Past Tense?

By Massoud Ansari | News & Politics | Published 23 years ago

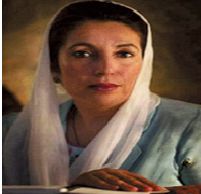

A new debate has been engendered in the country after the country’s election commission rejected Benazir Bhutto’s nomination papers. The grounds offered by the EC for her dismissal are that she has been convicted in absentia by the country’s accountability courts and is hence ineligible to stand for election under the revised electoral laws. Bhutto and her supporters have cried foul not only on account of her disqualification, but because the papers of Nawaz Sharif, whom the anti-terrorist court had sentenced to life imprisonment for ‘hijacking’ a plane and endangering the life of innocent passengers, were accepted. While Nawaz Sharif’s gesture of dropping out of the race ‘in support’ of Bhutto has led to a thaw in the standoff between the two hitherto bitter adversaries, it has also led to an increasingly vocal concert of discontent between the members of the two parties against the current regime. The PPP sees Bhutto’s disqualification as a clear indicator of Musharraf’s desire to permanently oust Bhutto from Pakistani politics.

A new debate has been engendered in the country after the country’s election commission rejected Benazir Bhutto’s nomination papers. The grounds offered by the EC for her dismissal are that she has been convicted in absentia by the country’s accountability courts and is hence ineligible to stand for election under the revised electoral laws. Bhutto and her supporters have cried foul not only on account of her disqualification, but because the papers of Nawaz Sharif, whom the anti-terrorist court had sentenced to life imprisonment for ‘hijacking’ a plane and endangering the life of innocent passengers, were accepted. While Nawaz Sharif’s gesture of dropping out of the race ‘in support’ of Bhutto has led to a thaw in the standoff between the two hitherto bitter adversaries, it has also led to an increasingly vocal concert of discontent between the members of the two parties against the current regime. The PPP sees Bhutto’s disqualification as a clear indicator of Musharraf’s desire to permanently oust Bhutto from Pakistani politics.

“The founding chairman of the PPP, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was murdered by the courts, and now they are politically assassinating his daughter, the party’s current chairperson, Mohtarma Benazir,” says Jamil Soomro, the PPP’s candidate for the provincial assembly seat from Larkana.

The permanent chairperson of the PPP, Bhutto had filed three nomination papers — two for general seats (NA-204, Larkana-1 and NA-207, Larkana-III) and one for a reserved seat for women. Bhutto has contested the elections from NA-207 several times and won from this constituency each time — in 1988, 1990, 1993 and 1996. However, it is for the first time that she has also filed her nomination from NA-204 — the traditional seat from which her ailing mother, Begum Nusrat Bhutto, was elected to the National Assembly in the last four elections. Nusrat Bhutto is not contesting the polls this time. Ghinwa Bhutto, the Lebanese widow of Murtaza Bhutto, was Benazir’s chief opponent from NA-204, but the returning officer rejected her papers since, in his view, her graduation degree from Lebanon was not acceptable. Ghinwa Bhutto, the chairperson of the Shaheed Bhutto faction of the PPP, had submitted a baccalaureate certificate along with her nomination papers, which she claims is equivalent to a Pakistani Bachelors degree; the authorities ruled otherwise.

With both Benazir and Ghinwa out of the running, there will be no participation by any Bhuttos in the polls for the first time since 1970. “When Ms. Bhutto’s PPP chose to stay away from the 1985 partyless elections under Ziaul Haq it became a sham poll. This time, although her party is participating in the polls, the government’s decision to disqualify her will not lend any respectability to the elections,” says a political analyst.

Bhutto, who chose self-exile after she lost the 1997 elections following her government’s dismissal in 1996, had been signalling to her party cadres that she would soon be returning to the country to face the charges against her. “I’m not scared of going to jail or to face trials, but I will come only at the right time,” she said in a message to party workers recently.

According to party insiders, Bhutto’s decision to return was made when she called for a meeting of the party high command in Dubai, who advised her to return to the country if her nomination papers for the elections were accepted. She was reportedly told, “The military government is all set to put you behind bars once you land in the country, but if you return it will breathe new life into the party, and you will sweep the elections.” The party leaders maintained that if Benazir returned, neither the present government nor any future one would be able to keep her behind bars for very long.

Party sources maintain that if her nomination papers had been accepted, Bhutto would have returned to the country the next day. However, since they have been rejected, the chances of her returning to the country to lead her party’s election campaign are slim. “If she chooses to stay out of the country, which now seems quite likely, it would mean the establishment has succeeded to some extent in its strategy to show that the PPP is not necessarily synonymous with the Bhuttos,” says a party member.

Benazir Bhutto, who entered the political arena after her father was hung by Zia-ul-Haq on April 4, 1979, has seen both, the heights of public support and glory — when she fought against the military dictator — and the depths of ignominy, when her popularity plummeted to its lowest ebb after her brother was killed during her second stint in power following which she was removed from office on charges of corruption and incompetence.

When Benazir Bhutto chose to fight General Zia’s dictatorial regime and avenge her father’s death, Bhuttai ja dushman asaan gholai gholai mareendaaseen, (we will find the enemies of Bhutto and kill them) became the war cry in Sindh. “Akailee nihathi larki” (a girl unarmed and alone), was how she was perceived and generally referred to after the renowned poet, Habib Jalib wrote a detailed poem on her struggle against the army dictator. In those days, many in the country followed her call and opted to fight alongside her. Several of them paid a heavy price. Some were hanged on phony charges, countless numbers were publicly lashed for supporting Bhutto, and others were thrown into jails across the country. Yet they persevered and remained steadfast in their support.

A collective sigh of relief was audible when General Zia died in a plane crash in 1988. Bhutto was subsequently elected Prime Minister in the general elections which followed the General’s death. “It was a miracle, a dream come true. We didn’t believe it would ever happen,” recalls one of her political workers.

It was a heady time for all those who had rendered huge sacrifices for Bhutto. But the bubble was soon to burst. Rampant corruption and indifferent governance led to the Bhutto government’s dismissal by the then President, Ghulam Ishaq Khan, within one-and-a-half years of acquiring power. Her husband, Asif Zardari was largely credited with her downfall, having earned himself during this period the sobriquet: ‘Mr. 10 per cent.’

Bhutto returned to power in the 1993 elections, but it was a repeat performance. It seemed like deja vu when her government was once again, dismissed by her own former loyalist, President Leghari, in 1996, on charges similar to those levelled by Ghulam Ishaq. “We can exonerate her for her poor showing during her first stint on account of her inexperience. But she was given a second chance to change the destiny of the people and the country, and seemed to have learnt nothing from her mistakes. There was even more corruption the second time around, with her notorious spouse part of every deal that involved money,” says Ghulam Hyder, an old, disgruntled political worker.

Her former supporters contend that even if the establishment manipulated Bhutto’s ouster on both occasions, as she continues to claim, she fell into their trap because of her own shortcomings. “Had she not been corrupt and compromised on principles, she could still have fought her way back and would have been with us today,” says Dr. Ayaz Memon, a former student activist from Nawabshah.

As matters stand, Bhutto is a long way from home, and if the current dispensation has its way, that’s where she will remain for the forseeable future.