A Military State

By Zahid Hussain | News & Politics | Published 21 years ago

The suspense over Musharraf’s uniform issue is finally over with the appointment of General Ahsan Hayat as the new Vice-Chief of Army Staff. It is now clear that the President is not quitting the military. This came as no surprise to most Pakistanis who had little faith in Musharraf’s commitment to the nation in December. The military ruler had already made his intentions clear last month when he declared in a TV interview, that 96 per cent of Pakistanis wanted him to stay on in uniform. The move has exposed Musharraf’s growing disillusionment with democracy and his penchant for personalised rule. It only confirms the people’s worst fear: the perpetuation of the military’s primacy over civilian power.

Musharraf’s newly installed Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz and the ruling coalition, who have shamefully surrendered the sovereignty of an elected parliament, negating all principles of political democracy, have blatantly aided and abetted Musharraf. They argue that it was necessary for the President to continue with his dual responsibilities in view of the war on terrorism and religious extremism. “We are in the midst of a war and important decisions on vital national issues are to be taken in the next few months,” says information minister, Sheikh Rashid Ahmed.

Predictably, Musharraf’s wavering has divided the nation and raised grave questions over the future of Pakistan’s nascent democratic process. The row over the uniform has intensified the political polarisation between the pro and anti-Musharraf forces. While both the Punjab and Sindh assemblies have endorsed Musharraf’s decision, the Frontier has voted against it, while the Balochistan assembly has remained non-committal.

The General defended his decision saying that he was a marked man and that the situation had changed since he made his promise last year. He said in an interview to a US publication, that the “renaissance” he was leading in Pakistan, would be in serious jeopardy if he shed his uniform. It is very obvious that his backtracking stems from a fear of losing hold. “Political leaders would start lining up to the new army chief once I announce my stepping down from the post,” General Musharraf was reported to have told his supporters.

Musharraf’s reneging has generated a constitutional row. Many constitutional experts contend that he is bound by the constitution to hold only one post after the end of the year and any change in the rule would require a constitutional amendment. The ruling coalition, however, deny that the constitution has been violated. The MMA, which had bailed Musharraf out on the LFO issue and supported the 17th amendment in return for Musharraf’s agreement to the December 30 deadline for taking off his uniform, has suffered a tremendous loss of face. The alliance has threatened to launch a nation-wide agitation to force Musharraf to step down. But there is little chance of it succeeding. The opposition is too divided to pose any serious challenge to the military ruler. The ARD has refused to join hands with the MMA only on the uniform issue, accusing the alliance of betraying the struggle in the past. This division has made Musharraf’s task much easier.

Though the fractious opposition is hardly capable of mobilising the people against Musharraf, political observers feel his decision to stay on in uniform will not go down well in the long term. By taking an extra-legal course Musharraf has blocked any chance of a peaceful exit. His legitimacy in office has become much more questionable, while Musharraf is now totally reliant on military support. His officers have so far stood firmly behind him, but growing public sentiment against his arbitrary rule is likely to eventually affect even the military’s ranks.

Musharraf has carried out his most major change yet in the army’s top brass since he seized power in October 1999. Following the appointment of General Ahsan Saleem Hayat as Vice-Chief of Army Staff and General Ehsanul Haq as Chairman Joint Staff Committee, six other senior generals have also retired. The retiring generals had fully backed Musharraf on his major domestic and foreign policy issues and the new appointments will also certainly be required to show total loyalty to their chief. The new appointments will be critical for Musharraf as he walks a very tight political rope. With the formation of the all-powerful National Security Council, Musharraf has enshrined in the constitution a permanent political role for the military and it is crucial for him to have those officers by his side who will fully subscribe to his views and policies. “Musharraf has ensured that he and military will continue to call the shots and maintain firm control on the levers of power. “Musharraf’s strategy is to maintain a façade of democracy and to retain control for himself and for the army,” says a former army general.

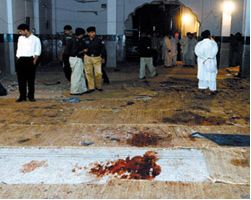

Musharraf is treading on political quicksand as the uniform issue comes to a head. The political system that he crafted so carefully appears to be floundering. Even the election of Shaukat Aziz, his handpicked Prime Minister, has failed to bring any political stability. Despite the government’s claim of combating extremism, the law and order situation is getting worse. The latest suicide attack on a Shia mosque in Sialkot that killed more than 30 people is a grim reminder that the religious terrorist networks are still intact and operating with impunity.

Musharraf is treading on political quicksand as the uniform issue comes to a head. The political system that he crafted so carefully appears to be floundering. Even the election of Shaukat Aziz, his handpicked Prime Minister, has failed to bring any political stability. Despite the government’s claim of combating extremism, the law and order situation is getting worse. The latest suicide attack on a Shia mosque in Sialkot that killed more than 30 people is a grim reminder that the religious terrorist networks are still intact and operating with impunity.

The grisly sectarian attack came just days after the killing of Amjad Farooqui in a shoot-out with police in Nawabshah. The killing of one of Pakistan’s most wanted terrorists, who was seen as an important cog in the Al-Qaeda network, was hailed by Musharraf as a serious blow to terrorism. But the situation on the ground is far from satisfactory. Fierce battles in South Waziristan against the suspected militants and their tribal supporters indicate that the situation is far graver than what the government has been portraying. More than 300 soldiers have been killed since the operation was launched in the treacherous mountainous terrain in March this year.

The unrest in Balochistan over development projects and the establishment of a new cantonment has also raised the spectre of renewed guerrilla war by disgruntled tribes. The situation is rapidly deteriorating because of the military government’s attempts to force a military, rather than a political approach to diffuse the problem. Musharraf’s decision to continue in uniform may stoke the fire further, rather than contain the problem.

The President’s decision to carry on as Chief of Army Staff is not likely to effect his relations with the United States which sees the military leader as a staunch ally in the war on terror, though US officials have been cautious on the issue. Some analysts believe Musharraf has won full backing from Bush during his recent meeting with him in New York. The uniform issue, however, will certainly create problems with Britain and the Commonwealth which had restored Pakistan’s membership conditionally earlier this year.

Musharraf’s wavering from his pledge to shed his uniform raises a host of troublesome issues. It is quite apparent that the continuation in power of a military president will entrench the military even more deeply in domestic politics and weaken the civilian institutions. Five years of Musharraf’s rule has enabled the military to spread out so widely in civilian institutions of state and society, that its presence is now firmly established in all walks of life. “The military under General Musharraf has undergone a major transformation, particularly in the outlook of the top commanders. They are no longer satisfied with the protection and advancement of their professional and corporate interests from the sidelines,” says Hasan Askari Rizvi, a leading defence and security analyst. The presence of the military is invasive. It has extended its role in the public and private sectors, industry, business, agriculture, education and communication.

Musharraf’s wavering from his pledge to shed his uniform raises a host of troublesome issues. It is quite apparent that the continuation in power of a military president will entrench the military even more deeply in domestic politics and weaken the civilian institutions. Five years of Musharraf’s rule has enabled the military to spread out so widely in civilian institutions of state and society, that its presence is now firmly established in all walks of life. “The military under General Musharraf has undergone a major transformation, particularly in the outlook of the top commanders. They are no longer satisfied with the protection and advancement of their professional and corporate interests from the sidelines,” says Hasan Askari Rizvi, a leading defence and security analyst. The presence of the military is invasive. It has extended its role in the public and private sectors, industry, business, agriculture, education and communication.

Like other states where the military has experienced long periods of military rule, in Pakistan too the military has become the ladder for lucrative jobs. Since coming to power, the Musharraf government has placed some 1200 active and retired officers in various ministries and state corporations. Retired generals are now serving as vice chancellors of the Punjab and Peshawar universities. The situation has not changed after the installation of a civilian government, and the private sector is encouraged to accommodate army personnel.

Most analysts agree that assigning military personnel into lucrative civilian jobs, coupled with the distribution of the rewards of power, has far reaching political consequences and carries a long term impact on the military’s professionalism. “The military has expanded its non-professional interest to such an extent that it has developed stakes in most areas of policy making and management,” says Rizvi.

Military rule has also helped consolidate the socio-economic conditions of officers through the perks that come with power. The military controls five foundations that are among Pakistan’s largest business groups. They run banks, insurance companies and major industries such as fertiliser and cement. They even own agricultural farms, dairies and gas stations. The military’s burgeoning industrial and business empire is indicative of its growing stake in the economy.

Several military welfare organisations like, Fauji Foundation, the Army Welfare Trust and Shaheen and Bahria Foundations, have become large industrial and business conglomerates. They are involved in varied business and commercial activities that include banking, running universities and schools in the private sector, real estate development and trading. Fauji Foundation, the largest, is now trying to acquire Pakistan State Oil ( PSO) and Ufone. The privatisation of PSO, that controls more than 70 per cent of the oil distribution business in the country, has been delayed to allow the organisation to search for a partner. The acquisition of these two companies with assets of more than one billion dollars may turn Fauji Foundation into Pakistan’s biggest industrial conglomerate.

The military’s land grabbing for the establishment of Defence Societies in Pakistan’s main cities has been scandalous. In Lahore alone the military has acquired more than 100 miles of land , extending from the new phase six, starting from Burki road to the BRB canal and across. According to a leading Pakistani economist, the value of this land alone is estimated at billions of dollars. This figure is multiplied manifold if land controlled by the military in other cities like Karachi is included. According to one estimate, around 35 per cent of Karachi’s prime land comes under the cantonment board. The military says they acquire the land at market prices, but the evidence contradicts the claim. ” It is a institutionalised corruption,” says Lt General (retd) Talat Masood.

Musharraf’s decision to hold on to his post and perpetuate the military’s primacy is bound to strengthen the military’s growing economic interests. With the political and economic stakes so high, the military is unlikely to relinquish their privileged position even after the restoration of civilian and constitutional rule. The more the military entrenches itself in non-professional fields, the less freedom political governments will be allowed in formulating domestic and foreign policies.

The writer is a senior journalist and author. He has been associated to the Newsline as senior editor at.