Unholy Vows

By Zehra Nabi | News & Politics | Published 13 years ago

On April 18, Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry ruled that the three Hindu women who had been converted to Islam, Rinkel Kumari, Dr Lata Kumari and Aasha Kumari, should decide if they want to return to their parents or stay with their new husbands. All three stated that they had willingly converted to Islam and wanted to live with their husbands.

However, there are still concerns about the climate of intimidation in which these cases were carried out and both Rinkel and Dr Lata had previously made contradictory statements in court about their conversions. Often in such cases the Hindu parents and lawmakers receive death threats and therefore raises the question if these decisions by the three women were made under duress. — Zehra Nabi

Imagine your name is Bharti. You are a 15-year-old Hindu girl who lives in a small apartment in Lyari. Your father is a driver and social worker who raises money for others while struggling to pay your family’s medical bills. You have three older brothers, who are busy with their own jobs and families. Your future seems bleak.

Imagine you then meet Abid. He is the son of a police constable and promises to marry you. He promises you many things — but on the condition that you convert to Islam. You agree and run away with him. His family teaches you the Kalima and gives you a niqab to wear. After a few days, they take you to a maulvi. While the nikah form is being filled, you already know what you have to say. You tell the maulvi that you are 18-years-old and your name is now Ayesha.

Imagine that a few months pass. You are still living with Abid and his family. Your father lost the court case after a medical report was produced that stated that you are 18. You couldn’t look your mother in the eye when she came to court. You haven’t once been able to visit your home since you ran away. Your in-laws still haven’t given you a cellphone but sometimes you are able to borrow a phone and briefly talk to your brothers. When you speak to them, you can’t help but cry.

Be it the mean streets of Lyari or the dusty villages of interior Sindh, stories such as these are becoming increasingly common in Pakistan. In the last four months alone there have been at least 47 reported cases of alleged forced conversions of young girls from minority communities. But none of these cases have quite captured the fascination of the public as that of Rinkel Kumari.

Nineteen-year-old Rinkel disappeared from her home in Mirpur Mathelo, a village in the Ghotki district of Sindh, on February 24. The answer to what happened to her varies significantly, depending on whom you speak to. According to her father Nand Lal, a government schoolteacher, Rinkel woke up somewhere between four and five in the morning to go to the bathroom when she was drugged and kidnapped by armed men. She regained consciousness at around nine in the morning to find herself in Barchundi Sharif in Daharaki — a stronghold of PPP MNA Mian Abdul Haq, also known as Mian Mitho, who is the spiritual leader of the shrine where conversions regularly take place. Just hours after her arrival in Barchundi Sharif, Rinkel was forcibly converted to Islam, married off to one of the kidnappers, Naveed Shah, and subsequently renamed Faryal.

Mian Mohammed Aslam, the son of Mian Mitho, provides a different version of events. He stated on an evening news show that Rinkel showed up with Naveed Shah at his doorstep, expressing her wish to convert to Islam and get married. Aslam added that he contacted Rinkel’s parents to let them know his daughter was with him and even invited them to come visit her before she converted, but they never showed up.

And to add to the confusion, there is a third account of events according to which Rinkel was indeed in love with Naveed and went to meet him on the morning of February 24, but did not know that he would be waiting with other men, ready to kidnap her.

In response to the latter accounts, Rinkel’s family has stated that they did not want to meet their daughter at Mian Mohammad Aslam’s residence because they were concerned that they would not be able to talk freely in the presence of the MNA’s son. And her parents have denied suggestions that Rinkel knew Naveed, stating that since there is no phone in their house and Rinkel does not own a cellphone, there was no way for them to have contacted each other.

But be it Rinkel, Bharti or any other girl, the problem at the heart of all these cases is that nobody knows what actually happened to the victims. Some of the girls, including Rinkel, have made somewhat contradictory statements, initially saying that they willingly converted to Islam and later crying that they want to return to their parents. And in all known cases, the accused have fiercely guarded the girls from meeting their families. This raises several questions: Were the girls’ statements made under duress? Should non-Muslim parents be allowed to meet their now Muslim daughters? Does tempting a young girl with false promises count as coercion? Are these forced conversions and marriages essentially cases of rape and sexual harassment committed in the guise of Islam?

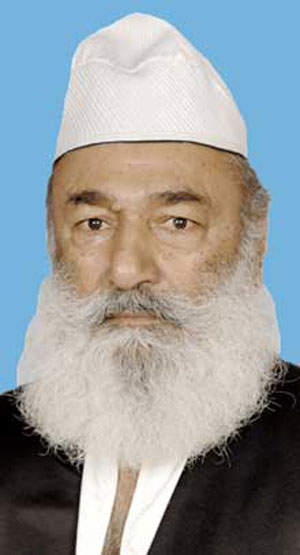

Advocate Iqbal Haider believes the answer to all these questions is an unequivocal yes, and he does not hide his disgust towards Mian Mitho and others involved in such conversions: “Mian Mitho is exploiting his status as an MNA and has been indulging in the most objectionable activities.”

PPP MNA Mian Mitho

Haider has fought many cases of forced conversions and described the kind of problems that commonly arise in such cases. “No police officer would dare defy the orders of an MNA. The police is not independent,” stated Haider, adding, “I recently saw it in court when two police officers led the girl into the courtroom and her alleged husband was glued to her.”

The police was apparently unconcerned that the man was yet to be proven as the husband and that he was imposing his presence on the girl. It was only when Haider shouted at the police that they separated the two. The families are often not allowed anywhere near their daughters and Rinkel’s parents and their supporters have received public death threats from Mian Mitho and his abettors.

It was against this climate of intimidation that the court decided to move Rinkel and Dr Lata, a 29-year-old who also converted and got married in February, to Islamabad. Haider will not be representing any of the cases in the Supreme Court but he believes it was the right decision to move the girls to more neutral territory. “Keep the girls in Islamabad in a protected area but you can’t keep them there forever. I hope the court holds judicial inquiries into each and every case.”

Haider emphasised the importance of cross-examining all the witnesses since the girls’ statements are often made under duress. And he also pointed out the importance of having a liberal judge since, in his words, “There are bigots everywhere.”

Rinkel and Lata had their court hearing in Islamabad on March 26. Rinkel was barely able to speak and it took her two minutes to answer whether she studied science or arts in school. Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudry instructed everybody to leave the court so that he could talk to the girls privately. The girls were then allowed to briefly meet their parents before being sent to Darul-Aman for two weeks, according to the court’s orders.

In a phone conversation the day after the ruling, Rinkel’s father, Nand Lal, revealed that in the few minutes the family spent with Rinkel, she cried non-stop and said that she wanted to return home with them. She also told them that Mian Mitho’s men had threatened her to not make a statement in favour of her family. While her father hopes that Darul-Aman will provide a safe environment for his daughter, the family does fear that Mian Mitho’s men will be able to reach her there as well. If Rinkel is happily married, as Mian Mitho and his followers like to claim, then why do they feel the need to resort to these intimidatory tactics?

PPP MNA Nafisa Shah, who has publicly condemned the forced conversions, believes this environment of intimidation is the main source of the problem. “Coercion does not just mean using brute force,” she said, “We have an extremely claustrophobic environment in which there is space for only one religion.” And it is this claustrophobic environment that limits opportunities for minority communities in the country and makes the offer to convert and get married all the more alluring to young, vulnerable women. Nafisa Shah also pointed out that Hindus are rarely involved in serious crimes in Pakistan, but because they don’t have arms, they become all the more vulnerable to outside threats.

Nafisa Shah did not want to specifically talk about Mian Mitho, but she made it clear that these forced conversions go against the ideology of the PPP and points out that people like Shahbaz Bhatti and Salmaan Taseer lost their lives as a result of speaking up against prejudicial laws. Shah emphasised that the space for dialogue and multi-faith expression is shrinking and attributes Talibanisation as the source of this problem. She also added that conversions are not an issue, but the fact that in Pakistan it is a one-way street of only minorities converting to Islam that causes concern.

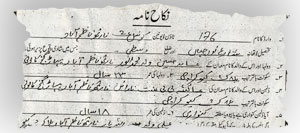

According to Bharti’s nikahnama she is 18-years-old.

Abdul Hai, assistant coordinator at the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, agrees that there is nothing wrong with converting, even if it is for the sole purpose of getting married. “The real problem is where is the girl going?” he adds “Maulvis will say in court that the girl’s parents are kafirs and that she can no longer meet them. How can you forcibly cut the girl off from her parents?”

Senior journalist and human rights activist, Akhtar Baloch reiterates the points made by both Shah and Hai: “You cannot stop adults from converting or getting married. But why is it only the Hindus who are converting to Islam? And that too girls? Why don’t we have men converting to Islam or Muslims converting to other religions?”

Baloch is also concerned that the cases being highlighted in the media are of those who are financially more secure and he fears that there are countless more cases that go ignored.

One such case is that of Bharti. On December 2011, Narain Das found his daughter was missing from home and filed an FIR at the Baghdadi thana only to soon discover that his daughter had run off with Abid, the son of Anwar Kalia who is a constable at Preedy police station.

This is not the first time one of Das’s children ran off to convert to Islam. Around 12 years ago, Das’s employers, car dealers, lured his oldest son Lakshman, who was at the time barely a teenager, to convert to Islam. The men, who Das drove cars for, would send the young boy to fetch alcohol and when Das scolded him, they suggested that he convert so that he would no longer have to live by his parent’s rules. Das and his wife would try to visit Lakshman but each time he would run away. When Das finally got a hold of his son, Lakshman said that he ran away because he was told that if he met his non-Muslim parents they would all become wajib-ul-qatl. Das had enough knowledge of Islam to know this was untrue but as a cautionary measure got a fatwa from a neighbourhood maulvi. When Lakshman was nearly 18, Das proposed to his son’s converters that they should get his son married and help him get started in life. The next day, Das was called to take his son back home.

“I bet nobody in all of Pakistan has done what I did next to my son,” said Das. He went on to relate how he got his son a job with a Muslim butcher and when a Hindu girl fell in love with his son, he told her parents that she would have to convert to Islam since his son is a Muslim.

“I have a Muslim son. I have Muslim grandchildren. And I am the Hindu dada of those children,” Narain said, stating that he has no issue with his daughter converting to Islam. What offends him is that his daughter was lured to run away and that Kalia’s family is preventing them from contacting each other.

Also, Das has NADRA documents stating that Bharti is 15 but the police got a medical report alleging that she is 18, over which Das lost the court case.

Das was visibly furious when I met him. “If these NADRA documents hold no meaning, then close down all their offices in the country. And how can Bharti suddenly be older than her brother Sunny? Next they’ll come and say she’s older than her parents.”

The family has received death threats for pursuing this case and Das added, “The biggest mistake I made was hiring Amarnath Motumal as my lawyer. Not because Amarnath is a bad person, but because he is a Hindu and the other side clearly threatened him.”

Motumal, who is also the vice-chairman of HRCP, confirmed that Bharti is indeed only 15 but the case is now unfortunately closed and he hopes public outcry might lead to a new, fairer trial.

Das revealed how Anwar Kalia had the police on his side. The DIG Sindh ruled that Bharti should be taken to a women’s thana and that Anwar Kalia’s family would not be allowed to visit her there. However, these orders were ignored and Kalia’s family would go take meals to Bharti everyday. He also describes Bharti’s alleged husband (Das and his family do not recognise the marriage since Bharti was under coercion) as a good-for-nothing drunkard and drug addict. Her brothers tell me I can ask anyone in the neighbourhood about Abid’s reputation.

Occasionally her brothers were able to speak to her on the phone and they said she would always cry and say she made a mistake. In trying to get in touch with Bharti, I spoke to Abid’s uncle who firmly advised me to move on and not bother them, saying “Bharti is happily married so there is no point in talking to her.”

He admitted that they medically proved her age but did not want to disclose the name of the hospital or doctor they went to. And the maulvi who presided over the nikah ceremony, Mohammed Abbasi, was of little help as well. When asked how he confirmed Bharti, or rather Ayesha’s age, when she had no form of identification on her, he said, “She said so. And you can tell by looking if someone is 15 or 18.”

He also shamelessly told me how Narain Das spoke to him on the phone for an hour, begging for help, but he did nothing. “I have given my statement to the police and the girl married willingly.” It also does not concern him that the witnesses were only from the boy’s side even though in Islam, witnesses from the bride’s side are required.

“If they didn’t accept me as a witness because I’m Hindu, then why didn’t they take my Muslim son as a witness?” Das asks. “And why is it that Dr Lata who is 29 is taken to a women’s shelter, but my 15-year-old daughter is sent away with the accused? Why should I be dealt a different judgement because I am poor?”

Had Rinkel’s family not been able to find the right contacts, had Mian Mitho not been involved, had the Pakistan Hindu Council not decided to take up the issue, her case too perhaps would have been left ignored.

New cases of forced abductions are emerging every month. But Nafisa Shah is sceptical about giving exact figures because nobody is able to find out for certain if the girl in question converted willingly or not. How can one know when soon after the conversion, the girls are married off and cut off from the public? Even in the rare case in which a girl speaks up, there is fear of persecution. According to Seema Rana, a member of the Hindu community who is doing research on these conversions, a girl from Lyari was asked to take an oath on the Quran in court. She refused, saying that she cannot take the oath since she is a Hindu and was forcibly converted. The girl was returned to her parents, but her family feared the accused might take revenge and immediately got her married. Even though the girl is willing to talk about her experiences, her family is too afraid to give her name to the media.

Without access to the girls themselves, we can only imagine what truly happened to them.

The Lost Girls

These young girls — long forgotten by all but their families — were allegedly kidnapped from their homes and forced to convert to Islam.

In December 2009, 13-year-old Radha Ram’s parents reported that she was kidnapped from their home in Rahim Yar Khan. She was kept in a madrassa and Abdul Jabbar, the leader of the madrassa, prevented the Hindu family members from meeting her since she was now Muslim.

Four men kidnapped 13-year-old Mashu from Jhaluree, a village near Mirpur Khas, on December 22, 2005. They then allegedly forced her to convert to Islam and renamed her Mariam. Pir Ayub Jan Sarhandi was involved in her conversion and soon after her abduction and conversion, she was married to one of the kidnappers.

Anita Kumar, a 22-year-old Hindu woman with two young children, was kidnapped from her house in Moro, Sindh in April 2011. In the process her two children, aged four and two, were beaten up and locked up alone in the house. The Supreme Court allowed her marriage to a Muslim man, even though she was still married to her first husband, Suresh Kumar. She has since then been renamed Aneela Fatima Pervez.

Gajri, a 15-year-old Hindu girl, was kidnapped by a neighbour from her home in Katchi Mandi in the Rahim Yar Khan district on December 21, 2009. She was later discovered in a madrassa, but by then she had already been converted to Islam and married to her neighbour, Mohammed Salim. Her parents later received an affidavit, in which the daughter stated that she had converted to Islam willingly but they were not sent a copy of the marriage certificate. The parents are not allowed to visit their daughter since they are non-Muslims.

On October 18, 2005, a Hindu driver, Sanno Amra, came home from work to find that his three daughters Reena, Usha and Rima had disappeared from their house in Punjab Colony, Karachi. The oldest sister was 21 and the youngest was 17 — legally still a minor. When Amra pursued the case he started receiving death threats and eventually found affidavits in the mail, which stated that his daughters had willingly converted to Islam. The parents were only allowed to briefly visit the daughters, and that too in the presence of maulvis and police officers.

This article was originally published in the April 2012 issue of Newsline under the headline “Unholy Vows.”

Zehra Nabi is a graduate student in The Writing Seminars at the Johns Hopkins University. She previously worked at Newsline and The Express Tribune.