A Room with a View

By Talib Qizilbash | Arts & Culture | Published 16 years ago

When the lights dim for The Dictator’s Wife, a 1980s video of the American party-rock band, The Cosmopolitans, lights up the backdrop. “Shape up shape up/Firm up firm up / Tone up tone up / With Debbie,” squeak the female singers as they jump around. It’s both bemusing and amusing. Callisthenics-infused go-go dancing is not the first thing that comes to mind when hearing the play’s title. Then again, this play is scripted by Mohammed Hanif, and satire — a C-130 Hercules amount of it — should be expected.

The point of the pop-punk dance tune in Hanif’s latest analysis of dictator-dom is foggy at first. But the eureka moment occurs when the chorus kicks in: “How to keep your husband happy.”

The life-long efforts of this dictator’s wife to keep her husband happy seem to be appreciated. For it’s their 34th wedding anniversary, and she has just received 5,000 roses from her lawfully wedded autocrat.

But she’s disdainful of the gesture. Much has already tainted the relationship, and this wife is a very angry and bitter one. Her man may have risen to be the 7th most powerful person in the world but his ranking as husband falls considerably lower down. Besides forgetting previous, and bigger, marital milestones, he’s taken to hiding in the bathroom and brings a briefcase that contains active controls for his country’s nuclear arsenal to bed with him each night. It’s competition she detests on many levels.

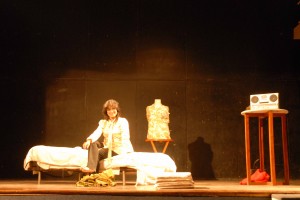

Hanif and his wife, Nimra Bucha (who has done both stage and radio plays), put up productions ofThe Dictator’s Wife in the UK last year. The NCA presentation in Lahore on April 17, in which Bucha directs and stars, was the Pakistan premiere of the one-woman show (Bucha is hoping to stage shows in Karachi and Islamabad too). While Bucha’s performance is mostly compelling, the character she plays is always intriguing. Mrs Dictator is tightly wound, fiery but only mildly sympathetic. She has a killer memory for the wrongs done against her and is articulate about her feelings in a way that only long-harboured anger and constant deliberation allows.

Hanif and his wife, Nimra Bucha (who has done both stage and radio plays), put up productions ofThe Dictator’s Wife in the UK last year. The NCA presentation in Lahore on April 17, in which Bucha directs and stars, was the Pakistan premiere of the one-woman show (Bucha is hoping to stage shows in Karachi and Islamabad too). While Bucha’s performance is mostly compelling, the character she plays is always intriguing. Mrs Dictator is tightly wound, fiery but only mildly sympathetic. She has a killer memory for the wrongs done against her and is articulate about her feelings in a way that only long-harboured anger and constant deliberation allows.

With her 5,000 roses piled up behind her, the title character grumbles about the life her husband has built for them. She rants about his romantic failings, his military training, his power, his relationship with his western paymasters, his saviour complex, his love affair with the media spotlight, his weakness for designer suits, his unpopularity (which has brought years of endless protesting to their doorstep) and his nuclear briefcase. As she moves about the stage, making effective use of simple props that add levity, provide clarity and set mood (a bed, a general’s jacket festooned with medals, army fatigues, radio, tea trolley, a stack of newspapers), her monologue becomes a 50-minute judgement on the dictator. Clearly, his dismal approval ratings have spread from the streets into his own bedroom.

But her hatred is not reserved for him alone. She taunts and chastises the protestors outside, giving them cold nicknames and calling them “beggars with banners.” As the dictator’s spouse who is sworn to secrecy, she is envious of the public’s ability to constantly nag and scream the truth. Of course, she takes no responsibility for her lot in life. She distances herself from the adage “the woman behind the man” and later says, “I didn’t marry him because he was in the army. I wanted someone in the foreign service.” Her story allows both marriage and militarism to be explored. Power and personal responsibility are dealt with in both contexts, as is the issue of legacy.

But her hatred is not reserved for him alone. She taunts and chastises the protestors outside, giving them cold nicknames and calling them “beggars with banners.” As the dictator’s spouse who is sworn to secrecy, she is envious of the public’s ability to constantly nag and scream the truth. Of course, she takes no responsibility for her lot in life. She distances herself from the adage “the woman behind the man” and later says, “I didn’t marry him because he was in the army. I wanted someone in the foreign service.” Her story allows both marriage and militarism to be explored. Power and personal responsibility are dealt with in both contexts, as is the issue of legacy.

But who is this dictator who has regressed into this delusional, paralysed leader? Everyone remains nameless in the play. Hanif’s dictator is more of a composite, with references to both Generals Zia and Musharraf. And while Pakistan is clearly the fertile ground from which this work has sprung, in the play the country remains nameless too.