The Minority Report

By Ayela Khan | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 23 years ago

Islam is still the fastest growing religion in North America — an astonishing fact given its negative portrayal by the western media today. In an atmosphere charged with xenophobia, Muslims in the United States have, post September 11, been confronted with escalating degrees of hostile suspicion — not only because of their ‘different’ appearance, but also as a consequence of their beliefs, which to many a westerner are synonymous with extremism and fundamentalism. These notions have been reinforced by a biased American media, who have very often jumped the gun in blaming criminal activities and terrorist attacks on Muslims, sans evidence or trial. Muslims are, in the post September 11 world order, under greater scrutiny than ever before, their “otherness” established and their motives suspect.

Islam is still the fastest growing religion in North America — an astonishing fact given its negative portrayal by the western media today. In an atmosphere charged with xenophobia, Muslims in the United States have, post September 11, been confronted with escalating degrees of hostile suspicion — not only because of their ‘different’ appearance, but also as a consequence of their beliefs, which to many a westerner are synonymous with extremism and fundamentalism. These notions have been reinforced by a biased American media, who have very often jumped the gun in blaming criminal activities and terrorist attacks on Muslims, sans evidence or trial. Muslims are, in the post September 11 world order, under greater scrutiny than ever before, their “otherness” established and their motives suspect.

American Muslims: The New Generation, by Asma Gull Hasan, explores what it is to be a Muslim in America today. Interestingly, this book was written in 2000, and thus speaks of the public mood before Islamophobia had reached its zenith. Anti-Muslim stereotyping, the controversial teachings of Louis Farrakhan who is the founder of the ‘Nation of Islam,’ social problems faced by young Muslims, and the education of second- and third-generation Muslim youth are some of the issues discussed in the book.

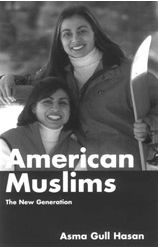

The cover picture of Hasan and her sister, both dressed in ski jackets, defies the conventional typecasting of Muslim women, and projects in its place a more modern image of young, educated adults enjoying a rather western sport! This also conveys, at the very first glance, Hasan’s message that Muslims do not have to look different to be different. The engaging narrative in the first person and numerous personal anecdotes sprinkled throughout the book, lend it an indisputable appeal.

Opening on an informational note, the first chapters are full of facts on the basic tenets of Islam: the Five Pillars, its different sects, social practices and so on. The author goes on to stress the flexibility of Islam, claiming that its very adaptability enables “this religion to stretch and stretch without snapping.” Muslims within America, she informs us, encompass a wide range of nationalities, cultures and professions. Muslims have featured on the Fortune 500, are a diverse group of stockbrokers, bankers, footballers — even rock stars! Hasan uses this to point out the similarities between Islamic and American values: self-respect, an emphasis on family and the importance of education and of independence whilst contributing to society. Yet, Muslims face a very great challenge — the public image of being associated with terrorism. Despite their multiple ethnicities, she urges Muslims to unite in order to make a positive contribution to American society, and thus empower themselves “to take our place alongside other groups as a part of American culture.”

Controversially, Hasan, a self-proclaimed feminist, disagrees with mainstream Muslim thinkers on issues such as covering of the head, gender segregation and dating. Since there are no ulema (group of religious scholars) in America, American Muslims have solved their theological problems from their own perspectives, she reasons, which has resulted in “some immigrant American Muslims becom[ing] more actively and consciously religious than they would have been in their home countries.” Hasan is keen on keeping Muslim theology alive, and thus supports the establishment of Islamic schools all over America which will provide for a solid grounding in Islamic values. Islamic schools make it easier for children to interact with other Muslim children and practice their religion (for example, fasting during Ramadan), in addition to providing them with all the facilities of regular schools.

Interestingly, the author suggests that segregation at Muslim gatherings, particularly in mosques, should be discouraged and young Muslims be given the opportunity to socialize with each other in the company of their respective families. Hasan feels that dating should be permitted so that Muslim girls and boys can meet and get to know each other. If segregation continues young, Muslims will increasingly marry non-Muslims, thus weakening the Islamic social set-up.

In a critique of the American media, she lambasts its irresponsible pursuit of sensationalism which links Islam and Muslims with criminal activities and gives credence to xenophobic ideas. Citing movies such as Executive Decision and True Lies, Hasan exposes the negative stereotyping of Arabs. She also accuses Disney of making several anti-Islam movies, including cartoons such as Aladdin and The Return of Jafar.

Written from the perspective of a modern young girl, born of Pakistani immigrant parents, Hasan defines herself as both American and a practicing Muslim. With topics as diverse as how to cope with problems of discrimination, battling with the “terrorist” label, and how to unite Muslims coming from different countries and cultures into one identity — that of an American — without compromising their Islamic values, this book is sure to appeal to non-Muslims and the younger generation of Muslims alike. Hasan concludes on an optimistic note, hoping that American Muslims will unite and assimilate, and continue to make a positive contribution to their country. However, given the increased scrutiny to which they are now subjected and the virulence of the media after the September 11 terrorist attacks, one wonders if Hasan’s dreams for American Muslims will ever be realised.

No more posts to load