The Morning After

By Massoud Ansari | News & Politics | Published 19 years ago

In the picturesque village of Lamniyan, 63-year-old Hasina Begum sits listlessly near a pile of rubble, waving her hands to shoo away the flies swarming around her.

What used to be her home is now a place that haunts her. This is where she lost her husband, an 18-year old son,16-year-old daughter and two grandchildren when the massive October 8 earthquake struck her village, located over 6,000 ft up in the remote Jhelum valley.

“I do not have any strength left. When you reach my age, it is time to prepare for the life hereafter, but I have to start again from scratch,” says Hasina, who is now penniless.

The quake devastated an area of more than 30,000 square kilometers, killed more than 80,000 people and left about 2.5 million homeless in Kashmir and northern Pakistan. But Hasina survived along with her son and three grandchildren who were out in the forest to collect firewood at the time that the devastating quake struck.

Almost all the houses in the village of Lamniyan were destroyed and most villagers fled for safety to the makeshift camps set up by the government. They buried over a thousand of their fellow villagers, who died in the October earthquake. “Almost every house had two or three dead and there was no one to console them,” Hasina recalls.

Hasina and some her siblings were evacuated to the Chattar Class camp near Kohala district where they were provided food and medical care. A school was also set up for the surviving children. Five months after the quake, however, the government asked them to leave, setting March 31 as a deadline.

Many families tried to resist the move, but the government announced that those who chose to stay back would no longer have any benefits. Soon after the deadline elapsed, the NGOs supplying food rations and running schools as well as medical facilities in the camps were asked to leave. The government has since cut off water and electricity supplies in the majority of these makeshift camps.

Hasina’s son, Mohammed Yamin, said government officials had promised the affected that they would get transport back to the village, food rations for two months and 175,000 rupees for the reconstruction of their houses. “Once we packed our belongings and uprooted our tents, they gave us neither the money nor the transport to return. We have been here for three weeks now and there is no sign that we will get any kind of compensation,” he said.

Hasina’s son, Mohammed Yamin, said government officials had promised the affected that they would get transport back to the village, food rations for two months and 175,000 rupees for the reconstruction of their houses. “Once we packed our belongings and uprooted our tents, they gave us neither the money nor the transport to return. We have been here for three weeks now and there is no sign that we will get any kind of compensation,” he said.

Yamin said they are surviving on the money he was able to earn while he worked in Muzaffarabad, but he had no idea what would happen to the family once they consumed these savings.

Almost all the villagers in Lamniyan have returned to their villages and have more or less similar stories to tell. Most of them were allowed to take the tents from the camps and they now live in these tents in the villages, surrounded by piles of rubble.

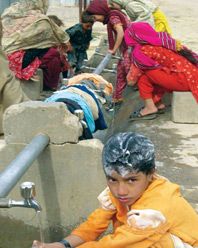

Young children in bare feet and tattered clothes can be seen wandering aimlessly in the valley. Many have not yet returned to their schools which had resumed functioning in temporary classrooms put up by NGOs working in these areas.

More than 2,400 of the 2,570 schools across the region collapsed during the earthquake, killing thousands of children. “There used to be 110 children studying in this school, but only 23 of them show up now,” says Abdul Rahman, a local teacher. He said many of the children perished, others were badly wounded.

The earthquake, which scored 7.8 on the Richter scale, was followed by almost 1800 aftershocks and these tremors continue to cause landslides which may worsen when the monsoon arrives in June and July. “The children get petrified every time there is an aftershock or when it thunders,” says Alafuddin, another villager.

There were also fears of over 10,000 children at risk of dying due to exposure and cold as 250,000 people above the snow line faced a life-threatening situation in the winter months. However, they were spared the worst as the winter was less severe this year.

The government as well as some aid agencies claim that the repatriation had to be undertaken on an urgent basis to prevent the villagers from becoming dependent on handouts. “The camp environment was causing multiple social problems and some camps had even become dens of prostitution,” argues Sardar Hussain Shah, secretary of the Pakistan Red Crescent Society, Muzaffarabad.

He said some people had become so dependent on free meals that they were not willing to work anymore. “It has become difficult to hire a labourer these days. Many of these people say that when they can collect free rations, then why should they work,” he adds.

He said some people had become so dependent on free meals that they were not willing to work anymore. “It has become difficult to hire a labourer these days. Many of these people say that when they can collect free rations, then why should they work,” he adds.

Some NGO activists, however, do not agree. Michelle Hawkins, Communications Officer, Médecins du Monde UK, says that given that current weather conditions are causing a number of landslides, and the conditions for a decent life in their village of origin will not be realised, it is reasonably difficult to envisage people returning. “The displaced people are still living in tents and a good number no longer have land or the financial means to rebuild their house and resume a normal life,” he said. It is a fact that thousands of villagers are constrained to stay on in the camps even after supplies have been cut off, as the roads leading to their villages are still blocked by landslides.

For example, roads leading from Chinari to Chikoti and onward to the Neelum valley were closed for several weeks due to a landslide. Similarly, villagers of the Kaghan and Naran valleys are still not in a position to return to their respective areas because roads in these areas have been completely wiped out.

Up to 150 refugee camps have already been officially shut down and those who choose not to leave the camps are being told that their compensation will be withdrawn.

But Abid Hussain, who lives in a camp near Islamabad, which houses nearly 6000 families, said living in a camp now is as good as being in jail. “They have withdrawn all the facilities, including food, and four of my children are sick,” he said.

Hussain said when he asked for transportation money, he was told that the camp inhabitants were ungrateful people and the authorities did not care how they returned,” he said.

Rasheeda Begum, a widow who lives in the camp along with her four children, says the family has been harassed by government officials. “They closed down the camp schools, stopped supplying us food rations, and are now threatening to cut off the water supply,” she said.

She said when the earthquake struck, it was the authorities who insisted that people should move to the camps. Every one was treated well and the Prime Minister himself came to inaugurate the camp school. “We never planned to be here forever, but we are surprised that the situation could change so drastically within the span of a few months,” she remarked.

She said that while some government officials had built palaces for themselves out of the money collected in the name of the earthquake, they were not parting with the basic funds needed to rebuild. “We told them from the very first day that we did not need supplies, we just wanted help to reconstruct our houses, but they were more concerned with photo opportunities to show the world that they were treating the quake victims well,” she said

Some of the villagers believe that the government wants to evacuate the camps because there are going to be elections in Kashmir after June and they want the number of voters to increase.

The government had announced the provision of 175,000 rupees for each house destroyed. However, just a few victims have been able to collect the first instalment of 25,000 rupees.

A local organisation has called for a general strike in the quake-stricken areas to protest the failure of ERRA (the Earthquake Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Authority), a body set up by the government to supervise the reconstruction activities, to provide compensation to these victims.

People complain that the ERRA authorities ask them to bring in the original ownership documents of their houses, to collect the first instalment of 25,000 rupees. “Many of the villagers have lost their documents after their houses collapsed, while some children are yet to get properties transferred in their name after their parents died in the earthquake,” says Khalid Mahmood.

Mahmood said the authorities had been asked to ascertain the legal rights of these families through elders and local officials in each village, but they had refused to accept this proposal. As a result, most victims have yet to benefit from the reconstruction fund announced by the government.