Pitching for Change

By Khalid Hussain | Sports | Published 19 years ago

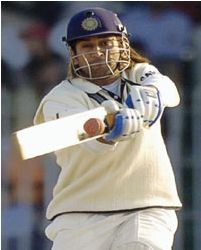

It was not a pleasant sight. Shoaib Akhtar running at full throttle and bowling a nasty beamer at the long-haired Mahindra Singh Dhoni as the Iqbal Stadium crowd cheered in the background.

It was the last ball of the 126th over of India’s first innings in the Faisalabad Test — inching towards a predictable draw — and Dhoni had previously hit the maverick pacer all over in that over. The ball came darting in at the in-form Dhoni and at 150 kph could have been fatal.

Shoaib offered no apologies, not even a fake one. He may have felt victimised himself, but Dhoni was not the villain of the piece. The man was only doing his job. It was the chappati-flat pitch or perhaps the people who made it or rather commissioned the making of it who should have faced the wrath of the Rawalpindi Express out there in the middle.

The incident was one of the low points of the worst kind of Test cricket can offer to its fans, sponsors, players and especially its bowlers. It wasn’t cricket, it was slaughter. And it came in the first two of what was anticipated as a mouth-watering three-Test series between two of the sport’s top teams with probably the hottest rivalry.

The two Tests produced 12 centuries as the batsmen from both sides had a field day and ran up some world records.

In Faisalabad, over 1700 runs were scored and just 28 wickets fell, most of them when the batsmen really didn’t care too much about their dismissal.

While batsmen like Younis Khan, Muhammad Yousuf, Virender Sehwag and Dhoni made the most of the run-fest, the bowlers — from both sides — had to go through a couple of weeks straight from hell. Shoaib and legspinner Danish Kaneria were touted as the trump cards for Pakistan while accomplished spinners Anil Kumble and Harbhajan Singh held the key for India before the start of the series. The four were among the big losers after the ordeals in Lahore and Faisalabad. Between them, the quartet had combined figures of 10 for 1181.

Cricket itself was, however, the biggest loser.

When the Lahore Test ended in a runs carnival, it was said that the real series would begin in Faisalabad. But another batsmen’s paradise at Faisalabad left everybody praying for a result at Karachi’s National Stadium in the final match. The three-Test series was reduced to something like a one-off Test.

So what went wrong with the multi-million dollar Allianz Test Cup?

Pakistan has a history of making batting-friendly wickets and not without reason. Though regarded among the world’s better teams, Pakistan has seldom had the services of reliable batting line-ups. So most of the time, while playing at home against strong opposition Pakistani captains play it safe and go for flat wickets. A draw is better than a defeat goes the logic behind such moves.

If it is left to the batsmen to decide the outcome of the series, then India, considering their current batting strength, would in any case beat Pakistan. If it were a timeless Test like the notorious 1939 Durban damp squib between England and South Africa, it is more likely that the score in Faisalabad would have gone India’s way. Just for the record, the so-called timeless Test ironically ended in a draw when England had to catch the boat home.

To decide a Test over five days on what was one of the most boring tracks ever laid for such a high-profile match was, however, next to impossible for any cricket side.

Why then would such a strong bowling side as Pakistan opt for tracks that showed total disrespect to their pacers? The cricket world blamed the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) and its chief curator Agha Zahid for the fiasco. The PCB and Zahid, on their part, blamed the cold weather in Punjab which they said hindered the preparation of sporting pitches.

Under pressure, the PCB even issued a press release to defend itself. The Board claimed it had prepared better tracks for the matches against England that preceded the visit by the Indians and had commissioned similar wickets for the series against India. Pakistan defeated England 2-0 in the series with one of the Tests ending in a draw.

But tell that to Pakistan’s outspoken former captain Rashid Latif and he would most probably be unable to conceal a smirk. “The difference is not between the pitches. It was the teams which were different. Pakistan had a better batting line-up than England and England had a better bowling attack than India. Pakistan and India are too evenly matched to be able to decide a match on such dead wickets,” says Rashid.

It has been an open secret that the problem in Pakistan, and at times in India, is that we in the sub-continent still don’t know the art of making proper cricket tracks. One can believe Pakistan skipper Inzamamul Haq when he claims that he wasn’t the one who ordered the nightmarish pitches in Lahore and Faisalabad. Probably nobody else did either. Agha Zahid may have tried his best to come up with good, sporting tracks, but the net result was the two awful pitches, producing a couple of Tests that were a sheer waste of time.

Stung by the harsh criticism, the PCB has vowed to take measures to assure better tracks in the future. In an effort to remedy the situation, the Board is now considering hosting an international workshop in which experts from various parts of the world will be invited for the exercise. The idea is to garner their help in a bid to improve the sub-soil so that the tracks made here are able to produce the required bounce to make the contest between the bat and ball less lopsided. The Board would also be seeking assistance from the Turf Institute of New Zealand and has asked them to send an expert to Pakistan soon after the series against India.

One option that seems feasible is drop-in pitches. These pitches are prepared in indoor laboratories and are already in use in some parts of the cricket world. Trans-Tasmanian rivals Australia and New Zealand have used them quite successfully, though for different reasons.

The 2005 Boxing Day Test between Australia and South Africa was played on such a track. It was an exciting match which was a great contest between the bat and ball. Aussie all-rounder Andrew Symonds produced match-winning performances, both as a batsman and bowler, to lead his side to a memorable triumph.

To facilitate similar matches in Pakistan, PCB will have to think and act fast. Cricket should remain a game of glorious uncertainties and should not be allowed to become a dull sport played on farcical tracks.

The writer is ranked among the battle-hardened journalists covering sports. As sports editor for The News, he covers sporting action extensively in Pakistan and abroad.