The Lost Boys

In December 1999, an unassuming, middle-aged man walked into the Jang newspaper building in Lahore, claiming to be Pakistan’s most notorious serial killer. Javed Iqbal, who had the police on high-alert for over a month in what is known as the country’s biggest search operation, was immediately arrested and put behind bars.

His victims? Over a 100 street children, he claimed — poor and destitute, often runaways, who roamed the streets of Lahore and slept on its pavements.

During the trial that followed, Iqbal boasted that he could have gone on to kill hundreds more before any form of action was taken by the authorities. Nobody notices the disappearance of a street child, he said.

One man’s depravity was for all to see and condemn, but there was a larger issue that emerged from this case: society’s apathy towards the street child. These children were victims at the hands of a sadist and his accomplices (all teenage boys), but they were also victims of criminal negligence by both state and society.

Where the government fails its citizens, there are a few organisations that are taking on the responsibility of giving these children the possibility of a better future. Newsline spoke to Rana Asif Habib of the Initiator Human Development Foundation (IHDF) in Karachi and Shaista Naz from the DOST Foundation in Peshawar on the lives of street children, the work that is being done by their organisations and the work that still needs to be done.

IHDF was founded by Rana Asif Habib in response to the Javed Iqbal case in 1999, but it wasn’t until five years later, in 2004, that it became a non-profit institution, with an office in Saddar that has its doors open 24/7. IHDF has a home where children can come to rest, eat and get free medical care. It also serves as a rehabilitation centre for child drug addicts. They can stay for as long as they like, given that they respect the three rules of the home: no smoking, no drinking and no fighting.

If they wish to pursue an education, the organisation assists them in achieving their goal. All the support it receives is on a volunteer basis, with students, lawyers, psychologists and media persons extending a helping hand. In 2008, the institute started a helpline service with Telenor (the Meri Helpline Project), through which instances of child abuse can be reported. They also have street-motivators who approach children on the street, develop a rapport and make them aware of the help that is available.

DOST Foundation, too, gets word out about their organisation through their open-road policy and outreach team. Founded in 1992 in Peshawar, the organisation provides counselling, medical help, healthy recreational activities and temporary housing. If children wish to reconnect with their families, both organisations facilitate reunions as well. In addition, DOST Foundation speaks to the families to settle conflicts. However, because many of these children come from broken families, they often return back to the streets. Unfortunately, despite their best efforts to rehabilitate, the chances of relapse are high. According to Naz, when their outreach team meets a former resident, many report returning to drug abuse and other illegal activities. Out of all the children that come to their centre, only 20-25 % are success stories, adds Habib.

According to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the terminology accepted by the government and NGOs worldwide, anyone 18 and under is considered a ‘child.’ As such, an estimated 1.2 million children live and work on the streets in Pakistan’s urban centres. Karachi faces many of the same issues as other metropolises in the developing world, where grinding poverty resides beside sprawling shopping malls, and the number of street children is said to be around 30,000. However, many, including Habib, believe the actual figure to be much higher, especially taking into account that many children live with their families on the street, but are not officially counted as ‘street children.’ In Peshawar, the number is said to be 45,000, but once again, these are disputed figures.

The majority of Karachi’s street children are Bengali and Burmese (45%), Pakhtun and Afghan (25%) southern Punjabis (20%) and the remainder are Baloch (10%). In Peshawar, most children on the street are locals, or from other cities in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa such as Swat, Charsadda and Mardan. A small minority are from Afghanistan.

Children run away from home for a number of reasons, but poverty and domestic violence are the predominant ones. These children are made into “thekedaars” of their families and forced to earn at an early age, says Habib. More often than not, there is some form of mistreatment by their families, at their place of work or in their schools and madrassas.

Regarding the psychology of the street-child, Habib says: “You’ll notice something unusual about these kids, which is a result of their innocence, that you won’t find in other children: they have a peculiar wanderlust. They trust others easily, and if a stranger offers them a ride somewhere or the promise of adventure, they hop on the chance.” That innocence makes them more vulnerable to predators and mafias. They are picked up at truck stands and from places where they are offered free food. On the other hand, Naz believes that street children are generally untrusting of adults. “They are mature themselves; their experiences impel them to be. They can also be tez and manipulative, but they have to be for their own survival.”

Once on the street, their first interaction is with the police, with whom they establish a familiarity and sense of friendship. But this is not without strings attached, as the police take a fraction of their earnings, reveals Habib. They get involved in drugs such as heroin which is cheaply available and glue-sniffing. Once on drugs, crime isn’t far away, as they get involved in drug-trafficking, theft, pick-pocketing and other crimes.

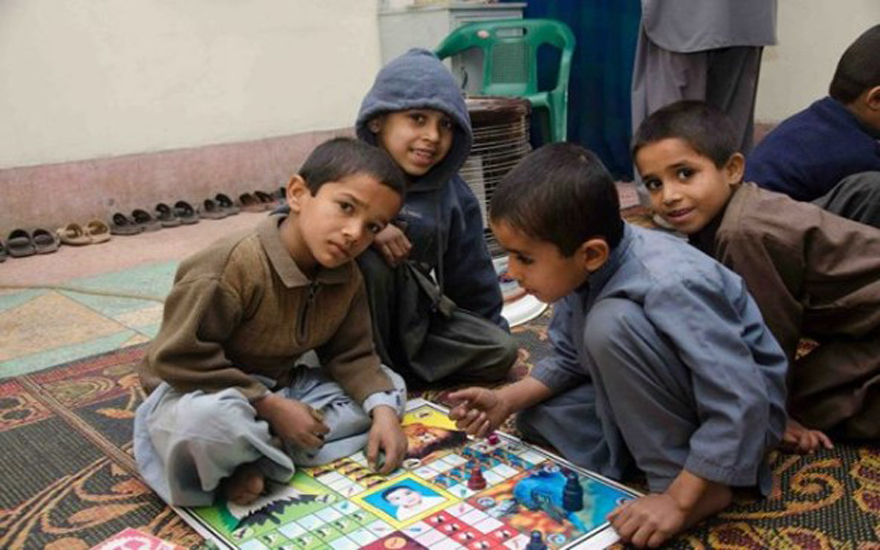

Dost Foundation offers temporary housing and healthy recreational activities for Peshawar’s street children.

Habib adds that there are many layers of street children, but divides them into two broad categories: “street-living” and “street-working.” Amongst the street-living, 90% are boys whereas within street-working, the gender demographics are equally divided, with 50% girls and 50% boys. As expected, it is the street-living who face the most problems and are the most vulnerable. At every level, there is abuse (both physical and sexual) and the threat of abuse. While street-working children, girls in particular, have a shelter and some form of family protection at night, Habib says that every one out of nine street-living boys in Karachi report sexual abuse of some form within the very first night of being out on the street. Naz adds that victims become perpetrators, as the older boys go on to sexually abuse younger children, thus creating a cycle of abuse. Many contract STIs, TB, skin, dental and kidney problems while on the street. There are even cases of HIV. Their environment and the frequent bomb blasts in Peshawar also have a negative impact on their psychology. “They look to hurt others or they resort to hurting themselves,” she says.

In a sea of predators, there is a new player: the militant. It’s no secret that the Taliban and other extremist outfits use children to carry out suicide bombings. In an article for The London Review of Books in 2012, Owen Bennett-Jones reported that a 15-year-old youth, who had run away from his home over a year ago, was behind the suicide attack that killed Benazir Bhutto in 2007.

Habib agrees that there is always the threat of street-children being coerced into militancy, adding that extremism is not restricted to any one ethnic group, but where there is a shared cultural understanding, there is more of a propensity to join the ranks of militants. However, Naz says that while it is a possibility, DOST Foundation has not come across such a case so far. “I can’t speak about militancy, but they do get involved in other antisocial activities, which they see as necessary for their survival,” she says.

Habib does not mince words when it comes to expressing his disappointment with both the government and the NGO sector: “If you criticise the government, they will completely ignore you and your organisation. But critical analysis is important for a healthy society. As for the NGOs, they operate from nine-to-five, but most cases of abuse do not occur in those hours. Many people have gotten rich by taking up the cause of children, but the children remain where they were. Their work is restricted to mainly seminars and conferences, and the changes are on a cosmetic level.”

The media has its fair share of detractors, but Habib is not one of them. His biggest supporters, he says, are people in the media — morning talk-shows, in particular, where he is a frequent guest.

So what work needs to be done?

“More rehabilitation centres need to be set up, so that children are never without shelter. There are so many empty government buildings in Karachi that can be put to use. Secondly, one must get involved in policy-making and look into institutional changes, as the biggest detriment is the charitable approach.

“In addition, the Child Protection Authority has still not been set up. Considering that 43% of the country’s population is under the age of 18, there is a need for the Child Protection and Welfare law to be passed and the establishment of a special ministry for children.”

On an individual level, one should approach these children with “love and affection,” says Habib. “People are often suspicious of them, based on their own negative experiences. I urge others to see them for what they are: minors that are being exploited. They are failed by all those who should have protected them — their families, neighbourhoods, educational institutions and, finally, by the state. We should not ignore them.”

“When I left, I didn’t know what I was getting myself into”

-Former Street Child, Tanveer Abbas

Tanveer Abbas was just 12 when he ran away from home. For the next seven years, he would roam the streets of Saddar along with friends he made along the way, sleeping outside Student Biryani and doing odd jobs to make ends meet.

Tanveer Abbas was just 12 when he ran away from home. For the next seven years, he would roam the streets of Saddar along with friends he made along the way, sleeping outside Student Biryani and doing odd jobs to make ends meet.

Born in Vehari, Tanveer’s family moved to Karachi when he was five. “We were just like any other poor family. Nothing special.”

But as with many ‘ordinary’ families, corporal punishment and violence at home was common. He recalls having stolen some money from his mother’s purse, and the fear of punishment (“My father had a terrible temper”) kept him from going back. He was also never particularly interested in school or getting an education. “When I left, I didn’t know what I was getting myself into. ‘Where am I going?’ ‘What am I looking for?’ I never asked myself these questions. I just left.”

“Begging, cleaning cars, scavenging, going to people’s homes to clean or help with heavy-lifting… I’ve done it all,” he says with a yawn. “I won’t say living on the streets was good exactly, but it wasn’t as bad as it is today. We didn’t have the kind of random violence that we do now. No one questioned us about where we were from or where we were going. Other than the police (we lived in the vicinity of two thanas), who would bother us because they wanted to clear the area, no one else really cared.”

However, while the police were a mere nuisance and the political party workers indifferent, there was a real threat: “We were aware of the mafia. We knew they exploited children and made them do bad things. A few of my friends got caught in their trap.”

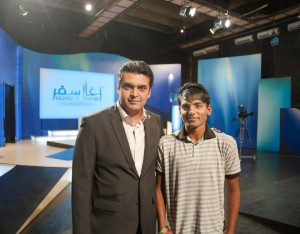

In May this year, Tanveer appeared on Aghaz-e-Safar (his fourth television appearance), hosted by Fakhr-e-Alam, and spoke about the issues he and other street children face. He recounted when he was gang-raped by adults he trusted, and the emotional trauma it caused him for years, as he would battle suicidal thoughts.

Was it difficult to speak about his ordeal in front of an audience, let alone the rest of the country?

“No, because it was the truth.”

Today, Tanveer works as a street motivator for IHDF, approaching children on the streets, talking about problems they may have and letting them know about the help that is available to them. He himself learnt about the organisation when he was in need of help: “There was an older boy named Tariq who was threatening me. My friend Saad — this Bengali kid — told me about Rana sahab and the IHDF. I was scared of the older boy. At night, I ran to the IHDF office, while he was running after me. Salam sahab saved me.”

What are his plans for the future?

“Bus nekian kar rahe hain. Jab tak hain, hain.”

This article was originally published in Newsline’s July 2014 issue.

The writer is a journalist and former assistant editor at Newsline.