Apocalypse Now

By Sairah Irshad Khan | News & Politics | Pakistan Floods 2010 | Published 15 years ago

The imagery is Biblical. Like the Great Flood, the mighty Indus has swept in its flow life, land, crop, hope. But this time there has been no atonement for sin. That survives. It is embodied in some of the landlords of Sindh and Punjab and the people’s ‘elected representatives’ who prepare to reap their harvests from fields ploughed by the wretched of the earth, whose trust — and the embankments that protected their paltry holdings — they have breached, to save their own vast land expanses.

Sin thrives in the profiteers who hoard foodstuff and medicine, waiting to sell when desperation dictates the price. And it resides in members of the administration and clerics in Southern Punjab who refused to shelter Ahmedi families fleeing the waters. In fact, Christians have been denied help in Punjab and Sindh, as have the Dalits in Sindh.

The destruction wrought by the floods may take years to fully assess, but increasingly evident are graphic indicators of more deep-rooted devastation: the floods have stripped bare and exposed on camera, in print and in living colour the ugly face of a feudal-sardari system and its umbilical connect with politics and bureaucracy that have together created and fostered an underclass so wretched, it has nothing left to lose.

The destruction wrought by the floods may take years to fully assess, but increasingly evident are graphic indicators of more deep-rooted devastation: the floods have stripped bare and exposed on camera, in print and in living colour the ugly face of a feudal-sardari system and its umbilical connect with politics and bureaucracy that have together created and fostered an underclass so wretched, it has nothing left to lose.

Those “dirty, unwashed masses” the river has thrown up were not rendered naked and starving by a few hours in the water. Nor did those irises in the lustreless eyes of children and teenagers turn yellow and rheumy on account of the floods. For many who fled the onslaught, there was nothing to leave behind.

Floods 2010 is a story that has its genesis in the beginning of Pakistan time. It has unmasked almost seven decades of abandonment by the state and exploitation by feudal overlords of a beleaguered populace. And as the tale has unravelled, so too has the country.

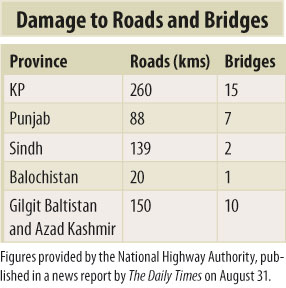

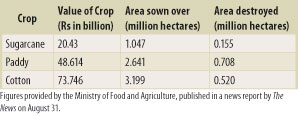

Which province has been the hardest hit in this catastrophe — deemed the worst in living memory — is moot. According to official estimates, more than 20 million people have been directly affected and of these, 3.5 million are children at high risk of death through disease. The UN has rated the displacement of people as the biggest diaspora since Partition. And the national loss in terms of infrastructure is incalculable. But as the waters ebb in the north and continue to rage in the south and batter Sindh, it is likely to be the biggest victim. Even before the floodwaters reached Thatta and Sujawal, damage to the infrastructure in the province was estimated at 700 billion rupees — and counting. The loss to human life and livestock remains to be fully assessed — though by August 31, the Federal Flood Commission already stated that 129,416 heads of cattle had perished in Sindh. But even a cursory glance at the montage of images emanating from the interior will bolster the claim by Dawn on August 19 that “Sindh [is] the hardest hit province.”

There is the vast migration. Tens of thousands of men, women and children, many of them barefoot and naked, marching like the living dead, to an uncertain future, the expression on their faces betraying ‘the end of imagination,’ of hope… Equal numbers hunched under the open sky clutching terminally ill children and waiting for redemption… Still others in tented ‘relief’ camps, in some of which food, faeces and flies mingle, as do the refugees and the precious livestock they have managed to salvage. Given the sanitation — or lack thereof — disease spreads like wildfire. And as the dust settles in these camps, so also do the differences between the tribes that inhabit them. Tribal divides do not for bonhomie make. How that plays out in the longer term, remains to be seen.

There is the vast migration. Tens of thousands of men, women and children, many of them barefoot and naked, marching like the living dead, to an uncertain future, the expression on their faces betraying ‘the end of imagination,’ of hope… Equal numbers hunched under the open sky clutching terminally ill children and waiting for redemption… Still others in tented ‘relief’ camps, in some of which food, faeces and flies mingle, as do the refugees and the precious livestock they have managed to salvage. Given the sanitation — or lack thereof — disease spreads like wildfire. And as the dust settles in these camps, so also do the differences between the tribes that inhabit them. Tribal divides do not for bonhomie make. How that plays out in the longer term, remains to be seen.

The roads that have survived the onslaught see ragged encampments springing up along their sides. Strewn in between these are the bloated carcasses of cattle. Some of these creatures drowned before they could find higher ground to take refuge. Others died of heart attacks. In Sindh, cattle are never bound. As their owners confined them in order to get them onto boats or life rafts, many bolted in an attempt to free themselves. Unused to, in their quiet pace of life, such frenzy, their hearts just gave away. Now their rotting corpses provide fodder for scavengers — vultures, crows, flies.

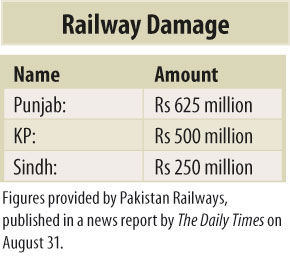

It will take a long time to rebuild the province’s destroyed homes, roads and railway tracks. It might take even longer to get the educational institutions fully operational. Academic programmes in schools and colleges across interior Sindh have been halted for four months by official decree. Many of the buildings have been requisitioned by the local administration as camps for the displaced. Thus hundreds of families used to the open are now forced to huddle together in cramped confines and cook, wash, eat and defecate in these premises — an invitation for disease.

Ironically, the flood has managed to achieve — at least in the short term — what no number of human rights initiatives could. Although women in Sindh have always been active workers in the fields and at home, while their men tend to idle way their hours in chaikhanas, the former have technically remained in purdah. And a deeply entrenched cultural tradition often combined with vested interest (property, revenge) has rendered women vulnerable through the ages to that most heinous of crimes: karo kari or “honour” killing.

Ironically, the flood has managed to achieve — at least in the short term — what no number of human rights initiatives could. Although women in Sindh have always been active workers in the fields and at home, while their men tend to idle way their hours in chaikhanas, the former have technically remained in purdah. And a deeply entrenched cultural tradition often combined with vested interest (property, revenge) has rendered women vulnerable through the ages to that most heinous of crimes: karo kari or “honour” killing.

The Great Flood has shorn Sindh — even if temporarily — of all such contrived modesty. Women, often clad in “immodest” rags are now forced to share quarters with strange men. And many of them — whose spouses have left in an attempt to make their way home to assess the situation there — have been compelled to take the initiative to procure food for their children, fodder for their livestock and medicine, in a completely non-segregated environment.

There are other elements the river has thrown up. The ‘dakoos’ and ‘dharels’ — Sindh’s infamous highwaymen — have been forced to flee their riverine hideouts. They have made their way into the relief camps. Given the lean pickings there, chances are they will head to the cities along with the cavalcade of landless peasants who have nowhere else to go. These are desperate brigands who know no other life but that of crime. That does not augur well for the cities they make their way to.

But, perhaps, even more disturbing is the bigger picture that will emerge après le deluge.

But, perhaps, even more disturbing is the bigger picture that will emerge après le deluge.

Those flood affectees who left land behind — no matter how small their holdings — will go home. But what home is, no one knows. The waters have washed away all markings, destroyed boundaries. The whole system of mapping and division of property will have to begin anew. New feuds will inevitably erupt, and the patwaris will make hay.

Furthermore, there is the state of the land the refugees will return to. The ‘fertile soil’ envisaged after the waters recede is, in fact, salt-laden and uncultivable. It will take at least two years before this land can be farmed — and that too providing there is timely and appropriate intervention in the form of corrective measures by the government, the waderas in the area or the people’s ‘elected’ reps — the latter two often being one and the same. Without treatment, the land will remain fallow. Meanwhile, who will feed the millions who depend on it in the interim?

And who will feed the millions that do not go home — those haris who have nothing to go back to. “We are free,” said one. “Free from our wadero, from the shackles we have been bound with and our fathers and grandfathers before us. We will never go back.” And there are others who would want to go back but can’t. There were thousands of Sindhis living along the banks of the Indus on government land. Many of them were told to take and settle these riverine areas by local landowners. And so they did. For 10, 20, 30 years, poor families claimed a small tract of parched land, worked it and made a home. Now, they are homeless, driven away by impossible waves that have washed away all evidence of their life’s toil. They have no papers, no deeds to show the land as theirs. They are left with nothing and have no claim to anything.

And who will feed the millions that do not go home — those haris who have nothing to go back to. “We are free,” said one. “Free from our wadero, from the shackles we have been bound with and our fathers and grandfathers before us. We will never go back.” And there are others who would want to go back but can’t. There were thousands of Sindhis living along the banks of the Indus on government land. Many of them were told to take and settle these riverine areas by local landowners. And so they did. For 10, 20, 30 years, poor families claimed a small tract of parched land, worked it and made a home. Now, they are homeless, driven away by impossible waves that have washed away all evidence of their life’s toil. They have no papers, no deeds to show the land as theirs. They are left with nothing and have no claim to anything.

Their migration to the cities will inevitably change the demographics of the country quite dramatically. It will not help the infrastructure in cities already choking for want of modernisation and expansion to meet the needs of an ever-growing population. The fallout could be dangerous. As Karachi has witnessed, as new groups move in, new mafias emerge, pitting ethnic communities against one another. Add Sindhis to the existing volatile Pathan-mohajir imbroglio in Karachi, and it is almost sure to combust. The MQM is certainly cognisant of this fact, throwing its resources into preventing migration to the urban centres it controls.

Fuelling anxieties about the future are the concerns repeatedly expressed by western commentators. By filling the void created by an absent or impotent administration to provide relief to the victims of the terrible flood, will extremist organisations also win their hearts and minds?

It is certainly worth considering. Throughout the country perhaps the best organised and most flush camps are those set up by Islamist fundamentalist groups. Many of these are undoubtedly genuine relief and welfare organisations with only their stated humanitarian aims propelling them. However, there are other more sinister reports — of banned militant outfits financing and running camps throughout the land and in the process sowing the seeds of indoctrination in the minds of children they house, feed and clothe.

In Sindh. Photos: Afzal Ahmed Shaikh

The only remedy then will be the response of Pakistan’s civil society to the ongoing crisis and all it leaves in its wake. There is no denying the immense contribution of the private sector to the myriad crises that have come the country’s way. The onus for relief has always been squarely laid on its shoulder throughout Pakistan’s existence by successive governments riddled with apathy, corruption and mismanagement, and the private sector has delivered.

This time, too, there are signs of hope: in the unstinting, overwhelming generosity of rich and poor alike to private aid agencies (government relief organisations have understandably garnered little given the trust deficit). There is hope in the thousands of students who line city streets under the blazing sun across the country collecting donations from passersby for flood relief. There is hope in the numerous relief and welfare bodies that have sprung into being and into action, manned by conscientious, hard-working individuals.

There is hope also in the palpable anger of those directly affected by the crisis and those who who are no longer willing to sit on the sidelines and allow the powers-that-be to get away once again with murder by sins of omission and commission.

Perhaps in the floods there has been a cleansing of sorts.

Related articles:

Flood of Sorrow by Talib Qizilbash

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is a region that has suffered through years of turmoil: suicide bombings, Taliban rule, military operations and displacement. The floods are just the latest blow. But how much can its denizens take?Who’s to Blame? by Abdul Wahab

Official inaction and haste to secure agricultural land in Balochistan has drowned cities and rendered millions homeless.Religious Mission or Political Ambition? by Shahzada Irfan Ahmed and Ayesha Siddiqa

With their well-organised relief efforts, the religious and militants outfits pose the threat of making significant inroads in the flood-affected regions.Disastrous Winds of Change? by Afia Salam

Are the floods in Pakistan a result of climate change or are they human-induced?Technology to the Rescue by Sana Saleem

ICT and social media tools are being used to map and garner support for individual relief efforts.