Anarkali Revisited

By Samina Ibrahim | Arts & Culture | Published 21 years ago

Notwithstanding the debate on the merits of the choice of the Anarkali legend recently staged in Los Angeles, New York and London, the fact is that just three shows raised close to a hefty 1.5 million dollars for the National Commission for Human Development. Funds that will be disbursed in Pakistan for the NCHD’s primary and adult literacy programs. And that is basically the bottom line.

Notwithstanding the debate on the merits of the choice of the Anarkali legend recently staged in Los Angeles, New York and London, the fact is that just three shows raised close to a hefty 1.5 million dollars for the National Commission for Human Development. Funds that will be disbursed in Pakistan for the NCHD’s primary and adult literacy programs. And that is basically the bottom line.

Anarkali was not conceived as a vehicle to promote Pakistan’s image abroad — it was purely a theatrical exercise in cultural aesthetics commissioned by the NCHD to raise funds. Which it did, and that too a substantial amount. The fact that the play was extremely well received in all three cities was a welcome bonus for all those involved in the project. Says Dr. Nasim Ashraf, Chairman NCHD, “Rizwan put together a first-class show and I consider him an asset for Pakistan.” Farrokh Captain, the executive producer for Anarkali and the Chairman of the Pakistan Human Development Fund, says the show and the response exceeded his expectations.

For Anarkali’s director, script-writer and costume and jewellery designer, Rizwan Beyg, the project was a personal challenge. “When I was first approached, I was not too keen,” says Rizwan.” I felt it was too hackneyed a theme. But as I researched and read up on the legend, I began to look at it differently. To me it functioned on different levels. It was about three women: Akbar’s queen, the powerful, but lonely Jodha Bai; the treacherous Dilaram who betrays the lovers in her quest for power, and Anarkali, the purest of them all, who “dies” for her love. Most significantly it was about one man — the all-powerful Emperor Akbar and his idea of justice. It was an interesting parallel to what’s happening in the world today — where just one man, George Bush, decides the fate of the world.”

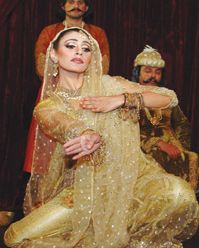

Rizwan presented the legend on stage using two traditional sub-continental genres: nautanki and kathak. “Nautanki is the age-old tradition of a travelling troubadour troupe who toured villages presenting plays mimed against a narrated backdrop,” says Rizwan. “And on a larger level, that is what we were doing: taking the show to three different cities. I also used kathak, which is basically dance-drama, and an art form which was purified and perfected at the Mughal court.”

Translating the concept into reality, however, was no easy task. First was the decision to the take the traditional versus the contemporary interpretation. Rizwan opted for the traditional simply because there are no modern-dance traditions or institutions to audition from. “The worst thing one could have done was to have taken raw students performing an unfamiliar style and present it as a professional show,” says Rizwan. “So finally we decided that a period piece would be the only thing that would enchant audiences abroad. As it turned out, it was a wise decision.” “Anarkali was a unique treat for guests who were both Pakistani in origin as well as the many who were not,” says Madhya Farooqui, who saw the New York show. “While modernity and tradition often meet beautifully, its a tough act to pull off and one has seen too many fouled attempts. Far better is a polished traditional performance than a struggling amateur “modern” interpretation.”

However, even finding Pakistani kathak performers of the calibre Rizwan was looking for, proved to be impossible, so he contacted New York-based Parul Shah, a student of the world famous Kumudini Lakhia. Parul and her troupe flew into Lahore for six weeks of rehearsals and she choreographed all the dance sequences. The rest of the cast was Pakistani with Nauman Ijaz playing Emperor Akbar, Masarrat Misbah Empress Jodha Bai and Irfan Nazir as Prince Salim. The narrator was none other than Zia Mohyeddin who apparently did a superb job of handling such an ambitious project. The musical score was based on the Thaat Asaveri, while the primary raag was the raag darbari written by Tan Sen and performed on the night Prince Salim was born. The soundtrack included 13 songs and was put together by Safia Beyg who runs the Sampurna Musical Academy in Karachi. The vocalists were Intezar Hussain, Ustaad Nazeer Saamee and Shabana. “It was quite a nightmare synchronising the dances with the music,” says Rizwan.

However, even finding Pakistani kathak performers of the calibre Rizwan was looking for, proved to be impossible, so he contacted New York-based Parul Shah, a student of the world famous Kumudini Lakhia. Parul and her troupe flew into Lahore for six weeks of rehearsals and she choreographed all the dance sequences. The rest of the cast was Pakistani with Nauman Ijaz playing Emperor Akbar, Masarrat Misbah Empress Jodha Bai and Irfan Nazir as Prince Salim. The narrator was none other than Zia Mohyeddin who apparently did a superb job of handling such an ambitious project. The musical score was based on the Thaat Asaveri, while the primary raag was the raag darbari written by Tan Sen and performed on the night Prince Salim was born. The soundtrack included 13 songs and was put together by Safia Beyg who runs the Sampurna Musical Academy in Karachi. The vocalists were Intezar Hussain, Ustaad Nazeer Saamee and Shabana. “It was quite a nightmare synchronising the dances with the music,” says Rizwan.

Apart from creating the costumes and the jewellery, Rizwan also wrote the script and together with Nauman, trained the actors and designed the sets. “I took my inspiration for the costumes and jewellery from Mughal miniatures and Ritu Kumar’s book on Indian costumes,” says Rizwan. “I had to go to Jaipur to make the jewellery because it was too expensive in Pakistan. The whole project took seven months, while the rehearsals, which were divided into dance and theatre, took three months.”

Anarkali opened in the States at Universal Studios in Los Angeles to a 700-strong audience. The performance has subsequently been entered in an event competition by the event managers in LA as their favourite show for 2004. New York was probably the highest attended, courtesy General Musharraf’s presence, though there were complaints that the show started far too late. The most polished performance, however, was seen by the London audience which included designers Bhatti and Joe Bloggs, who had flown in specially for the event. As Dr Maleeha Lodhi put it: “It was a spectacular show and Rizwan has really done Pakistan, proud. I was particularly delighted when Indian members in the audience specially came up and said that they had not seen a show like this, even in India.”

“Bhatti, in fact, wanted to take the show to Paris,” says Rizwan. “While in New York, I was approached by a Broadway director who suggested redesigning the show as a Broadway musical. We already have offers from five other cities in the States who want to sponsor the show, so I guess you could say Anarkali was not just a fund-raising success for NCHD, but also proved that Pakistan can put together a professional stage show with the elements of costume, dance, drama and music. For me, personally, the response in all three cities was very gratifying. And since I specifically designed it as a travelling show, Anarkali can be performed equally effectively in Tokyo or Paris with just a simple narration translation.”

And if he were to do Anarkali second time around, what would Rizwan do differently? The story line for starters. “When I was writing the script, I took artistic license with the legend and changed the ending: Anarkali was ostensibly walled up by Akbar, but was in reality spirited away and married off to the Persian Sher Afghan. Years later Jehangir saw and recognised her and married her in her new persona of Nur Jehan. Others involved in the show, however, felt I should not tamper with the legend so I dropped it,” says Rizwan. “But that is how I would have ideally liked to have portrayed it. Also I would change some of the actors and perhaps some of the sets.”

Perhaps Anarkali is the beginning of yet another aspect of Rizwan’s continuing creative journey.