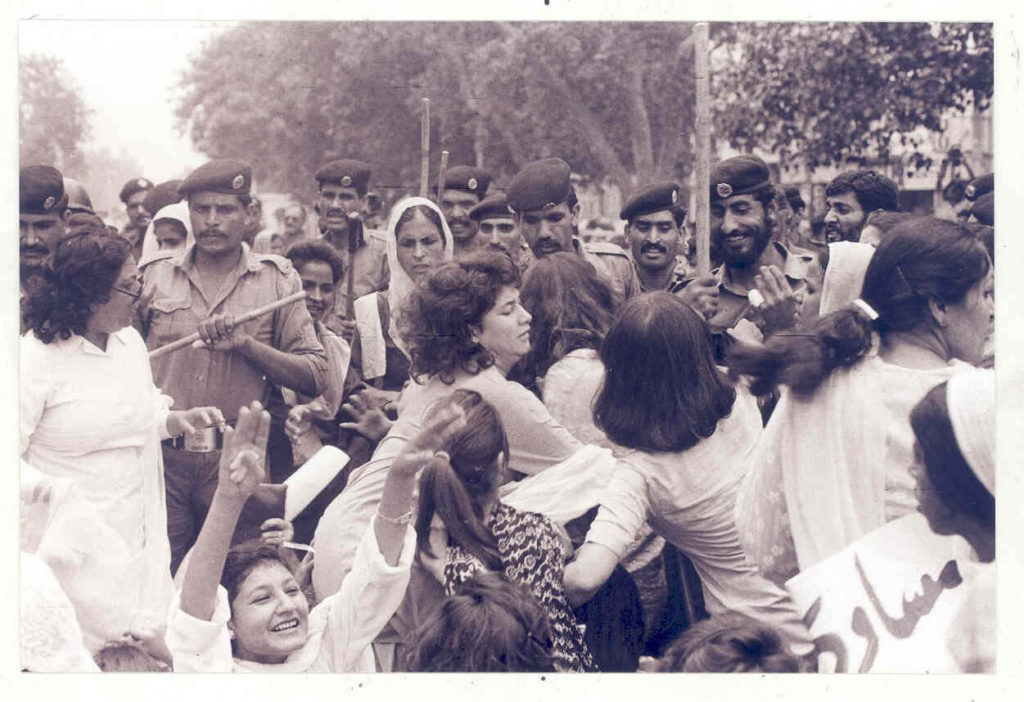

The WAF Lahore chapter, formed shortly after the Karachi one, in collaboration with the Pakistan Womens Lawyers Association, organised a public rally on February 12, 1983 to campaign against the discriminatory laws. More specifically against the Law of Evidence, which stated that the evidence of two women was equal to that of one man. The police came out to disperse the protestors and brutally beat up the women with batons; quite a few of them were dragged by the hair to Kot Lakhpat Jail.

Some days after the incident, another rally was organised at the Quaid-e-Azam’s mazaar in support of the Lahore rally, to which women came out in large numbers. Protest demonstrations were forbidden under martial law regulations and you could be whipped for it, but WAF Karachi went ahead with it.

I believe the WAF movement was covered by the international media.

Yes, I was amazed and really delighted that the BBC was reporting our campaigns against these laws; they said that the WAF was the first serious challenge to the military government. It meant that the international media had taken us very seriously. At The Star office, there would be a stream of journalists from various international news outlets coming to understand the Hudood Ordinances, ask about WAF and the women’s movement. Invariably, they would be pretty shocked that “in this day and age, this is happening to women.”

However, APWA decided to part ways with WAF, saying that Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan would not approve. We realised that they did not want to challenge the status quo and take on the government in any way. Even YMCA got into trouble and WAF was asked to hold their meetings elsewhere. So we started holding meetings at the Karachi Press Club.

Since you became more involved with HRCP, what sort of challenges did you face?

With WAF we were focusing exclusively on women’s rights, but the HRCP works on a much larger canvas. Some months prior to becoming an official member in 1988, I did the first fact-finding for HRCP, which was on the conversion case of a Hindu girl in Mirpur Khas. We travelled to Darul Aman (a women’s shelter) to meet her and her mother. The case went all the way to the Sindh High Court. Sadly, as happens ever so often, before the judge the girl said she had converted of her own free will.

Sometime later, we were confronted with the issue of bonded labour in Sindh. Some haris from interior Sindh had managed to escape and reach the HRCP office in Hyderabad. We had no idea of the scale of bonded labour at that time and it was a massive challenge for HRCP. In Punjab, there is bonded labour in the brick-kiln industry. Asma Jehangir was responsible for drafting the legislation, which was finally adopted with some amendments by the Parliament and passed as the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act 1992.

We are still involved with the bonded labour issue, but over the years, the haris have become more confident. Now they go to the courts themselves and that is a huge success for the HRCP because they now feel empowered enough.

We take up issues that other organisations don’t take up strongly enough. Over the years, different issues keep surfacing. For instance, we spend a lot of our time looking at the status of minorities in Pakistan. While government representatives do speak up occasionally for the Hindus and Christians, they do not do so for the Ahmadis, who are the most persecuted community. When you say Hindus and Christians or the women in the country are in a bad way, then you have no idea what the Ahmadis are up against – they even face social exclusion. You might say then that the women are privileged in Pakistan by comparison.

Then, ever since the war on terror began in 2001, people began to be picked up and disappeared. The issue of enforced disappearances has been a major concern and we were the first to take it up. We went to the Supreme Court in February 2007, shortly before Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudry was sacked by General Musharraf. At that time we had gone to court with about 400 such cases, but ultimately it came down to 240. There has been very little progress on the issue. Now two other issues that really concern us are freedom of the press and the new Pakistan Media Regulatory Authority (PMRA) that the government is coming up with. Journalists are up in arms against PMRA. They see it as tool designed to put further curbs on the media.

Has the policy on PMRA been formulated yet?

The parts that I have read are pretty scary. Earlier PEMRA was responsible for regulating the electronic media and the journalists of the print media had their own organisation; and the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) was responsible for regulating electronic crimes. Under this government, PMRA would be merging all the media regulatory bodies into one authority, that would control every forum of the media – digital, the print, electronic, radio and television. Now the government is going to determine the policies, which is a matter of concern. I don’t know if they will be able to pass the Act through Parliament; their intention is bad because they want to control everything. What bothers us is that this could affect our work.

Also, the government’s attitude towards human rights defenders and NGOs is quite hostile. Although it started during the last government, when Chaudhry Nisar was the interior minister, at least we could talk to their representatives. But now it is very insidious. People from the ISI keep coming to the HRCP offices. It is easier to handle them from the head office, but the harassment extends to our small offices in Quetta and Peshawar, where the staff are asked to fill out proformas and are questioned about their work and funding. They are asked, why are you working on the missing people? Why are you people against the death penalty, are you pro-militant? Why are you pro-militant? Other NGOs are paid similar visits.

There has been a lot of pressure on NGOs and recently, major INGOs were asked to leave. Previously, an NGO only had to register once. Now they have to renew their registration every single year.

Does the new media law put more journalists in danger?

Certainly. During General Zia’s restrictive times, press censorship was defined for you, in black and white. Everyday, we would get an advisory on what we could not publish, and for everything, there was a martial law regulation. When we took out a rally we knew that we were violating a martial law regulation, but we took the risk knowing the consequences.

Now the greatest fear is that no one knows. In those days, no one was picked up and made to disappear. You were arrested and charged under martial law – Zia even had journalists flogged. Now Pakistani journalists and activists receive Twitter warnings, because the interior ministry does not want any criticism of the Saudi Crown Prince Salman on social media. They have blocked several Shia-affiliated websites, because of the altercations between Iran and Saudia Arabia. Under the upcoming PMRA, social media platforms would be told to apply for licenses in order to operate in Pakistan.

How has the women’s movement evolved since the Fehminda-Allah Buksh case?

Several women’s movements have come to the fore, for example, in interior Sindh, Sindhiani Tehreek in particular has been very politically active and a lot of credit goes to Rasool Bux Palijo for organising the women. Similarly, there are quite a few in the Punjab and even in KP. You hear about women becoming active even in smaller cities such as in Dir, where they challenged those who were preventing them from stepping out to vote. All this is incredible because, at least, they are trying to achieve more for themselves.

Although, they are generally more aware of their rights, including political rights, there is always a backlash when women marry of their own choice or express themselves or step out, because of the patriarchal society we live in.

The last parliament made some improvements in the laws on honour-killings, whereby the state becomes the complainant in the case so that there is no provision for diyat or blood-money, as was the practice earlier. And yet there doesn’t seem to be a substantive decline in honour killings. The statistics for the entire country are close to 1,000 honour killings every year.

Changes have been made in the Hudood Ordinances since the Fehmida-Allah Buksh case: General Musharraf made it a part of the original Pakistan Penal Code so now the punishments are not as severe. Adultery is still illegal in Pakistan, but now you are not going to get killed for it.

Sindh has passed the most pro-women laws but the atrocities against women continue almost every day, especially in the interior.

It is not just about enacting laws, their enforcement is equally critical. In the matter of cases of domestic violence, the Sindh High Court (SHC) is angry with the provincial authorities because they have failed to enforce a law passed six years ago – the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act 2013. They have failed to meet the mandatory requirements and procedure in the implementation of the law, and the SHC has asked the Sindh Advocate General to submit whether the rules of the law have been framed or not and has directed the chief secretary to publicise the law.

Similarly when the PPP was in power, it had the best pro-women legislation against sexual harassment at the workplace, against acid-throwing, against traditional practices and customary laws, but again the enforcement was extremely weak. Basically they did not concentrate on the structure, at the ground level and in small places. Worse, the police administration is not even aware of the laws. Whenever we approached the police to inform them about a farm that was holding bonded labour, and that they needed to be rescued, they were completely uninformed about the law.

Additionally, not much work has been done on the implementation and effectiveness of a women’s police force.

Women police were first introduced by the Benazir Bhutto government in 1988, when she set up the first women’s police station. In her second stint as Prime Minister, she brought women to the superior judiciary: Justices Majida Razvi in the Sindh High Court, Nasira Iqbal in Punjab and Khalida Rashid Khan in KP (then N.W.F.P.).

While visiting a women’s police station to follow up on a domestic violence case, I found that the policewomen had an attitude as bad as the men. They said that “It was a private matter and that the couple should settle it among themselves; they should not approach the police.” The women, at times, become part of the same system and need to be better sensitised. So it’s not enough to have a better gender balance. I am sure that there are some enlightened men and women officers, but unfortunately they are the exceptions rather than the rule.

Pakistan has agreed to work on 17 Sustainable Development Goals that we are supposed to achieve by 2030 Where do we stand at this point?

If you look at our international ranking in different sectors, we perform badly. Where women’s economic role is concerned, we are way behind other countries in the region, and compared to African countries, we are just above Yemen and Somalia. In terms of maternal and child mortality, we are slightly better than Afghanistan although we have better structures. It is because of our patriarchal attitude, that women continue to give birth one after the other and there is a lack of access to contraception. Over the years we have improved upon the birth rate, but it is still very high considering our population and way behind Bangladesh, who have managed to control theirs.

We are signatories to several UN conventions but our performance vis-a-vis women leaves a lot to be desired.

Every few years, every country has to submit a report called the Universal Periodic Review to the UN Human Rights Council. In September 2018, it was Pakistan’s turn to submit a report and we presented a very abysmal picture. Not that all the countries on the Council are great – Saudi Arabia is also on that Council – but it is a process that a UN member country has to comply with, and other countries advise you on which areas need to be revisited. Pakistan signed CEDAW at the time of the Beijing World Conference on Women 1995. Although a lot of pro-women legislation has been introduced, the enforcement is so poor that on the ground very little has changed for women.

What are your expectations of the women sitting in parliament, even though most of them came on reserved seats?

Even women on reserved seats have made a lot of difference in the past. In terms of their performance, the best assembly was the one elected in 2008. As compared to the men, the women were more participatory in the parliamentary process. They had raised the most issues and had asked the most questions, so their performance in that parliament was excellent. But since then, it has declined. With the exception of a few in the current assembly such as Nafisa Shah, not many women are vocal. Even the Minister for Human Rights, Shireen Mazari, is hardly heard in Parliament.

How do you view the present level of activism among women?

Basically what brings you into activism or what makes you support causes is something within you, particularly at that point in time, when you see an injustice and you sense you have to do something about it. No matter how effective or ineffective your response might be, you just get involved.

I see some women showing a lot of promise, but I think for them the challenges are fewer than the ones we faced because a lot of ground work has already been done. We faced greater challenges and felt truly threatened. That may not be the case now, so the passion is not as strong as it was then. But I hope to see more women rising because that is what we really need.

I would say that whatever the nature of threats you are confronted with, the spirit of resistance is very important. Remember – first the camel sticks its head in the tent, and then before you know it the entire body is inside the tent. Don’t leave it just for us oldies, it is important for the young people, to be involved as well. And whether you win or you lose, what is important is that you put up a fight.

The writer is working with the Newsline as Assistant Editor, she is a documentary filmmaker and activist.