Art as Escapism

By Sama F | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 11 years ago

A young, self-taught artist from Islamabad recently began to gain the attention of art aficionados with a series of portraits he made. “I started making portraits when a friend of mine was leaving for Sudan for humanitarian work. She really inspired me and that’s when I decided to make a series of portraits of liberal and empowered Pakistani women,” says 24-year-old Usman Ahmed, who took to the canvas just three years ago. Supermodels, singers, teachers and humanitarian workers — the women he painted belonged to various professions, but they all had one thing in common: a glamour quotient.

Ahmed’s first solo exhibition, titled Life is Not All That Flamboyant,is a departure from that glamour and instead offers a critical view on the life of cocooned privilege, partying and polo-playing in the nation’s capital, that stands in stark contrast to the lifestyle of the rest of his countrymen.

Held at My Art World, the exhibition “is a young man’s whimsical journey into the social strata that we as individuals consciously build around ourselves,” writes curator Zara Sajid.

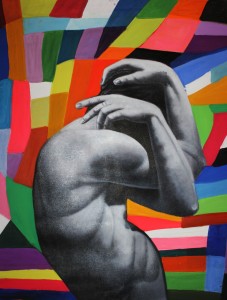

The paintings are made from the perspective of someone on the inside looking out and despite the obvious pop art influences and the use of bright colours, there is a sense of alienation that arises from the awareness of staggering class and lifestyle differences the artist observes around him, as well as a weariness of the hedonistic tendencies and the cheap (and expensive) thrills of the upper-classes.

For example, ‘Wonderland’ is a four-part acrylics on canvas series that portrays a black-and-white sketch of a woman’s wide-open mouth; an ecstasy pill sits on her tongue. Bright, neon colours in purple, orange, blue and yellow serve as the backdrop in the series, whereas the subject remains the same. The Warholian repetition portrays a sense of boredom and monotony, despite the ironic smiley-face etched on the pill. The series can be seen as a criticism of the escapism an aimless upper and upper-middle class indulge in, preferring to build metaphorical and literal walls around itself, rather than doing something ‘productive’ with the privilege they inherited. But it can also be seen as a sympathetic take — a comment on social expectations, peer pressure and the unspoken, unresolved mental illnesses of the rich and (almost) famous.

For example, ‘Wonderland’ is a four-part acrylics on canvas series that portrays a black-and-white sketch of a woman’s wide-open mouth; an ecstasy pill sits on her tongue. Bright, neon colours in purple, orange, blue and yellow serve as the backdrop in the series, whereas the subject remains the same. The Warholian repetition portrays a sense of boredom and monotony, despite the ironic smiley-face etched on the pill. The series can be seen as a criticism of the escapism an aimless upper and upper-middle class indulge in, preferring to build metaphorical and literal walls around itself, rather than doing something ‘productive’ with the privilege they inherited. But it can also be seen as a sympathetic take — a comment on social expectations, peer pressure and the unspoken, unresolved mental illnesses of the rich and (almost) famous.

This is again highlighted in ‘Trapped 1,’ in which a man, naked from the torso up, protectively covers his face with his arms. Ahmed uses cheerful splashes of colour as the backdrop to his black-and-white subjects, highlighting the disparity in their inner and outer worlds.

This review was originally published in Newsline’s July 2014 issue.

The writer is a journalist and former assistant editor at Newsline.