Disastrous Winds of Change?

By Afia Salam | News & Politics | Pakistan Floods 2010 | Published 15 years ago

Looking at the scale of destruction the floods have brought in their wake, would you even have believed that we have a ‘functioning’ Federal Flood Commission (FFC) in place since 1976? One-fifth of the country has been ravaged by the raging torrents, despite the fact that the FFC had been allocated Rs 88 billion over the years to control these very floods. So what has this commission been doing for the last 34 years?

Who will hold the organisation accountable, read out the charge sheet, identify neglect, wilful or otherwise, and punish the guilty? Who, indeed, as even while the flood waters are raging, people in responsible positions are adroitly moving out of the organisation. One example is its chief engineer, who is now a member of the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and also its chief spokesperson.

Formed by Z.A. Bhutto after the disastrous 1976 floods, the FFC was mandated with the preparation of National Flood Protection Plans and their implementation, flood forecasting and research to use flood waters for multipurpose benefits.

Where are those plans and where are the benefits? Even the ‘bachao bunds’ (safety embankments) could notbachao (save) the people living alongside them.

Many people are asking similar questions about the NDMA, whose management, or lack of it, is visible from Gilgit-Baltistan to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, down to the flooded plains of Sindh and Punjab.

Firefighting is never management. Management means being up to snuff where disaster risk reduction is concerned; it means paying heed to the Met advisories about the onset of monsoons — although there too one can’t help but point a finger as the forecast for the end of July was a ‘normal monsoon.’ We all know how normal it turned out to be.

However, to its credit, the Met department started alerting the authorities well in advance about the angry skies, but what were the FFC and NDMA doing? Why are the flood affectees saying that they got just a few hours notice to grab whatever they could and evacuate. Why weren’t the evacuations planned, rescue centres set up, rations stocked and medics deployed? But these are questions for another day because for now the priorities have per force shifted to the survival of the millions of displaced.

However, one question remains: Why has the calamity struck this region in particular? Is it climate change, bad luck, bad management, or a bit of all of the above? We need answers to these questions before we can embark on a damage assessment mission from an environmental or ecological point of view.

Most of the experts Newsline spoke to say that while the monsoon downpour was extraordinary, the damage was mostly human-induced. Messing with nature has its consequences, and we have invoked the wrath of the mighty Indus which is fed up of being twisted, turned and engineered out of its natural course and, hence, has come charging down to claim what was its own.

Environmentalists have been crying hoarse about the perils of deforestation in the mountainous north of the country, in Gilgit-Baltistan as well as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The pull of gravity turns the rivers into raging torrents, but when they are offered no resistance by way of a vegetative cover, they sweep away all that comes in their path. The rocks and boulders resting on the soft alluvial soils dislodge and become lethal projectiles.

A senior environment expert, with decades of experience in areas around KP and FATA, says that this time, the scale of damage magnified due to the mismanagement of land in KP more than deforestation which, officially, has been banned for over 20 years. It started as a natural calamity when more rain fell in one week than does in an entire season. According to him, KP’s stream system does not have the capacity to handle so much run off. A vegetative cover could have helped to an extent, but not a lot, given the amount of water in the rivers and streams.

A senior environment expert, with decades of experience in areas around KP and FATA, says that this time, the scale of damage magnified due to the mismanagement of land in KP more than deforestation which, officially, has been banned for over 20 years. It started as a natural calamity when more rain fell in one week than does in an entire season. According to him, KP’s stream system does not have the capacity to handle so much run off. A vegetative cover could have helped to an extent, but not a lot, given the amount of water in the rivers and streams.

He blames the avarice of the land-grabbers, citing examples of hotels that were built almost midstream, constricting the channel. Now imagine what will happen if water that used to flow over a 200-metre wide bed is limited to 50 metres or even less. There will be more pressure and more depth resulting in stronger currents, meaning the water will have more strength to wash away anything that obstructs its flow. And with about 290mm of rain in 24 hours and no water passage, the result was obvious.

Whatever happened to the flood protection projects undertaken by the FFC? Under the Annual Development Plan, in two different projects, Rs 27.3 million and Rs 26 million were spent in district Nowshera in the years 2007-08 and 2008-09. The question is, what kind of projects were they that they failed to protect so abysmally?

These questions need answers. As far as a solution to the problem is concerned, in the words of the environmentalists, land zoning must be adhered to. This means that land must be used for its proper purpose; forests must remain as such, flood plains must not be encroached upon, etc. This is a recurrent theme throughout the new narrative that questions the reasons for the scale of disaster and looks for a way forward.

It becomes all the more imperative when we try to look at it through the prism of climate change. Most experts are cautious in attributing the floods to climate change, but this is a debate that is not going to go away.

Dr Daanish Mustafa, professor of Geography at Kings College, London, says that even if these floods were not directly a result of climate change, one cannot ignore the fact that there have been many such peaks in precipitation in the last decade, whereas earlier, such peaks used to occur decades apart.

In an article, Dr Pervaiz Amir, a leading environmental and agricultural expert, said that these extreme events tie in with the scientific predictions of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) and Monsoon Asia Project that showed global warming rising at unprecedented levels, and floods and droughts haunting South Asia, especially Pakistan (see interview).

Dr Jay Gulledge, senior scientist and director of the Science and Impacts Programme at the Pew Centre on Global Climate Change, in his article for Pew Research, joins the dots between the raging fires in Russia and the floods in Pakistan. He points to the fact that the earth temperatures are the highest in recorded history. He also points out that such extreme weather events have become more frequent over the past half century.

Explaining the connection between the Russian fires and Pakistani floods, he says, “At the most basic level, more droughts and heat waves are expected because of hotter, longer-lasting high-pressure systems that dry out the land, as witnessed in Russia. On the other hand, more floods are expected because hotter air evaporates more water from the surface and holds more moisture. When the conditions are right, that moisture is released, creating a deluge, as witnessed in Pakistan.”

This analysis is corroborated by CNN meteorologist Brandon Miller and Weather Underground meteorologist Dr Jeff Masters. The findings cited by Dr Gulledge in his Pew Research article indicate that the Russian heat wave is associated with an intense dome of high atmospheric pressure that has settled in over Eastern Europe. This dome is so immovable that it is blocking the flow of the jet stream, which typically determines where mid-latitude storms drop their rains.

The block over Russia forced the jet stream to dive far southward, carrying with it a great deal of moisture that normally would have watered Russia’s substantial wheat crop. Instead, that rain fell in northern Pakistan, adding to the already abundant rainfall normally associated with the Asian monsoon this time of the year. The combination of the two was lethal, so while Russia’s crops withered and burned, Pakistan’s crops drowned.

And there’s more. Adil Najam, director of the Frederick S. Pardee Centre for the Study of the Longer-Range Future and professor of International Relations, and Geography and Environment at Boston University, who has also co-authored the IPCC report that won Al Gore the Nobel Prize, maintains that, “It would be premature to say whether these floods have anything to do directly with climate change or not, but they are a good reminder for all of us of why we should be thinking of climate change — and fast. The rains are clearly a natural phenomenon. But there is nothing natural about the death and destruction these rains have brought. That is all human-manufactured. Our arrogant policies that have disregarded the ecological integrity of the natural systems we depend upon have magnified the fury of the torrents that have been sweeping across Pakistan. Deforestation in the north has robbed nature of its natural barriers and bad urban planning has turned streets in Nowshera and elsewhere into torrential rivers. Whether climate change brings havoc at this horrific scale or not, it will make our climate more unpredictable and uneven.”

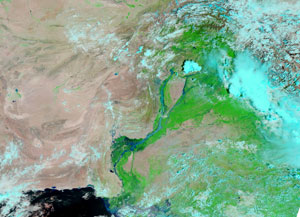

So much for laying the blame at Mother Nature’s doors. We come back to human interference, which is the reason why one-fifth of our country is under water, more than 1,600 people have lost their lives due to floods and scores are dying due to the disease and starvation that has followed. The infrastructure, especially in the northern part of the country is not just in a shambles, it is almost non-existent, with roads, bridges, telecommunication and electricity towers washed away, along with homes, hopes and livelihoods.

Related articles:

A freelance journalist, with an experience of print, electronic and web media. She writes, and trains media on climate change, gender and labour issues, as well as media ethics.