Imperialism Unmasked

By I. A. Rehman | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 21 years ago

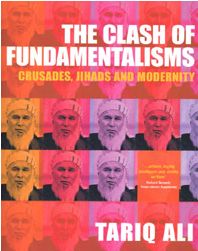

Tariq Ali’s The Clash of Fundamentalisms should be compulsory reading for anyone who wishes to understand the phenomenon of the Muslim peoples’ decline and the depredations caused by the latest version of predatory imperialism. As one who has stayed at the barricades even after the barricades have fallen, Ali is brutally frank in pouring out his scorn on the imbecile and the servile, and wants to lead his readers out of false notions of modernity and the culture of obedience to might. The subject is vast, covers continents and hundreds of years of history. The host of themes addressed cannot get more than a capsule lecture each. Generalisations thus become unavoidable. Further, Tariq Ali is uneasy in the cloister of an academic though quite capable of being one. His frequent forays into journalism in the first person constitute a calculated risk that he is prepared to take in order to raise his credibility as a witness to history.

Tariq Ali’s The Clash of Fundamentalisms should be compulsory reading for anyone who wishes to understand the phenomenon of the Muslim peoples’ decline and the depredations caused by the latest version of predatory imperialism. As one who has stayed at the barricades even after the barricades have fallen, Ali is brutally frank in pouring out his scorn on the imbecile and the servile, and wants to lead his readers out of false notions of modernity and the culture of obedience to might. The subject is vast, covers continents and hundreds of years of history. The host of themes addressed cannot get more than a capsule lecture each. Generalisations thus become unavoidable. Further, Tariq Ali is uneasy in the cloister of an academic though quite capable of being one. His frequent forays into journalism in the first person constitute a calculated risk that he is prepared to take in order to raise his credibility as a witness to history.

The purpose of the exercise is simply stated: “In the clash between a religious fundamentalism — itself the product of modernity — and an imperial fundamentalism determined to ‘discipline the world’, it is necessary to oppose both and create a space in the world of Islam and the West in which freedom of thought and imagination can be defended without fear of prosecution or death.” The target audience comprises Muslims and the US establishment, both of whom can be faulted for their rage and self-righteousness.

The volume begins with a fairly long discussion on the origins of Islam and the tussles between priests and heretics, written in the western idiom, which may not be palatable to some Muslims. Ali defends his right to criticise belief in the ‘Letter to a Young Muslim.’ After pointing out that Blair, Bush and Osama invariably invoke the protection of the Almighty, he says: “All three have the right to do so, just as I have the right to remain committed to most of the values of the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment attacked religion — Christianity mainly — for two reasons: that it was a set of ideological delusions, and that it was a system of institutional oppression, with immense powers of persecution and intolerance. Why, then, should I abstain from religious criticism?”

While Tariq Ali is quite sure of the non-religious underpinning of the west’s (mainly American) fundamentalism, he is not quite clear about the Islamic revivalists’ roots in religion, as he concedes that the Muslim peoples do not constitute a monolithic bloc. However, he is convinced of the Muslim societies’ need for reformation: “The rise of religion is partially explained by the lack of any other alternative to the universal regime of neo-liberalism. Here you will discover that as long as Islamist governments open their countries to global penetration, they will be permitted to do what they want in the socio-political realm.

“The American Empire used Islam before and it can do so again. Here lies the challenge. We are in desperate need of an Islamic Reformation that sweeps away the crazed conservatism and backwardness of the fundamentalists but, more than that, opens up the world of Islam to new ideas which are seen to be more advanced than what is currently on offer from the west.”

The idea of an Islamic Reformation has figured in the writings of both Islamic scholars and European Orientalists for centuries. On this point, Tariq Ali confines himself to the role of a political analyst in a historical context. However, the discourse has to move further, beginning with an analysis of the works of a whole series of scholars in different Muslim countries, including Iqbal, and a thorough appreciation of where they were right and where they stumbled and, above all, the reasons for their ineffectiveness.

The author’s prescription that “this (Reformation) would necessitate a rigid separation of state and mosque; the dissolution of the clergy; the assertion by Muslim intellectuals of their right to interpret the texts that are the collective property of Islamic culture as a whole; the freedom to think freely and rationally and the freedom of imagination,” is good as a motto but leaves the prickly issues of the required effort unanswered.

The main body of the volume is a racy account of the travails of the Arabs and the plight of the people of South Asia. Its account of impact on human lives of the unfinished stories of Afghanistan and Kashmir, and militarisation of Pakistan’s politics, economy and social life is a useful refresher course. Many in Pakistan will find in the chapters on Indonesia and Malaysia the essential clues to an understanding of the ways of imperialism. One feels that the chapter ‘A short course history of US Imperialism’ is strong on history and not so detailed on contemporary machinations.

Two sources of Tariq Ali’s strength are his access to the global storehouse of information, including information that is often not available to the oppressed, and his ability to cull from the writings of poets and novelists the essential features of the human condition that are not observed by either historians or politicians.

Mr. I.A. Rehman is a writer and activist living in Pakistan. He is the secretary general of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan Secretariat.