State of Discontent

By Siddhath Varadarajan | News & Politics | Published 23 years ago

As Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir heads towards elections that could prove a turning point in the region’s troubled history, it is clear that the government of Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee lacks a coherent and realistic strategy to deal with the problem. So convinced is the government that cross-border terrorism is the only issue to be solved that its entire focus is on using coercive diplomacy to get Pakistan to stop sending militants across the Line of Control (LoC).

As Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir heads towards elections that could prove a turning point in the region’s troubled history, it is clear that the government of Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee lacks a coherent and realistic strategy to deal with the problem. So convinced is the government that cross-border terrorism is the only issue to be solved that its entire focus is on using coercive diplomacy to get Pakistan to stop sending militants across the Line of Control (LoC).

In the corridors of power in New Delhi, hardly any importance is being attached to broad-minded internal political initiatives aimed at tackling the alienation of the average Kashmiri from the ‘national mainstream.’ When someone asked Vajpayee at a press conference in Srinagar in May what he intended to do about the fact that Kashmiris were “disconnected” from India, he angrily denied that any such disconnect exists.

How wrong he was. Even at the mundane, semantic level, Vajpayee should have known better. In end-December, he had presided over a Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) meeting which took the decision to cut all long-distance dialling facilities from public call offices (PCOs) in Jammu and Kashmir. Internet services were also suspended throughout the state, again in the name of “national security.” Apart from the huge financial losses the thousands of PCO operators and cybercafe owners had to suffer, the ordinary Kashmiri with no telephone or long-distance dialling facility of his own was left with no means of staying in touch with relatives in other parts of the country or world. Though the Indian government gave no formal explanation for putting Kashmiris into the communications equivalent of solitary confinement, telecoms minister Pramod Mahajan hinted that this was a temporary measure given the sensitive troop deployments underway in the aftermath of the December 13 terrorist attack on Parliament. However, no official could explain why PCOs in other border states — Punjab, Rajasthan and Gujarat — where troop deployments had also taken place, were not shut down. Clearly the message the government was giving the people of Jammu and Kashmir was that even though legally we consider you an integral part of India, we do not trust you enough to allow you access to telephones and the Internet, and that we reserve the right to connect or disconnect you any time we please.

The irony is that at a time when tension with Pakistan was at its highest and the Prime Minister was telling Indian soldiers in Kupwara near the LoC to get ready for a “final victory,” the CCS decided — in May — to restore public long-distance and Internet facilities in the state. Just like that. With no explanation or apology whatsoever.

The telephone incident provides a small illustration of the paradox that is so central to the way in which India deals with Kashmir. We swear it is an integral part of India, but turn a blind eye to government decisions which would provoke a major protest were they to be imposed elsewhere in the country.

Vajpayee’s Srinagar press conference was notable in another regard as well: he used the occasion to, once again, stress his commitment to free and fair elections in the state. The six-year life of the Jammu and Kashmir assembly expires on October 9 and, under the provisions of the state’s constitution, elections must be held before that date. Within the valley — and indeed the whole state — there is widespread apprehension that the polling process will not be free and fair. Apart from the fear of rigging by the state’s ruling National Conference of Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah, ordinary Kashmiris fear both the vote boycott fatwa of militant groups and the pressure that will be put on them by the Indian security forces to exercise their franchise. However, during my most recent visit to the valley I noticed a perceptible change in the rejectionist stance of the ordinary Kashmiri. Though he still doesn’t have faith in the integrity of the election process, he seems more suspicious of Abdullah than of the federal government. And in the event that the latter were to take some steps to insulate the elections from the interference of the former, it is quite likely that voter turnout — and enthusiasm for the polls — would be much greater than it has ever been since the Kashmir insurgency began in 1988.

Conducting state elections under governor’s rule — direct rule from New Delhi — is widely seen as the preferred option both among ordinary Kashmiris and senior officials in the centre. But legally and constitutionally, that would be a tricky affair if Farooq Abdullah decides not to cooperate since it would not be an easy matter for the centre to terminate the life of the state’s assembly before its due date. In any event, overseeing the elections so as to guarantee their free and fair nature is only one part of the problem; a more pressing concern is to broaden the field of credible contestants so that the state can begin to experience genuinely competitive electoral politics. Indeed, one section of senior Indian officials dealing with Kashmir would like nothing better than to give a few separatist leaders the chance to run the state government for a while. “Whether they like it or not, their constituents will force them to concentrate more on providing jobs, electricity and even security than on talking about azadi,” said a senior official.

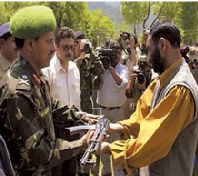

For the past six months, the Vajpayee government has been working on a loose strategy to entice some Kashmiri separatist leaders to contest the elections. However, the government has not invested the necessary political energies or capital to make this strategy a success. In particular, it has given no indication that it is prepared to show flexibility on some of the grievances of ordinary Kashmiris — the need for dialogue, the need to end human rights abuses by the security forces, the release of prisoners who have been in jail for years on end without the prospect of trials — so that those separatist leaders willing to enter the electoral fray would have something to show as an explanation for their volte-face. Among the three considered most likely to venture forward in some shape or form — either directly or by fielding proxies — were the late leader of the All-Parties Hurriyat Conference (APHC), Abdul Ghani Lone, the leader of the Jammu Kashmir Democratic Freedom Party, Shabbir Shah, and former commander of the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, Abdul Majid Dar. But the centre’s rigid stand left these three men vulnerable to charges of treachery and betrayal for being willing to “legitimise” the elections without getting any concessions for the Kashmiri people in return. The assassination of Lone by unidentified militants was rumoured to be a direct result of this process. Lone’s killing has also served as a warning to Shabbir Shah to stay well away from the elections. Shah now insists he will not contest but says that if the centre wants to make the elections credible, it must initiate a dialogue process with separatist leaders — including the APHC of which he is not a part. As for Majid Dar, he seems to have fallen victim to a turf battle between two Indian intelligence agencies, the Research & Analysis Wing (RAW) and the Intelligence Bureau (IB), with the latter leaking a news item through the official media that Dar has “expelled” Hizb commander-in-chief Syed Salahuddin. “That one planted news item has destroyed Majid Dar’s credibility,” a senior Kashmiri journalist told me in Srinagar in May. “Even if people suspected earlier that he was an Indian government agent, they will now be firmly convinced of this.”

Mirwaiz Maulvi Umar Farooq, another APHC leader regarded by New Delhi as a moderate, told The Times of India recently that there was no question of anyone in the Hurriyat contesting the elections unless the “purpose of the elections” was made clear. “If the election is aimed at choosing the true representatives of the Kashmiri people so that they can enter into negotiations with India and Pakistan for the resolution of the problem, then we will participate,” he said. “But if the idea is simply to legitimise the occupation of Kashmir by India, there is no question of anyone contesting.”

Mirwaiz Maulvi Umar Farooq, another APHC leader regarded by New Delhi as a moderate, told The Times of India recently that there was no question of anyone in the Hurriyat contesting the elections unless the “purpose of the elections” was made clear. “If the election is aimed at choosing the true representatives of the Kashmiri people so that they can enter into negotiations with India and Pakistan for the resolution of the problem, then we will participate,” he said. “But if the idea is simply to legitimise the occupation of Kashmir by India, there is no question of anyone contesting.”

Another dimension of the forthcoming elections that is receiving considerable attention is the question of neutral, non-official observers. The APHC proposal to set up a parallel election commission consisting of Indian, Pakistani and international personalities has been a non-starter, but a proposal by former Kashmir Chief Minister, G.M. Shah, and former Delhi High Court Chief Justice, Rajindar Sachar, for non-official Indian observers could well instil some confidence in ordinary Kashmiris. Shah and Sachar have asked the Election Commission of India (ECI) to grant observer status to a group of Indian NGOs and eminent personalities so that they can enter polling stations throughout Jammu and Kashmir to see the conduct of the elections. Though they would not be empowered to interfere with polling in the event of some irregularity, they would produce a report at the end in which they would pronounce their verdict on the degree to which the elections were indeed free and fair. With the Indian government reluctant to allow international observers, the Shah-Sachar proposal helps bridge the gap between the official election machinery of the Indian state and the Hurriyat plan for an independent election commission. However, so far the ECI has not reacted to this proposal with much enthusiasm.

As matters stand, therefore, the state appears to be heading towards a predictable outcome in the forthcoming elections — another six-year term for Farooq Abdullah’s National Conference. Abdullah would continue pretty much as he is doing now, or he may will draft his son, Omar Abdullah, to run the state and move on to greener pastures in New Delhi. However, the alienation and frustration of the ordinary Kashmiri will continue as his grievances continue to fester. Militant groups will find no shortage of local recruits to make good the shortfall due to heightened international concern about cross-LoC infiltration. In a few years, one could well be back to the days of the early 1990s when militancy was at its peak.

But is there something the centre could do differently in order to bring about a positive turn in the situation? There is, but only if Vajpayee is prepared to show the kind of political courage and flexibility he promised he would in his New Year musings from Kumarakom in January 2001. Then, the Prime Minister had promised to tread off the beaten track and repeated his claim that the key to any solution was insaniyat, or humanity. If he wishes to remain true to those words, there is plenty he can do.

The centre must realise that more than any economic package, the average Kashmiri wants respect and dignity. And the starting point has to be a clear acknowledgement by New Delhi of the tremendous wrongs it has done to the people of Kashmir over the past five decades. Along with such an acknowledgement and apology — which Vajpayee should personally make during a visit to Srinagar — there must be a demonstrated willingness to alter existing policies and patterns of behaviour, especially as far as the security forces are concerned.

Even though the scale of human rights violations is much less today than what it was in the mid-1990s, India pointedly refuses to deliver justice in those cases that have come to light. For example, either through sloppy prosecutions or deliberate design, the Border Security Force (BSF) ensured that none of its soldiers accused of the 1993 massacre of civilians in Bijbehara was convicted of the crime. When the National Human Rights Commission asked to scrutinise the trial proceedings, the BSF and the Indian home ministry refused, citing the need for secrecy in the national interest. Or take a more recent case, that of the cold-blooded murder of five innocent civilians at Panchalthan near Anantnag in March 2000. The five were abducted and killed by soldiers from 7 Rashtriya Rifles — a part of the Indian army — and policemen from the Kashmir government’s dreaded Special Operations Group shortly after the massacre of Sikh villagers in Chittisinghpora during the visit to South Asia of US President Bill Clinton.

At the time, the army, SOG and even Home Minister Lal Krishan Advani triumphantly announced that the five were Lashkar-e-Taiba terrorists responsible for the Chittisinghpora carnage. However, local residents suspected the slain men were the same five people who had gone missing in the Anantnag area one day before the encounter allegedly took place.

When the bodies were exhumed (after massive protests in which police firing claimed the lives of even more innocent people), relatives recognised the five men as their own. But since the bodies were “burnt beyond recognition” in the official description, the state government insisted that DNA verification be carried out first. DNA samples from the five corpses and blood from their relatives were collected and sent to two reputed Indian forensic laboratories in Hyderabad and Kolkata. The results proved to be negative but the Hyderabad laboratory stated in its final report that the blood samples had clearly been tampered with because in one case, blood purporting to be of a woman relative was actually that of a male, while another ‘female’ sample consisted of the blood of two males. Kashmir chief minister Farooq Abdullah appointed a one-man enquiry commission headed by Justice Kuchai, a former judge of the Kashmir High Court to look into how the samples came to be tampered with. He was asked to submit his report in two months. When I spoke to the judge in Srinagar in May, on the eve of the deadline, he revealed that his commission had not been given financial sanction yet and no official records pertaining to the case had been handed over to him!

In any civilised country, the tampering of blood samples in a case relating to the cold-blooded killing of innocent civilians would have been treated as a serious criminal case involving charges of accessory to murder. Not so in India or Kashmir. Fresh DNA samples have been taken directly by the Hyderabad and Kolkata scientists themselves but such is the cynicism in Kashmir today that no one — not even those officials personally convinced that the army had indeed murdered five innocent people at Panchalthan — believes justice will ever be done and the guilty punished.

However, Panchalthan provides a unique opportunity for the Indian government to come good on all its promises, to make a break with the past by doing the right thing. If it were to move swiftly to convict those soldiers and officers responsible for this sickening crime and to actually ensure that the death penalty were imposed and carried out, this one act of transparent justice could go a long way towards restoring the faith of ordinary Kashmiris in India.

Alongside the drive for justice and a push to end human rights violations, the Vajpayee government should invite to New Delhi all those Kashmiri politicians and leaders unhappy with the state being a part of India for unconditional dialogue. Leaders and politicians from Azad Jammu Kashmir and the Northern Areas — which India considers to be an integral part of its territory — should also be invited for dialogue. Any Kashmiri politician wishing to travel to Pakistan for consultations with Pakistani leaders and militant commanders should be allowed to do so. Simultaneously, New Delhi should open a separate negotiating track with the Pakistani government. Were such a dialogue process to be initiated, New Delhi would find many more people in Kashmir willing to contest and vote in the assembly elections. Especially if administrative measures of the kind discussed above were put in place. There would still be the threat from militant outfits eager to disrupt the elections either because of their own fears or because of pressure from Pakistan. But terrorism could easily be dealt with in a situation where the Indian government starts taking steps to win the trust of the ordinary Kashmiri.

None of these initiatives will lead to the easy resolution of the Kashmir problem. There is far too much bitterness in the relationship between India and the Kashmiris, and between India and Pakistan to allow for quick-fix solutions. But if the Indian government were to show courage at the present time, it could help to push the Kashmir conflict away from the military field where no side — not India, not Pakistan, not the Kashmiris — can win. Kashmir is at heart a political question, a political dispute. And only politics can help find a solution.