Miniature Exodus

By Salwat Ali | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 20 years ago

The contemporary miniature is no longer ours to have and to hold. The best, choicest pieces are now gracing gallery walls abroad, while viewers at home have to contend with seconds. The genre’s popularity level, especially in the UK and USA, continues to soar, endowing it with a ‘hot property’ status, while generous prices in foreign currency when translated into rupees render the art form well out of reach for the average Pakistani buyer.

Thematically as well, the new miniature has changed. Initially addressing domestic problems, frequent opportunities to exhibit abroad brought a distinct change in the artistic mindset. The focus has now shifted to geo-political concerns and social issues like gender discrimination, violence and terrorism with another viewership in mind as these are popular issues of debate in the west. Moreover, some talented miniature graduates have settled abroad and are emerging as diaspora artists. Living a bi-cultural existence, they are voicing their own dispersal and bringing new interpretations to old issues. This is shifting the miniature further away from home-ground towards a global centrality.

And then the genre has also begun to lose its inherent classicism as miniature artists succumb to varied artistic styles and techniques. Presently the potpourri is still delectable, but a feeling of alienation is beginning to set in as the medium homes in on bigger and more lucrative markets. When we see indigenous art establishing an identity abroad, there is an obvious sense of pride, but home audiences are being left behind. A stronger foothold at the source of origin will give longevity to the genre. Art should live in the hearts of the people not just in the pockets of the investors. If the miniature is bent on mounting the roller coaster, the fun might end after a few dizzy spells.

A two-artist exhibition held at Canvas recently centred on contemporary miniatures by Nusra Latif and personal statements in different media, by Navin Hyder. Nusra Latif currently lives and works in Melbourne. She acquired her BFA from the National College of Arts in 1995 and completed her MFA from the Victoria College of Art, University of Melbourne in 2002. As a miniature artist she has had solos at home and abroad since 1999, while her most recent exhibition was ‘Intentions of Memory’ in 2005, at the Mc Leeland Print Room, Melbourne. She has also been a participant in major group shows of the miniature outside Pakistan, the latest being the Karkhana show, ‘A Contemporary Collaboration,’ at the Aldrich Museum, USA.

A two-artist exhibition held at Canvas recently centred on contemporary miniatures by Nusra Latif and personal statements in different media, by Navin Hyder. Nusra Latif currently lives and works in Melbourne. She acquired her BFA from the National College of Arts in 1995 and completed her MFA from the Victoria College of Art, University of Melbourne in 2002. As a miniature artist she has had solos at home and abroad since 1999, while her most recent exhibition was ‘Intentions of Memory’ in 2005, at the Mc Leeland Print Room, Melbourne. She has also been a participant in major group shows of the miniature outside Pakistan, the latest being the Karkhana show, ‘A Contemporary Collaboration,’ at the Aldrich Museum, USA.

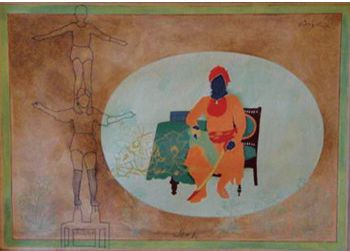

Nusra’s work at Canvas does not reveal itself immediately. The female figures, seated or standing, are executed in the traditional Mughal style and they have a defined presence, but with a quiet reserve about them. Their body language gains meaning when the artist discloses, “The work for this show is an exploration of a woman’s childbearing capacities, how her body changes, miscarriage, emotional changes and expectations.” Especially relevant in this regard is ‘Silent Spaces,’ 1and 2. Her vocabulary of organic imagery in the form of floral bursts, bouquets and foliated stems also supports her stance on life and growth. Integrating nature with human existence, she weaves a narrative on different aspects of life. Elaborating on her approach, she asserts “I try to maintain a point of view distinctly from a woman’s position, be it a reflection on political disorder, or personal relationships.”

Technically, Nusra’s miniature grounding loses none of its strength as she ventures into interactive stylisations. She negotiates the unbroken line with a very controlled hand, which is particularly evident in her very direct drawings of floral sprays. But she has been far more inventive in her previous works where figurative and floriated outlines intertwined to suggest larger meanings. The artist makes novel use of the decorative pattern, using it as a design ploy as well as a conceptual metaphor. The dagger image, a historical emblem, also signifies death and destruction. In ‘Silent Spaces 1,’ colour application is given a contemporary twist. Instead of the old miniatures’ jewel-like brilliance, the red and green contrast is bold and dramatic. However, other images are pale and mellow with a spare use of white and gold.

When questioned about the steep price tags that miniatures command nowadays, Nusra remarked that prices are escalating because Pakistanis are now becoming more aware of their own art and their spending power has strengthened the market. Regarding the miniature genre specifically, she says, “miniature paintings are not sold by the square inch. Painters have to fetch prices that are comparable to other artists. Some artists have been around for ten years, and there has been a gradual increase not an overnight one.”

When questioned about the steep price tags that miniatures command nowadays, Nusra remarked that prices are escalating because Pakistanis are now becoming more aware of their own art and their spending power has strengthened the market. Regarding the miniature genre specifically, she says, “miniature paintings are not sold by the square inch. Painters have to fetch prices that are comparable to other artists. Some artists have been around for ten years, and there has been a gradual increase not an overnight one.”

Printmaking is a less understood genre with a low popularity profile and the digital variety has yet to gain credibility as an authentic artwork. Art buyers wondering why Nusra was selling her miniature digital prints for as much as Rs 30,000, almost the price of a good original, may agree with her reply.

“Regarding the price of my digital prints, I must clarify that it is not the average dodgy, digital, bubble jet print. The technology has advanced considerably in the last few years. The specialist art printer I am using is very good and different from the normal office printer. It costs quite a lot and the prints have a long life.” Nusra’s digital prints in editions of thirty, are printed on archival paper with pigment inks and they have a life stretching over a hundred years.

The art of Navin Hyder, the other participant in the show, is a study of contrasts. She seems to be locating herself between the loud and the oversized and the subtle and the minimal. She is not pushing herself to arrive at any conclusions, preferring to explore her choices and remain open to diversity. Her series titled ‘Waiting,’ spread over six pairs of drawings, displays her ability to economise her strokes. Each frame has a lone figure sketched with the barest number of lines in an expectant or non-interactive posture. A graphic traffic symbol, signifying the appropriate ‘waiting’ symbol, accompanies each sketch. The artist has something going for herself here, the works are engaging and can be developed to advantage. Her large canvas pieces, partial close-ups of the human face, with primitive stroke-work, truck art stickers and cheeky humour seem brash in comparison.

Navin Hyder is an Indus Valley graduate from the batch of 2000. She spent an extra year to complete her thesisin miniature painting. With considerable teaching experience behind her, she is presently attached to the faculty of the Fine Arts department of IVSAA. As an artist she has participated in a number of selective group shows and her solo ‘Whaam’ was held at Rohtas 1and 2 sometime ago. A residency at Gasworks in London, this year is the most recent addition to her career profile.

No more posts to load