Defining Convictions

By Aquila Ismail | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 20 years ago

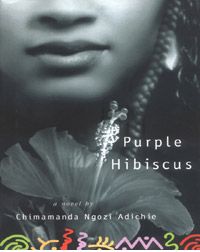

From the very first line of Purple Hibiscus, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s debut novel, “Things started to fall apart at home when…,” one knows that it has deep roots in Chinua Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart, and as one reads it one finds the many connecting threads. Both books revolve around a powerful man who, instead of fighting for what he perceives to be traditional ways, fights on the side of the most domineering of the white missionaries. However, while Achebe’s book is a man’s look at society, Adichie tells the tale through the eyes of a shy 14-year- old girl, Kambili.

From the very first line of Purple Hibiscus, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s debut novel, “Things started to fall apart at home when…,” one knows that it has deep roots in Chinua Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart, and as one reads it one finds the many connecting threads. Both books revolve around a powerful man who, instead of fighting for what he perceives to be traditional ways, fights on the side of the most domineering of the white missionaries. However, while Achebe’s book is a man’s look at society, Adichie tells the tale through the eyes of a shy 14-year- old girl, Kambili.

In Kambili’s family there are too many things that are never talked about, and Kambili and her brother, Jaja, thereby become metaphors for domestic violence and ‘Catholic’ repression. They are forced to be high achievers so that their father can point to them with pride as extensions of himself in the world.

The novel is set against the background of the military coup and subsequent political upheaval in Nigeria, which brought General Abacha to power. At the beginning of the story, we see Kambili sequestered behind the high walls of her family compound. Her wealthy Catholic father is generous and well-respected in the community, but is cruelly repressive and fanatically religious at home.

Kambili lives her life circumscribed by schedules, which give an inordinate amount of time to prayer. The father is excessively violent to the extent, as Kambili finds out later, of being the cause of several miscarriages suffered by her mother. So brainwashed is she that even the emotional and physical pains he inflicts are seen as a gesture of love for their own good. Later, however, she comes to consider his actions as abnormal.

When Nigeria begins to fall apart, the father, who owns factories and the country’s most outspoken newspaper, which continues to print the truth and ask difficult questions even after the military coup, is forced to go underground. So he sends Kambili and Jaja away to their Aunt Ifeoma. This house offers a complete contrast to Kambili’s: it is full of laughter. Ifeoma’s strong character, outspoken and independent views and her roaring laughter fill Kambili and Jaja’s life with charm, warmth and openness. Ifeoma fights against poverty and instability at the university campus where she lectures. This is where the children experience Nigerian everyday life for the first time — and another reality, where anyone is allowed to express their thoughts at the dinner table. Here Kambili discovers love and a life beyond the confines of her father’s authority. This visit lifts the silence from Kambili’s world and reveals the terrible, bruising secret at the heart of her family life.Kambili is more than the protagonist in the novel. In fact, she is telling a story that is bigger than she is and her role seems to be to observe. She speaks through the narration and this is something she rarely does in her life at the beginning.

Though the novel is written in English it is liberally peppered with Igbo, the local language that Kambili’s family speaks. The result is mixed. While it gives the narrative a richness at times, it slows down the narrative at others. Adiche perhaps wished to depict the reality of narration in her society where people speak English in formal settings and Igbo in informal ones.

Occasionally, Adiche falters with the copious detail about the land and the people. Also, the eating never stops. Nearly every page mentions some kind of food, from coconut rice, cashew juice, vendors selling bread in hot banana leaves, palm wine etc. Food is a very strong cultural expression. What you eat defines not only your ethnicity but also your class. However, all that mention of food renders the story a bit sluggish. But overall, the vivid picture of the people, the individual, the fruits and food and dust and the purple hibiscus add to the intense colour and richness of Nigerian life.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who grew up in Nigeria, was shortlisted for the 2002 Caine Prize for African Writing. Her work has been selected by the Commonwealth Broadcasting Association and the BBC Short Story Awards. Adichie is building her next novel around the Nigerian civil war of the late 1960s, which we know mostly from news photographs of starving Biafran children. Most of her research is oral, coaxing stories from village elders. Besides watching news shows and voicing her strong political opinions, Adichie has no passion other than writing. “Sometimes I wonder if it wasn’t for my writing, I don’t think I would be me,” she says. “It’s just such a part of me that there isn’t room in my life for anything else.