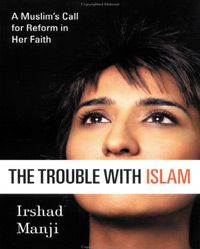

The Trouble With Manji

By Mahir Ali | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 21 years ago

Last month, Irshad Manji contributed an op-ed piece to The New York Times in which she suggested, in effect, that the occupation authorities shouldn’t be relying exclusively on firepower to subdue Iraq. It would do everyone a world of good if they could be equally generous on the micro-finance front. More specifically, they should establish means of offering small loans to women in order to encourage them to start their own businesses.

Last month, Irshad Manji contributed an op-ed piece to The New York Times in which she suggested, in effect, that the occupation authorities shouldn’t be relying exclusively on firepower to subdue Iraq. It would do everyone a world of good if they could be equally generous on the micro-finance front. More specifically, they should establish means of offering small loans to women in order to encourage them to start their own businesses.

This isn’t, of course, a novel idea. Although there is no mention of Bangladesh in the NYT article, in The Trouble With Islam, Manji cites the example of Mohammed Yunus and his Grameen Bank.

As a means of empowering women in societies where they generally lack the wherewithal to establish financial independence and the dignity that goes with it, it is an inspiring strategy. But proposing petty entrepreneurship as a broader panacea for the Muslim world, as Manji does at length in her often provocative (and that’s not a criticism!) book, requires not only chutzpah, but a liberal (or perhaps neo-liberal) dose of naivete. And in the case of Iraq, it is difficult indeed to envisage Grameen-isation getting very far amid the mayhem unleashed by the invasion and the response it has provoked.

All the same, were that the extent of Manji’s naivete, it would be easy to overlook. Unfortunately, it also manifests itself in far less agreeable forms.

But more about that later. First let’s look at what drove her to question the received wisdom about Islam. Transplanted as a child to Canada by parents evicted from Idi Amin’s Uganda, and in due course, compelled to attend a local madrassah, it didn’t take Manji long to discover that it wasn’t just another version of Sunday school. She was irked by the inability of the imam to answer her questions, which kept piling up as she grew older. What irritated her even more was the designation of many of her queries as inappropriate.

Eventually, the madrassah didn’t want her there anymore. She nonetheless resisted the temptation to make a clean break with religion. But the questions didn’t stop either. As a lesbian, she wanted to know why homosexuality is considered unacceptable in Islam. As a feminist, she couldn’t come to terms with the discrimination against women and girls. And she was equally concerned about the anti-Semitism that appeared to afflict most Muslims: what was the cause of it?

These, of course, are only some of the bones of contention. For obvious reasons, the hottest topic these days is terrorism. Not all Muslims are terrorists, Manji concedes, but aren’t all terrorists Muslims? That’s not an unfamiliar stance. It is based on the insidious view that if Iraqi insurgents blow up a military recruitment centre set up by foreign occupiers, that is terrorism; however, if US forces blow a wedding party or a family of civilians to kingdom come, that’s collateral damage.

Similar standards apply in the Israeli-Palestinian context, and it is quite amazing how Manji navigates the Middle Eastern maze almost exclusively from an Israeli vantage point. Invited to visit that country by what she describes as a Zionist organisation, she embraces with alarming fervour the right-wing Israeli dream. She can see little wrong with the occupation and is a bit too eager to defend Israel against charges that some of its policies are reminiscent of Nazism or apartheid.

Her views on Middle Eastern history and politics are based on the Zionist perspective. She would, if she could, remake the region in the image of Israel. She is filled with contempt for Yasser Arafat and full of praise for Israeli democracy, notwithstanding the fact that Ariel Sharon probably has more blood on his hands than any Arab despot.

Manji’s passion for all things Israeli — and, by extension, neoconservative — is an unfortunate and, on the face of it, unnecessary deviation from the intriguing challenges she posits for Islam, and it detracts considerably from the value of her witty and far from unintelligent diatribe.

However, it doesn’t follow from her jaundiced political perspective (although she persistently hedges her bets, possibly hoping thereby to fend off accusations of bias) that the other points she raises ought to be dismissed out of hand. After all, God knows that the malaise-ridden Muslim world needs to change. And Islam is crying out for a reformation.

It’s hard to disagree with Manji when she says that the way ahead lies via ijtihad rather than jihad. In her opinion, the trouble with Islam is that it has been hijacked by ‘foundamentalists’ — those who claim a monopoly over ‘true’ interpretations of the scriptures and traditions on the basis that they are native to the region where Islam was founded.

Muslims need to cast off this straitjacket, become more relaxed about their faith, accept and respect differences among themselves as well as with others, and realise that ultimately, Allah alone knows what is true and what is not. Ambiguities and contradictions in the Quran, she suggests, indicate that it ought not to be taken too literally.

Some of Manji’s arguments are more valid than others and most of them can, at the very least, serve as a basis for civilised debate. She has even provided a forum for such a discourse on her website: www.muslim-refusenik.com/home.html

Although she is clearly seduced by the West — and understandably enthusiastic about the freedoms she perceives therein — it is somewhat strange that she refuses to recommend what must surely be one of its finer attractions from the point of view of many Muslims: the separation, at least in theory, of church and state. And she errs equally grievously in holding out the hope that the push for change in Islam will come from Muslims settled in the West.

For a variety of reasons, it won’t. But even if it did, its chances of success would be slight. The impetus for movement towards a less rigid, more eclectic faith, must arise within the Muslim world. Perhaps it will. But don’t expect it to happen for as long as Manji’s ideological allies in Washington continue to pursue their disastrous ‘war against terror.’

Mahir Ali is an Australia-based journalist. He writes regularly for several Pakistani publications, including Newsline.