The Art of Politics

By Salwat Ali | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 18 years ago

The current Jamal Shah exhibition, ‘Situations,’ at Canvas is more an appendage to his previous collection of paintings shown under the title of ‘Lovers and Unlawful Combatants,’ than a radically new body of work. A self-confessed rebel, Shah critiques existing reality. Using the language of pop or conceptual art, he engages directly with political subjects, commenting on everything from the failures of the current administration to discriminatory politics and the protest movement, and historical as well as current events.

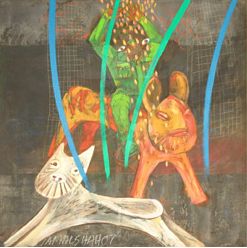

An amalgamation of abstraction and figuration, Shah’s art, as always, is loaded with symbolism. Adept at distorting to enhance the shock value of his art, he surprisingly opts for partial clarity in this collection to further emphasise the human condition. A few of his forms are brutally dismembered, but most are clearly visible as political victims or as perpetrators. The saluting uniformed figures directly reference the current regime, satirising the thorny territory of contemporary politics, while the trampled, trapped and beheaded figures stand in for innocent humanity. Complex and riddled with innuendoes, the works do not reveal themselves at first glance as the artist focuses on several aspects simultaneously. His compositions are a gutsy mix of primal living and political rage. Using contradictory references of mourning and joy, pleasure-seeking and punishing, he alludes to our turbulent and confusing socio-political climate. By suggesting the formal and the raunchy, he nudges the onlooker to review the ‘situations’ in the light of not just how and what is perpetrated but also its aftermath. Indicating the instigators of terrorism, crackdowns, state disappearances killings and missing persons, he also paints the other side of the coin — the castigated, suffering and bereaved humanity. The repeated use of terracotta artifacts, mythical horned creatures and extinct animals speak of the imagery of ancient civilisations. Is Shah referring to the pottery finds of Mehargarh to draw attention to the political ‘situation’ in Balochistan? Viewed in this light the works take on sinister meanings, provoking one to reflect on the much publicised army operations going on in the region.

An amalgamation of abstraction and figuration, Shah’s art, as always, is loaded with symbolism. Adept at distorting to enhance the shock value of his art, he surprisingly opts for partial clarity in this collection to further emphasise the human condition. A few of his forms are brutally dismembered, but most are clearly visible as political victims or as perpetrators. The saluting uniformed figures directly reference the current regime, satirising the thorny territory of contemporary politics, while the trampled, trapped and beheaded figures stand in for innocent humanity. Complex and riddled with innuendoes, the works do not reveal themselves at first glance as the artist focuses on several aspects simultaneously. His compositions are a gutsy mix of primal living and political rage. Using contradictory references of mourning and joy, pleasure-seeking and punishing, he alludes to our turbulent and confusing socio-political climate. By suggesting the formal and the raunchy, he nudges the onlooker to review the ‘situations’ in the light of not just how and what is perpetrated but also its aftermath. Indicating the instigators of terrorism, crackdowns, state disappearances killings and missing persons, he also paints the other side of the coin — the castigated, suffering and bereaved humanity. The repeated use of terracotta artifacts, mythical horned creatures and extinct animals speak of the imagery of ancient civilisations. Is Shah referring to the pottery finds of Mehargarh to draw attention to the political ‘situation’ in Balochistan? Viewed in this light the works take on sinister meanings, provoking one to reflect on the much publicised army operations going on in the region.

Jamal Shah draws much from the gestural jauntiness of the abstract expressionists. His picture-making and brushwork are flamboyant, wild and raw, which may account for his rudimentary imagery and generous use of slashes and stripes, webbed grids, and showers of pellets, rain (or is it teardrops?) to animate the compositions. Likewise, his chromatic choices are very earthy and primary. Varied shades of ochre and terracotta, punctuated by sharp greens, reds and yellows, mimic the colours of advertising, cartoons and folk art.

Jamal Shah draws much from the gestural jauntiness of the abstract expressionists. His picture-making and brushwork are flamboyant, wild and raw, which may account for his rudimentary imagery and generous use of slashes and stripes, webbed grids, and showers of pellets, rain (or is it teardrops?) to animate the compositions. Likewise, his chromatic choices are very earthy and primary. Varied shades of ochre and terracotta, punctuated by sharp greens, reds and yellows, mimic the colours of advertising, cartoons and folk art.

The art is disturbing and the artist’s intention to challenge viewer perception is well directed. Shah has always drawn attention to issues and violations of human rights, especially with regard to regional marginalisation.His complex, intertwined content appears volatile and suggestive, and it needs to be unravelled through slow engagement. And it is that eureka moment that is the true worth of the painting — it brings coherence to an otherwise apparently chaotic whirl of objects and subjects.