Highway to Hell

By Naziha Syed Ali | News & Politics | Published 23 years ago

Abdul Bhatti, who earns his living as a bus driver, has lived for over three decades in Sher Shah, a settlement along the banks of the Lyari river in Karachi.

His cramped, 120 square yard dwelling was home to two families of 10 people. One day last month, at 8 a.m., a brusque announcement was made over a loudspeaker, ordering all residents of the area to vacate their homes within the hour. Demolition teams, reinforced by the rangers, police, and two truckloads of army personnel, stood by to begin the task of clearing the area. Resistance was met with shelling and lathi-charge from which even the women were not spared.

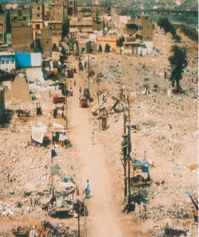

Today Abdul Bhatti’s house is a mound of rubble, as are the rest of the single- and double-storeyed buildings on Sher Shah’s Akber Road. In one place, remnants of a charpoy poke out of the chunks of concrete, a dusty slipper lies in another, testimony to the hasty departure of the occupants. Alongwith the flotsam and jetsam of daily life, dingy little tea stalls and paan shops that supplemented meagre incomes have also been swept aside.

The residents of this low-income colony, a majority of whom are employed in the city’s recycling industry and as daily wage labour, have since been running from pillar to post, trying to find alternate accomodation for their family members, particularly the women. Some have taken up temporary residence with their relatives elsewhere in the city; others have moved into rented premises, an expense they can scarcely afford. A few have had no choice but to spend nights under makeshift shelters in the open. In the process of this upheaval, some have lost their jobs.

There are individuals who have suffered heart attacks from the shock of the swift and brutal demolitions. A 13-year-old boy lost his life last month when he was buried underneath falling rubble.

Over 200,000 people are destined to be dispossessed of their homes in the largest eviction in Karachi’s history, a human tragedy that has been billed by the local government as the biggest anti-encroachment drive ever carried out in the city.

The cause of the misery of so many: the construction of the Lyari Expressway. Their compensation: 50,000 rupees and an 80 square yard plot in areas on the city fringes, devoid of roads, water, electricity and gas.

The Lyari Expressway was initially proposed in the Karachi master plan of 1985 and, in 1992, detailed plans were drawn up for its implementation. But it is only now, under the military government, that the project has been taken up in earnest. However, while in the original plan, the Expressway was designed as an elevated road over the river itself, it is now to be constructed along both banks of the Lyari river, an exercise that entails the disruption of entire populations in the numerous settlements located along its proposed route and the destruction of the physical, social and economic infrastructure built up over the decades.

Sobia Khatoon has four daughters and one son. Widowed 20 years ago when her youngest was just an infant, she toiled as a cleaning woman at several houses to support herself and her children. When her daughters grew older, they worked as seamstresses. Over the years, Sobia Khatoon and her children painstakingly put together their savings and converted the katcha dwelling they initially lived in, on land that had been bought by her husband in Sher Shah colony, into a proper building. Then they had the first storey built, and later added a second one. With two floors rented out, while the widow occupied the third herself, it seemed that the years of hard labour had paid off. However, her house is one of those marked for demolition, which has so far only been prevented by a stay order from the Sindh High Court. “We have taken shelter in a rented house,” says Sobia Khatoon, “but this has reduced us to penury once again. The eviction is a death knell for us.”

According to estimates by the Lyari Nadi Welfare Association, which includes 46 Lyari community groups, 25,400 houses, 3,600 commercial units, 58 places of worship, 38 clinics, 10 schools and one hospital will be demolished in the exercise of constructing the Lyari Expressway. The reclaimed land, estimated to measure 1.8 million square yards, is worth about 20 billion rupees. Opponents of the project, which is to cost five billion rupees, believe that the land remaining after the construction of the expressway and its associated infrastructure, contrary to claims that it will be given over to the construction of parks, will be gobbled up at throwaway rates by land grabbers and developers who will proceed to construct high-rise apartments and shopping complexes on it.

It is contended by some that this is the real purpose of the project and that the highway will not materialise at all. Says Younus Baloch, director, Urban Resource Centre (URC), “The Lyari Expressway is simply not feasible. The government does not have the kind of money needed to build it. The government was going to get a 10 billion rupee loan approved from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for the Northern Bypass but that project was whittled down to one costing 2.7 billion rupees by reducing its width and removing the fencing. The government proposed that the remaining 7.3 billion rupees be diverted to the Lyari Expressway, but the bank refused because no resettlement plan for the evictees had been worked out which is an essential pre-condition for approval.”

The principal reason for the construction of the Lyari Expressway is ostensibly to provide a shortcut for heavy traffic to and from the port. The National Highway Authority (NHA) has stated that once it is constructed, 30,000 vehicles will ply on the 16.5 kilometre road. However, this will exacerbate environmental pollution in already the most congested areas of Karachi; its proposed route defies the current practice of diverting heavy traffic from expressways passing through city limits, such as has been implemented in Riyadh, Bangkok and Boston. Needless to say, no environmental impact assessment (EIA) has been undertaken in the case of the Lyari Expressway as required by the Pakistan Environmental Protection Act 1997. Opponents of the project point out that the Northern Bypass, which was initially proposed as an alternative to the Lyari Expressway, is already under construction, and will better serve as a conduit for heavy traffic.

The design of the Expressway has also been decried for its impracticality. At 12 points along its length of 16.5 kilometres, it will rise to 50 feet from an elevation of 20 feet to enable it to ‘fly over’ existing bridges. The ensuing result has been likened to that of a rollercoaster, which will place a strain on the vehicles plying on the Expressway, further causing them to emit pollutants into the air.

The design of the Expressway has also been decried for its impracticality. At 12 points along its length of 16.5 kilometres, it will rise to 50 feet from an elevation of 20 feet to enable it to ‘fly over’ existing bridges. The ensuing result has been likened to that of a rollercoaster, which will place a strain on the vehicles plying on the Expressway, further causing them to emit pollutants into the air.

Interestingly, detailed plans of the Expressway have not yet been made public and concerned NGOs and associations have been provided with only a satellite map of the area with digitised lines marking the proposed route. This, and the arbitrariness evident in the planned reclamation of land has further fuelled the belief that the project is pandering largely to the nexus between politicians, bureaucrats and land-grabbers/developers.

It has been pointed out that at Sher Shah, a short distance from its starting point , the width between the northbound and southbound lanes on either side of the river is to be 860 feet whereas at Sohrab Goth, where the Expressway terminates, the width between the two narrows to 460 feet. The reason given for this is that flood waters will require a wider passage downstream. However, it seems that some construction, that too in the river bed, has been deliberately spared. One of the examples cited is that of a block of apartments owned by members of the Aga Khan community. Some areas, as well as certain godowns, are believed to have secured their continued existence in return for hefty bribes paid by the residents to the concerned authorities. As a result, to compensate the project design for leaving some construction untouched, large swathes of land on the opposite bank, inhabited since many decades, have been earmarked for demolition. Evidently, the plan is still in a fluid state; residents in several localities have alleged that the original design did not require their eviction, but that their areas were added later.

Official sources maintain that the evictions are also necessary in order to remove encroachments below the flood line. However, only 50 per cent of the designated areas are in the danger zone, while the rest constitute pre-Partition settlements and erstwhile katchi abadis which have since been regularised, where property is consequently eligible for lease, and has been leased in many instances. Even the danger zone does not pose much of a threat any longer; the last flood was in 1977 in which about 250 people living along the Lyari river bed perished. Since then, a trunk sewer, built as part of the Greater Karachi Sewerage Plan, absorbs much of the excess rain water.

Another reason cited for the construction of the Expressway is that it will be an aesthetic addition to the city. This view has been promoted in official presentations with transparencies of boats sailing down the Lyari river and people strolling along its pedestrian walkways with pet dogs. A greater misrepresentation of facts can scarcely be imagined. The Lyari river, as far back as anyone can recall, is a sewage channel, and the proposed Expressway is unlikely to ever resemble the Lahore Canal Road, to which it is being compared.

Hasan Aulia village, one of the oldest settlements of Karachi which traces its existence back to at least 125 years, is also included in the demolition plan. Most of its residents are Baloch, and many of them have lived here for generations since their forefathers were granted the land during the British raj.

Says Jan Mohammed, “We are the founders of Karachi; the colonial style construction on M.A. Jinnah road was undertaken by our ancestors. Many of them also worked on construction projects in Bombay and Delhi.”

Gulnaz Baloch, a doughty old woman with grizzled hair and the belligerent air of a pugilist, firmly announces that she will not allow the eviction to take place. “My family has lived here since time immemorial. I have seen Gandhi and Nehru with my own eyes. The Quaid’s grave was dug by my neighbour. Call the BBC; tell them to interview me. I’ll tell them all about what is being planned for us,” she says, beating her breast.

Hasan Aulia village is one of the settlements where the demolition teams have met with the most resistance. Angry crowds of both men and women have blocked their path, refusing to surrender. A considerable amount of the construction here includes multi-storey buildings, the fruit of years of hard work in the Middle East, particularly from the 1970s onwards.

Mohammed Iqbal’s family has lived in Hasan Aulia since seven generations. His father and brothers work as labourers and drivers in Doha and Qatar. Their under-construction, three-storey house in Hasan Aulia has beige marble floors. The view from the roof includes the ancient Mewa Shah graveyard, where some of the tombstones date back to 1750. Mohammed Iqbal says that officials have claimed that the graveyard will be spared. However, it is rumoured that a fatwa in support of levelling the graves has been obtained and that some graves are indeed falling within the demolition limits.

The inhabitants of the settlement also include low-income families, whose women are employed as sweepresses and washerwomen. When a group of mediapersons and NGO activists arrived on a visit to the locality, several women gathered around, clamouring to be heard. Several of them wept incessantly; the constant, heart-breaking refrain was: “Where shall we go? What will become of us? We don’t know of any other place we can call home…”

Their despair and anguish over the evictions has been exacerbated by the fact, repeated ad nauseam through Karachi’s history, though never on such a large scale, that no proper resettlement plans have been put in place before the evictions have started. While the Land Acquisition Act allows the government to reclaim any leased or notified land, it specifies a certain procedure to be followed before such reclamation. A gazette notification must be published to the effect and made available to the settlements that are to be acquired. A public hearing on the issue is required to be held. Finally, the affected people are to be given as compensation, the market value of the acquired land in addition to any loss of livelihood that would ensue as a result.

While these legal requirements have been blatantly violated, the 200,000 plus evictees have been promised 80 square yard plots, regardless of the size of the property reclaimed for the Expressway project and the number of families living there, and 50,000 rupees for construction. The plots are located in Baldia Town, Taiser Town and Hawkesbay, but sources say that in the first two areas, they have yet to even be demarcated. Thus, many of the yellow allotment papers given to the evictees are vague in the extreme and do not specify the sectors or plot numbers. In Hawkesbay, three kilometres away from the main road, 675 plots have been demarcated and 22 families have begun building their homes there, apprehensive that any delay may result in their allotted plot being taken over by unscrupulous speculators or other claimants. Water, costing 50 rupees a drum despite its brackish taste, is transported to the site by donkey cart. The Baldia Town site is also situated about three kilometres from the nearest main road, the RCD highway. Taiser Town meanwhile, belongs to the board of revenue which has yet to transfer it. It is estimated that the land required for resettlement is about 600 acres. According to a paper written by the URC, “these alternative sites have no water, roads, sewage, electricity, social amenities or job opportunities…experience tells us that it requires Karachi’s development authorities anything between five to ten years to fully develop 600 acres.”

The people evicted from Karachi’s Lines Area ten years ago in the course of the Lines Area Redevelopment Project were also given allotment papers, or parchis as they are known, similar to those in the Lyari Expressway case. Many of them have yet to obtain their plots. In fact, even those who sustained losses in the Lyari river flood in 1977 have still to be given the land that was promised to them.

“What will happen in all likelihood is that government officials will persuade disillusioned allotees to sell them the parchis for a few thousand rupees,” says URC’s Younus Baloch. “One government official may collect several such land allotment papers. During the course of time, the papers will be altered to show him as the allotee. When the resettlement area is finally developed, he will become a millionaire overnight. Some government officials have used this tactic since the ’70s and become property tycoons. The same fraud was perpetuated on the Lines Area allotees as well.”

According to an authority on katchi abadis, “The preparation of the relocation sites should have begun in July last year. Poor people need everything where they are living because of transport costs. Temporary shelters, a sort of transit camp, should have been provided where there should have been a site office for registration. When relocating people, it’s important that there is a host population with a similar socio-economic status in the near vicinity, so the relocated people can use their facilities such as clinics, schools, mosques and madrassas, until they build up their own. You can’t just fling people out into the wilderness.”

However, most of the evictees it seems, will not have to contend with such a situation, for they have been disqualified from obtaining even this “compensation”. The government has rigorously but selectively applied the Land Acquisition Act which denies compensation to illegal commercial outlets. In several places, residential quarters with an adjoining illegal commercial outlet were deemed commercial as a whole and refused compensation. On some occasions, even leased commercial outlets were designated illegal.

Even among the 700 buildings demolished so far that have been classified as residential quarters, the occupants of only 200 have been given parchis and cheques. Some cheques have been rejected by the concerned bank on account of discrepancies in the payees’ names, an obstacle that has at times been rectified by bribing bank officials. Several residents allege that they have had to grease the palms of corrupt city government officials to get compensation in the first place. As a government official himself admits, “There are many stakeholders in this project.”

After having been placed on the back burner for several years, the construction of the highway, scheduled for completion in three years, is being pushed through with unseemly haste. The demolitions were to be completed within the first three months of this year. Their progress has only been impeded by stay orders obtained by residents from the court, and objections by NGOs and community associations.

There seems to be something rotten in the Lyari Expressway project, and this time, the stench is not just wafting up from the river.