You Win Some, You Lose Some

By Mahir Ali | News & Politics | Published 19 years ago

As 2006 faded into the past, George W. Bush seemed to be in a pensive mood. He acknowledged that the most powerful nation in the world was not winning the war in Iraq, a realisation that appears to have dawned on the US president after his Republican Party was trounced in November’s congressional elections, ceding control of the House of Representatives, as well as the Senate, to the Democrats. But, Bush added, it was not losing either. A few days later, he announced that the US was going to win. He didn’t say when. Or how.

As 2006 faded into the past, George W. Bush seemed to be in a pensive mood. He acknowledged that the most powerful nation in the world was not winning the war in Iraq, a realisation that appears to have dawned on the US president after his Republican Party was trounced in November’s congressional elections, ceding control of the House of Representatives, as well as the Senate, to the Democrats. But, Bush added, it was not losing either. A few days later, he announced that the US was going to win. He didn’t say when. Or how.

Since the elections, Bush has been under pressure to come up with a new plan for Iraq, given that the current strategy has failed abysmally, but it appears that all the advice he has received from a variety of sources — including the Iraq Study Group comprised supposedly of wise old men, and the Pentagon — has only added to his confusion. The likeliest outcome of his deliberations will be a surge of about 30,000 in US occupation forces — the idea being to “secure” Baghdad, a city where dozens of corpses are discovered every day and where gunmen are audacious enough to kidnap public servants en masse from their ministerial workplaces.

The November results were the consequence of a steadily growing recognition, at long last, among the American electorate that the casus belli for the Iraq war consisted almost exclusively of lies, and that the toppled regime, however vile it may have been, posed no threat to the US. The outcome compelled Bush to bid farewell to his equally delusional defence secretary, Donald Rumsfeld, who has been replaced by an old CIA hand, Robert Gates. It also meant the end of the road for Bush’s offensive ambassador to the United Nations, John Bolton, who lost all hope of congressional ratification.

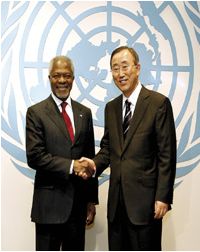

His exit coincided with the end of Kofi Annan’ s term as UN secretary-general. The latter, whose efforts at impartiality did not impress Washington, conceded long ago that the conquest of Iraq was illegitimate under international law. On his way out, he remained diplomatic, but became a little less reticent about speaking his mind, directing a belated blast at the egregious human rights abuses that are such a crucial component of the “war on terror.” It will be highly surprising if similar sentiments ever escape the lips of his successor, South Korea’s foreign minister Ban Ki-moon.

s term as UN secretary-general. The latter, whose efforts at impartiality did not impress Washington, conceded long ago that the conquest of Iraq was illegitimate under international law. On his way out, he remained diplomatic, but became a little less reticent about speaking his mind, directing a belated blast at the egregious human rights abuses that are such a crucial component of the “war on terror.” It will be highly surprising if similar sentiments ever escape the lips of his successor, South Korea’s foreign minister Ban Ki-moon.

The UN may eventually be called upon to play a central role in Iraq: hopefully, it won’t agree to lend its imprimatur to any scheme that does not involve a complete withdrawal by the US-led axis. For much of the past year, parts of Iraq have been mired in a sort of civil war between Sunnis and Shias, while the struggle against the occupation has simultaneously picked up pace. The concluding months of 2006 were among the deadliest in terms of Iraqi civilian as well as US military casualties since April 2003. Earlier in the year, a relatively meticulous survey came up with 655,000 as a median figure for Iraq’s war dead, and the toll continues to mount each passing day. The occupation forces are not involved in some of the violence, but there is no escaping the fact that it is taking place in circumstances created by gratuitous aggression.

Elections, followed by months of negotiations, finally led to a Baghdad government headed by the appropriately morose-looking Nouri Al Maliki, with Jalal Talabani as the president. But they came with strings attached. The perception of puppetry is also an issue for Afghanistan’s relatively long-serving Hamid Karzai, although perhaps not the biggest one. His country represented the “good war”: one that the US and its allies did not seriously doubt they could win. Until this year, when a Taliban resurgence in the southern provinces took them by surprise, leading to some of the fiercest fighting Afghanistan has suffered since October 2001. Karzai seldom loses an opportunity to blame his nation’s troubles on Pakistan’s failure to curb infiltration by terrorists (with Nato officers often concurring), as a result of which his relations with General Pervez Musharraf remain testy despite a conciliatory meal hosted at the White House by their mutual benefactor.

Between the two war zones lies Iran, which reacted defiantly last month to the imposition of sanctions by the UN on account of its nuclear ambitions. Perhaps a more significant blow for Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was the elections to the municipal councils and the Assembly of Experts, in which conservative hardliners allied to the president took a whacking. They were preceded by reports of anti-Ahmadinejad protests by students. The Iranian leader’s sporadic threats against Israel were followed by an audacious gimmick: an international conference on the Holocaust that was widely seen as a provocative attempt to raise questions about the Nazi judeocide via a gathering that inevitably attracted all manner of anti-Semites.

Among the Iraq Study Group’s more sensible suggestions was the idea of an American dialogue with Iran and Syria as a means of bringing some semblance of order to the region. Bush categorically rejected the idea, which is a pity not only in the context of Iraq but also that of Lebanon, where Hezbollah reputedly depends on Damascus and Tehran for resources and advice. Hezbollah’s stock rose exponentially after a border incident in which it captured a couple of Israeli soldiers. The event led to a full-fledged invasion of Lebanon, with the US and Britain backing the Israeli aggression, which included the bombardment of civilian targets and caused more than 1,000 deaths; only a small proportion of the victims were Hezbollah members or associates.

Israel’s failure, for the first time, to humble an Arab adversary served to embolden Hezbollah, which has lately been involved in an apparent bid for power in Lebanon, alongside its allies. The assassination of Pierre Gemayel, a minister belonging to the country’s most prominent Maronite Christian family, queered the pitch somewhat, but the government of Fouad Siniora remained embattled as the year faded.

Across the border, Israel’s prime minister Ehud Olmert faced calls for his resignation over the Lebanon fiasco. But he stuck it out, continued his battle against Palestinians, and eventually came up with a device for dividing them. His first summit late last month with the Palestinian Authority’s president Mahmoud Abbas was preceded by a dangerous rise in intra-Palestinian strife, pitting Abbas’s Fatah faction against Hamas, which caused a sensation by winning elections a year ago. Abbas, under Israeli, American and British pressure, plans to seek fresh elections, evidently as a means of dislodging Hamas. The latter, not surprisingly, is up in arms. Hamas has thusfar refused to acknowledge Israel’s right to exist: that’s unwise and impractical, but hardly constitutes sufficient grounds for early elections. If elections are held and boycotted by Hamas, that will rob the results of any legitimacy. If Hamas does participate, what if it wins again? Watch out for interesting developments on the Palestinian front in the next few months, but don’t count on any miracles.

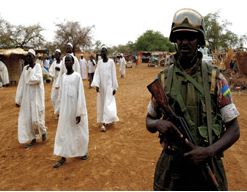

If a miracle is particularly called for, it is in Sudan’s Darfur region, where an apparent genocide has been in progress since 2003 at an estimated cost of 200,000 lives, with pro-government Janjaweed militias decimating local tribes. Last month, Annan expressed the hope that Khartoum would accept a joint UN-African Union peace-keeping force. The African Union, meanwhile, appeared to be supporting Ethiopia’s crusade against Islamist forces in Somalia, who evidently posed a threat to the transitional government in that country after occupying Mogadishu in the middle of 2006. The US sees the Islamists as terrorists, although reports suggest they are by no means a monolithic bunch. Besides, even Somalis who have no sympathy for the Islamists resent the Ethiopian intervention, and the unfolding crisis could yet spiral into a full-fledged war in one of Africa’s most benighted regions. On a more hopeful note, Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf became Africa’s first elected female leader when she was sworn in as the president of Liberia.

If a miracle is particularly called for, it is in Sudan’s Darfur region, where an apparent genocide has been in progress since 2003 at an estimated cost of 200,000 lives, with pro-government Janjaweed militias decimating local tribes. Last month, Annan expressed the hope that Khartoum would accept a joint UN-African Union peace-keeping force. The African Union, meanwhile, appeared to be supporting Ethiopia’s crusade against Islamist forces in Somalia, who evidently posed a threat to the transitional government in that country after occupying Mogadishu in the middle of 2006. The US sees the Islamists as terrorists, although reports suggest they are by no means a monolithic bunch. Besides, even Somalis who have no sympathy for the Islamists resent the Ethiopian intervention, and the unfolding crisis could yet spiral into a full-fledged war in one of Africa’s most benighted regions. On a more hopeful note, Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf became Africa’s first elected female leader when she was sworn in as the president of Liberia.

The threat of rekindled hostilities also lurked in Sri Lanka, where terrorist attacks and increasingly belligerent rhetoric from the Tamil Tigers pointed towards further bouts of bloodshed on that idyllic isle. Fortunately, the trend up in the Himalayas was refreshingly different: popular protests led to the restoration of democracy by a shaky King Gyanendra, and the government of Giriji Prasad Koirala thereafter concluded a deal with Prachanda, the leader of the Maoist guerrillas who control large swaths of the Nepalese countryside, on elections this year for an assembly that will decide whether the world’s only Hindu kingdom will be converted into a republic.

Elsewhere in Asia, a military coup toppled Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, and elections are expected in the second half of 2007. In East Timor, it took more unusual means to dislodge prime minister Mari Alkatiri, who apparently proved too radical and independent for the liking of Washington and Canberra: intervention by Australian forces. But there was no intervention of any kind in North Korea, which claimed to have tested a nuclear weapon. A compromise resolution on sanctions got through the UN Security Council, but no explicit threats were made against Pyongyang. Instead, there was pressure on China to talk Kim Jong-il out of it. Many analysts pointed to the risk that Japan, with its new nationalist prime minister Shinzo Abe at the helm, may opt once more for the militarist path, overcoming popular resistance to developing the sort of weapons that obliterated Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The signs in Latin America were considerably less ominous. If the re-election of Alvaro Uribe in Colombia brought some solace to Bush, that’s about the only development that could be characterised as such. The rest of the continent was dominated by a trend towards the left. Symbolically, perhaps the most significant success was that of Michelle Bachelet, the doctor and single mother who was elected president of Chile last January: three decades earlier, she had been a victim of the US-supported coup led by General Augusto Pinochet, whose brutal regime lasted for 17 years, after which he remained the army chief for a further eight years. He died last month and, thankfully, was denied a state funeral.

In other elections, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva retained the Brazilian presidency, and Hugo Chavez won a third term in Venezuela by a veritable landslide. Chavez had caused a sensation at the UN in September by implying that Bush was the devil, but his occasionally over-the-top rhetoric doesn’t detract from the fact that his transformation of Venezuela through judicious expenditure of its oil wealth is establishing a trend that deserves to be emulated throughout the Third World. Chavez is also constantly pushing for closer Latin American integration, following in the footsteps of his idol Simon Bolivar. He also looks upon Fidel Castro as a mentor. And if the Cuban leader, who handed over power to his brother Raul after falling ill in August, is indeed dying, he at least has the satisfaction of knowing that the seeds he sowed nearly six decades ago are at last bearing fruit.

Chavez’s closest allies in the neighbourhood are Evo Morales, an indigenous activist who was sworn in as Bolivia’s president a year ago, and Ecuador’s president-elect Rafael Correa. But he doesn’t face much hostility even from moderate social-democrats such as Lula, Argentina’s Nestor Kirchner and Peru’s newly elected Alan Garcia, who last ruled the country in the 1980s. As did Oscar Arias and Daniel Ortega, who staged comebacks in Ecuador and Nicaragua respectively. If Mexico bucked the leftward trend, its proximity to the US may have played a role: although Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador was within half a point of the ostensible victor, Felipe Calderon, the electoral authorities resisted popular pressure for a complete recount, a decision that could corrode Calderon’s legitimacy.

In faraway Britain, Tony Blair’s legitimacy was corroded not by contested election results but by his more or less unquestioning subservience to Washington over Iraq and Lebanon, not to mention an unfolding sleaze scandal that involved titles being granted to punters who were prepared to cough up donations for the Labour Party’s coffers. Under heavy pressure from the public and his own party, Blair eventually announced that he would step aside this year, presumably after completing 10 years at No.10 Downing Street — a record for a Labour prime minister, albeit not one of which the party should be particularly proud. A terror scare mid-year prompted by a tip-off from Pakistan led to a heightened alert and scores of arrests — but, as usual, little further information, spurring suspicions that it was yet another triumph of hype over hard facts.

Across the Channel, Jacques Chirac’s popularity plummeted further in the wake of an attempt to alter employment laws, which was aborted by protests the likes of which France hadn’t seen since 1968. Chirac’s term expires this year, and he may be replaced by the country’s first female head of state in 200 years: the Socialist Party has adopted as its candidate the charismatic, conservative Segolene Royal.

Protests also erupted in Hungary after prime minister Ferenc Gyurcsany’s comments to the effect that his party had lied to win elections. In this case, the unrest was compared to the events of 50 years ago, when Hungarians bravely, if briefly, stood up to Moscow. In the event, Gyurcsany survived. Poland, meanwhile was host to a phenomenon never witnessed during the communist era: when Jaroslaw Kaczynski was named prime minister in July, he was indistinguishable from the president. The latter, elected the previous year, is called Lech Kaczynski. Yes, they are related. Yes, they are siblings. But wait, there’s more: they are identical twins.

Protests also erupted in Hungary after prime minister Ferenc Gyurcsany’s comments to the effect that his party had lied to win elections. In this case, the unrest was compared to the events of 50 years ago, when Hungarians bravely, if briefly, stood up to Moscow. In the event, Gyurcsany survived. Poland, meanwhile was host to a phenomenon never witnessed during the communist era: when Jaroslaw Kaczynski was named prime minister in July, he was indistinguishable from the president. The latter, elected the previous year, is called Lech Kaczynski. Yes, they are related. Yes, they are siblings. But wait, there’s more: they are identical twins.

Whether or not Poland stands for peace, it certainly favours brotherhood. Which is, perhaps, more than one can say about Russia, where, under Vladimir Putin, power has steadily been passing into the hands of former members of the KGB and its successor, the FSB. However, at least one ex-FSB agent wasn’t so lucky: Alexander Litvinenko, based in Britain for the past six years, died a slow and pitiful death after being poisoned with polonium-210. On his deathbed, the lethally radioactive man pointed an accusatory finger at Putin. But there are various other possibilities, and no conclusive evidence has thus far emerged. One thing Litvinenko does leave behind is the mystery of the year. At the the time he was taken ill, he was reportedly investigating the murder in Moscow by more conventional means a couple of months earlier of the crusading journalist Anna Politkovskaya, who was gunned down in the lift of her apartment block after years of threats. Politkovskaya was a specialist on human rights abuses in Chechnya. Putin eventually ordered an investigation into her assassination, but no one will be surprised if the results are never made public.

There is no shortage in this world of bitter and twisted events. At the same time, there are many signs of hope, too. They all tend to be overshadowed by what goes on in Iraq. That’s what happened last year, and 2007 is unlikely to be vastly different. Beyond that, who knows? Human beings are an inventive and resilient species. But, at the same time, our capacity for self-destruction is unmatched.

Mahir Ali is an Australia-based journalist. He writes regularly for several Pakistani publications, including Newsline.