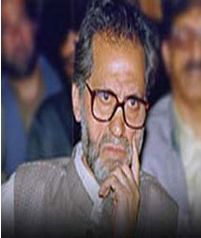

Interview: Abdul Ghani Lone

By Lawrence Lifschultz | People | Q & A | Published 23 years ago

“Our freedom movement has been hijacked by the confrontation of India and Pakistan”

– Abdul Ghani Lone

Abdul Ghani Lone, the Hurriyat leader and Chairman of the People’s Conference, was assassinated in Srinagar on May 21, 2002 at a gathering commemorating the twelfth death anniversary of his friend, the Kashmiri leader, Mirwaiz Maulvi Farooq, also slain by assassins. What follows is an outspoken and detailed interview given by Lone to writer Lawrence Lifschultz, who is currently at work on a book entitled: : Is There A Way Out Of The Impasse? The interview, being published in Pakistan for the first time, took place at Lone’s residence in Srinagar in June 2001. Lone speaks frankly on the “colonial attitudes” of India and Pakistan toward Kashmir and how the Kashmir policies of both countries have consistently failed its people.

Q: Can you describe the history and circumstances that drew you into Kashmiri politics? What was the process that changed you from a member of the Congress Party into an opponent of Congress rule?

Q: Can you describe the history and circumstances that drew you into Kashmiri politics? What was the process that changed you from a member of the Congress Party into an opponent of Congress rule?

A: After I completed my law degree, I came into contact with an interesting judge in whose court I was often arguing cases. This judge said to me: “You also are responsible for what is happening. If the MLAs are trying to intervene in cases, it is due partly to the fact that there is no one to oppose them. You are the first person from your area to have educated himself. You are an advocate now. You must come to the rescue of your people.”

In those days, G.M. Sadiq had formed the Democratic National Council. Sadiq was the only man in Kashmiri public life at the time that I can say was absolutely honest. Sadiq convinced me that if we fight this mighty government of India, we will end up nowhere. Instead, he argued that we should become part of the system and persuade India to recognise that people in Kashmir cannot be ruled by force.

I was convinced. I became an MLA and joined the National Congress. Ultimately, after having served in the Legislative Assembly and having been a Minister [until 1973], I finally came to the conclusion that the system was trying to make me cow down, that I couldn’t contribute anything to my cause.

I believed then, as I do now, that India cannot retain this territory by force. If India had any chance to retain Kashmir, then India would have to convince the people. It is India itself that introduced the basic principle that the people of Kashmir had available to them the “right of self-determination.” The erstwhile ruler of Kashmir acceded to India absolutely without conditions. Yet it was the government of India that in turn declared that this accession would be subject to ratification by the people.

After Partition, when tribesmen from Pakistan intervened and began advancing into the disputed territory, the government of India approached the United Nations. The application that India made under Article VI unequivocally stated that once the territory of Jammu and Kashmir has been cleared of those that had intervened and peace had been restored, the people would be free to decide their future, either through a plebiscite or a referendum — under international supervision. Not only did India make this commitment, but it asserted it again and again, both nationally and internationally. It consistently maintained that the right of the Kashmiri people to determine their future was available to them.

Q: Throughout the ’60s, despite the fact that neither a plebiscite nor a referendum had been held, you still believed that you could make the ‘system’ work on behalf of Kashmir?

A: Yes, we still believed that we could convince the Indians that unless and until you settle the issue of Kashmir with the people of Kashmir, it would be very difficult, if not impossible, to run a ‘normal’ administration in this territory. Either India had to convince the Kashmiri people that they are a part of India or they had to give them the chance to decide their own future.

Q: What finally changed your mind?

A: What happened is that once again India came to terms with Sheikh Abdullah. This was 1975. I thought that if Sheikh Abdullah came to power, he was still in a position to convince his own people. Yet, I was also convinced that Mrs. [Indira] Gandhi was not willing to give Sheikh Abdullah a free hand to rule. In 1976, I issued a statement saying that Mrs. Gandhi should detach herself from the local Congress Party in Kashmir, and permit it to join with Sheikh Abdullah’s National Conference. This would have given Sheikh Abdullah a free hand to rule in Kashmir, he could still have convinced the people to accept India. For this statement I was expelled without notice from the Congress Party. I was then a Congress Party MLA. Nine other [Congress] MLAs supported me.

I also came to the honest conclusion that the old man didn’t have the guts and courage to do anything. He had lost his fire. He was now rather afraid of New Delhi. After having been in jail so long, he was also under pressure from his family at the time.

In 1977, I fought the election on a Janata Party ticket and won. However, within a year I resigned from the Janata Party and formed the People’s Conference. It was the same problem. At that point we were fighting for the restoration of “internal autonomy” in Kashmir.

Q: What did you precisely mean by “internal autonomy”? Had not the provisions of Article 370 already been eroded?

A: When the former ruler of Kashmir acceded to India after Partition, he surrendered to India authority in only three areas — defence, communication and foreign affairs. At the time of the accession, Kashmir was a semi-independent state. In my opinion, Article 370 of the Indian Constitution that was later drawn up had, in fact, nothing to do with autonomy. Article 370 was a bridge used by India to erode the autonomy that we originally possessed following Partition. The government of India could only legislate on those subjects identified by the erstwhile ruler in the ‘Instrument of Accession’. Under that ‘Instrument’, the government of India could only provide administration in the three subjects.

Later Article 370 was introduced. Under 370, the President of India could do away with these limits at any stage, provided the state government made an application to the President and provided this request was supported by the Constituent Assembly of the state. It also stated that any Act passed by the Indian Parliament could be applied to the state of Jammu and Kashmir provided the state government made an application to the President. What happened was that this state’s governments went on producing applications and the President started issuing presidential orders. By those presidential orders, our autonomy was subverted.

The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of India was extended into J&K in various ways. The authority of the Auditor General of India was introduced. The permit system was abolished. At the time of the accession no one was allowed to come to Kashmir without a permit issued from Srinagar. We had our own Income Tax Department. We had to surrender that as well. The right of citizenship was also taken away from the Kashmiri state. By this I mean Kashmiri citizenship. During the Maharaja’s time, only residents of Kashmir could acquire land in Kashmir. Others could not directly purchase land. They could only lease it.

In 1964, the biggest blow to our autonomy occurred during Ghulam Mohammed Sadiq’s government. The “Presidential Application Order of 1964,” took away what we call the “Nomenclature.” Until then Kashmir had its own head of state, the Sadr-e-Riyasat or President, who was elected by the state legislature, and the President of India would, in turn, formally recognise him as Sadr-e-Riyasat of J&K. The qualification was that he must be a state subject — a citizen of J&K. No one else could become President. The Prime Minister was the head of administration. There was no Governor then. The first Sadr-e-Riyasat was Maharaja Karan Singh. He was also the last. The People’s Conference, a party we formed after I resigned from the Janata Party, was committed to a restoration of Kashmir’s “internal autonomy.”

Q: In 1987 there was an election in Kashmir that, in retrospect, represents a watershed. Many people date the emergence of the present militancy which has spanned the last decade from the intense alienation that followed the election. The election is generally considered to have been rigged at various levels. Bring me to where we are today, and tell me where we are going tomorrow.

A: We don’t know about tomorrow, but at the moment we are nowhere. You see the colonial attitudes of Indians and Pakistanis. We have been in “this moment” for the last twelve or thirteen years. Our belief is that this dispute has taken the lives of more than 70,000 people. We know that more than 15,000 houses have been blasted or torched by the Indian army. More than 3,000 people have been killed while in custody. Approximately the same number have ‘disappeared.’ Thousands of our daughters and sisters have been raped or molested. These have been the weapons of war used against us. We have suffered all these sacrifices.

It is as if we have suffered only for their pleasure. It is as if there isn’t a freedom struggle going on. It is made to appear as if there is only a dispute between India and Pakistan. Our freedom movement has been hijacked by the confrontation of these two countries. So we stand nowhere.

Q: If the Kashmiris were able to have a real voice, what would a “just solution” to the Kashmir question look like? Over many decades India and Pakistan have been stuck in intransigent positions. They tacitly accept that there are only “two options” for Kashmir and each rejects the option the other supports. Do the “two options” represent a plausible way forward or does a “third option” exist?

A: Yes, I believe if it is left to Kashmiris they will go for the “third option.” If a plebiscite had been held within three or four years after Partition, the results might have been different.

Q: At that time would a majority of Kashmiris have voted to accede to Pakistan?

A: No, quite the opposite, the vote would probably have gone in India’s favour at the time. However, with the passage of time, the Indians began to show their face to the people.

Q: Could the vote on a plebiscite have ever gone in Pakistan’s favour?

A: One can’t possibly say for certain. But when Pakistan intervened with tribesmen [from NWFP], the men they used started looting after they arrived. They started killing people. People were killed because of their faith. There were massacres in Baramulla and other places. There was brutality.

Q: If there was a genuine possibility of “self-determination,” would you support a “third option”?

A: Yes, that is my honest belief and that is my party’s position.

Q: Are there any differences between you and the JKLF’s Yasin Malik on this question?

A: I don’t suppose on this question there is any difference. Since the Hurriyat was formed, we took a view that it was not profitable for our movement to suggest any specific option at this stage. Those in favour of Pakistan would suggest that “accession” to Pakistan was the right course. The pro-independence people would argue for their position. By prematurely putting forward “positions,” the basic issue that must first be addressed would be sidelined. The basic issue is that India should first concede that Kashmir is a disputed territory. Instead, they say “nothing doing…this is an ‘integral part’ of India…accession [to India] is final.”

I told my colleagues, “Why should we break our heads on this issue? Our Kashmir is with India. They say it is an ‘integral part’ of India. Why should we as Kashmiris fight over whether Kashmir should ‘accede to Pakistan’ or be ‘independent’? It is with them. Let us first persuade the Indians that they should concede that Kashmir is a disputed territory and its future is yet to be decided. Once they do it, then comes the question of how we will solve the issue of this disputed territory.” To me this is the logical approach.

Q: You spoke earlier of the “colonial attitudes” of India and Pakistan. Can you give your assessment of Pakistan’s role in the Kashmir dispute? When you met Musharraf, did you ask whether or not he was open to a “third option?”

A: I did not discuss the issue with him directly in this way. However, I did make a specific point to him. I had also discussed the same matter with representatives of Pakistan from previous governments. We said to the Pakistanis that they should try their level best to help Kashmir get out from being an Indian possession, but in doing so they should not express a preference for any option. Otherwise, they would create problems for our freedom struggle. We told them, “You are just our supporters. You should project yourself as our supporters and not as ‘owners’ of Kashmir.”

In relation to the presence of “foreign militants” in Kashmir there has been a big controversy here. When I was in Pakistan [in 2000], a dinner party was hosted in my honour by the head of the Jamaat-i-Islami of Azad Kashmir, Rashid Peravhi. There were many Pakistanis attending. I gave a speech at the dinner where I said it is important that you understand what are our differences as Kashmiris with India. The simple fact is that the Indians first came to Kashmir as friends. They said they were our supporters. They told us that we had the right to decide about our future.

I told the Pakistani audience that India has done terrible things to us. But I said that I wanted to know if Pakistan also had a hidden agenda. I asked: “Would you also like to take us over and occupy our land?”

I explained the reason why I was raising this question. Vajpayee had recently made a proposal for establishing a ceasefire and beginning a dialogue. It was our view that it was the people of Kashmir who must come up with their own response. As far as the militants who have come to Kashmir from Pakistan and elsewhere are concerned, they are our sympathisers. They are welcome so long as they have come to help us. But they must not take up the role of ‘owners’ of our movement. I asked: “Would those of you who are supporting them also like to occupy us?” This was probably the first time a Kashmiri leader ever went to Pakistan and clearly had his say.

When I raised this point with Musharraf, he also agreed that they should not have issued such statements from Pakistan.

Q: So you do not have a clear impression whether Musharraf is open or not to the “third option”?

A: I did not discuss it directly with him. We spent more than an hour and a half together. He was interested in discussing Vajpayee’s announcement and whether India was open to a genuine dialogue. I think it is unfortunate that Musharraf came to power as a military dictator. Taking all things into consideration, I think that if the Indians cooperate, Musharraf is still the best man on the Pakistani side with whom the Indians can deal on Kashmir. He is a practical man. He can reach a settlement on Kashmir.

If the APHC had been allowed to go to Pakistan, it would have served as a catalyst. The greatest catalyst for peace could have been the Hurriyat. The Hurriyat could have gone and told the Pakistanis so many plain things. But the Indians take for granted that the Hurriyat are surrogates of Pakistan.

There is substantial evidence that the Hurriyat leaders are not sold on Pakistan’s thinking. However, the Indians are themselves trapped by rigid thinking. We, in the APHC, could have gone to Pakistan and argued with Musharraf saying that the third option is a way out. If the Pakistanis are going to go for a solution that is not commensurate with their known stand, they will need the support of the Kashmiri people. The support will be readily available if they move toward another option.

Q: Would Syed Ali Shah Geelani [a member of the APHC executive and an important figure of the Jamaat-i-Islami of Kashmir] have accepted this?

A: Geelani has his own views. I will express my own views. He is not in a position to deter me. And I am not in a position to deter him.

Q: What does the future hold for Kashmir?

A: I am convinced that it is not only our struggle which will help us achieve our goal. We need also to increase international awareness of our situation. But, first and foremost, the Indian people need to be educated in order to know exactly what is happening in Kashmir. These are the two key constituencies we need to convince in order to ultimately persuade the Indian government to agree to a just solution.

I personally have been to Patna, Delhi, West Bengal, Bombay, and Gujarat. Unfortunately, so far we have had a limited response. We describe the terrible human rights violations occuring in Kashmir. The Indian human rights organisations that have organised our visits have limited resources. There has been a great deal of disinformation about Kashmir by the Indian government. Recently, there has been some openness in the Indian press. However, for the last ten years, the Indian press has shut its eyes and ears to the indiscriminate killing in Kashmir, and has essentially put forward the government’s version.

The standard view among India’s older generation is that there was a dispute over Kashmir that was taken to the United Nations by the Indian government. Now, a new generation has come up. What they believe is that there is an “integral part” of India called Kashmir, populated by Muslims, and that the Muslim countries want to take it away from India. They simply don’t know the basics regarding the historical background. They don’t understand that there is a legitimate dispute about the Kashmir issue.

When the BJP came to power, there were possibilities. We hoped that before the summit with Musharraf, they could open the way toward progress. Instead, Vajpayee and Jaswant Singh issued statements declaring that Kashmir was an “integral part” of India. Vajpayee said this is not an issue to be discussed.

Last winter, Vajpayee said that as Prime Minister he would not traverse the same “beaten path” in Kashmir. We thought something new might be possible. But he has taken the same “beaten path” as all the others. They are rogues. You can’t expect anything from these people.

Q: And what of the Pakistanis? Have they also let you down?

A: They have definitely let us down. What moral support have they given us? The Americans have taken a stand and they have religiously followed it. They have said that in any bilateral talks between India and Pakistan the discussions should take note of the sentiments and views of the people of Kashmir. What’s wrong with Pakistanis? Why shouldn’t they say it? There is a movement going on in Kashmir. The Kashmiris are suffering. If India is not ready to talk with the Kashmiris, then Pakistan should be able to say that we will talk with the Kashmiris and take note of their views.

But Pakistan follows its own national interest. Kashmiris can be sacrificed. Their sentiments can be sacrificed. Similar is the case with India. They say there is no need to talk to the Hurriyat or the Kashmiri people. Day by day, alienation is piled upon alienation.

India’s leadership is committing a great blunder. India is suffering. Indians are losing everything of value. They once valued Gandhi as a great prophet of peace and non-violence. You can see what kind of peace and non-violence they are practising in Kashmir. India has the possibility to emerge as a world power. Kashmir stands in its way.

Q: While travelling in Kashmir, one often hears the comment that despite being an articulate and important Kashmiri voice, the Hurriyat has so far failed to sufficiently broaden its political base among crucial Kashmiri minorities. If “freedom” comes to Kashmir, will it be an equal freedom for Kashmir’s Muslim community and Kashmir’s minorities? Is the Hurriyat a sufficiently representative body adequate to represent a broad spectrum of Kashmiris?

A: Why not? Concerning the present stage, we are in the midst of the struggle. Hindus may not support the Hurriyat at this stage because some people who support accession to Pakistan are part of the APHC. So, at present they have not joined us. We have said, “Well, don’t join us.” Let us get something and then we will discuss the problem. Of course, we will have to broaden our base.

You must examine the attitude of the Indians. What is the dispute here? There are only two parties to the dispute. On one side there is the APHC that says that Kashmir is a disputed territory. The APHC says there is no finality to the “accession,” Kashmir is not “an integral part of India.” On the other side is the Indian government that says: “Kashmir is an integral part of India and accession is final.”

Despite differences within some parties, all the principal political parties in India share the view of the government of India on this issue. The APHC reflects the view of the main political forces in Kashmir that differ with India on these crucial questions. Therefore, the APHC and the government of India are the two main parties that face each other. So, if there is to be a dialogue to narrow down the differences or to find a solution, it must be the Hurriyat and the government of India that enter into discussions.

Once the government of India sits with the Hurriyat, they can certainly raise the question of representation. They can say we are willing to discuss Kashmir with you but there are problems that need to be addressed. You don’t represent Kashmiri Pandits. You don’t represent Jammu’s Dogras. You don’t represent Buddhists of Ladakh. These problems will be addressed and they will be solved.

There are two recognised states involved in the Kashmir dispute — India and Pakistan. The “third party” involved are the people of Jammu and Kashmir. Whatever settlement is ultimately reached, it will be accomplished by agreement. The future status of Kashmir should be decided by agreement of all the three parties. For example, one thing that can be agreed by all is that Kashmir will be a “secular state.” Another matter that can be part of an agreement is that there should be proper representation of all communities in Kashmir with constitutional guarantees. Matters such as these should be settled by agreement. We do not want only one community deciding. A constitutional agreement must come first.

Q: You have often expressed your concern regarding the state of “secular politics” in Kashmir. However, there are elements within the Hurriyat who are publicly on record saying that they are opposed to the idea of a secular Kashmir state. Are there ways that a consensus can be reached so that a possible catastrophe can be avoided in Kashmir?

A: Yes, there are ways. The opinions you refer to are individual views. You may want to quote Mr. Geelani. He is an individual. His party, the Jamaat, is not with him on this matter.

There are two branches of “secularism.” One is European secularism. That is not only anti-Islam, it is also anti-religion. There is also the branch of secularism found in India. The origin of Indian secularism is linked with the events of 1947.

The Indian state faced a problem. The Congress leaders came to the conclusion that unlike Pakistan they needed a state where there would be no restrictions on any religious movement, and that the Indian state should not own any religion. This was a correct decision. And that decision defined Indian secularism. They believe in diversity. Everyone is free to practice any religion.

Q: What would Kashmiri secularism be?

A: It would be the same! Everyone will be free to profess their own religion