The Bold and the Brash

By Salwat Ali | Art | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 18 years ago

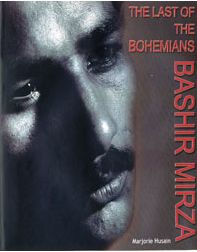

A total non-conformist, Bashir Mirza life lived entirely on his own terms and in the full glare of the media eye. His life was an open book, and a recent publication, The Last of the Bohemians by art critic Marjorie Husain, documents this ‘open book’ in graphic detail. In many instances, the descriptive accounts serve as explanatory text to Mirza’s brash public behaviour. The volume is exhaustive and lavish on both textual information and visual material; it traces the artist’s life from his home in Amritsar, where he was born in 1941, down to the millennium year 2000, when he died in his sleep in the early hours of January 15.

Husain’s introductory remarks — “Bashir Mirza was one of Pakistan’s most unpredictable, uninhibited modern artists. He was also an extremely driven man who wanted it all: fame fortune, love; most of all he craved respect” — set the tone of the book. The artist’s student years in Lahore and his adventurous life in Karachi, recounted with lively anecdotal narrative and insightful character-reading, repeatedly revolve around these initial observations. He was publicity hungry and the media of the 60s welcomed an exciting new talent to the art milieu. He once told Husain, “I don’t care what the papers say, as long as they talk about me.” Unlike reclusive artists, he and his art thrived on attention — everything BM did resonated with the complexities of a small-town boy trying to make it big. Husain’s publication has tried to capture the idiosyncrasies and moods that propelled his self-centred existence and the text winds through the complex maze of the evolving artscape here, the art fraternity BM patronised and the political and literary community he chose to be part of. For many already familiar with the audacious artist, the books sprawling text serves as a recap, but for the younger generation it’s a segment of Pakistan’s art history.

Husain’s introductory remarks — “Bashir Mirza was one of Pakistan’s most unpredictable, uninhibited modern artists. He was also an extremely driven man who wanted it all: fame fortune, love; most of all he craved respect” — set the tone of the book. The artist’s student years in Lahore and his adventurous life in Karachi, recounted with lively anecdotal narrative and insightful character-reading, repeatedly revolve around these initial observations. He was publicity hungry and the media of the 60s welcomed an exciting new talent to the art milieu. He once told Husain, “I don’t care what the papers say, as long as they talk about me.” Unlike reclusive artists, he and his art thrived on attention — everything BM did resonated with the complexities of a small-town boy trying to make it big. Husain’s publication has tried to capture the idiosyncrasies and moods that propelled his self-centred existence and the text winds through the complex maze of the evolving artscape here, the art fraternity BM patronised and the political and literary community he chose to be part of. For many already familiar with the audacious artist, the books sprawling text serves as a recap, but for the younger generation it’s a segment of Pakistan’s art history.

If BM the person was loud and conspicuous, BM the artist was just as pronounced. His densely cross-hatched pen and ink drawings were intense, but crude and raw. His Lonely Girl and Flower Flower series were sensitive and lyrical, but bold and brazen for the times, and then his King series, Sealed Lip paintings and Sydney landscapes, a cacophonic crescendo of emphatic linear expression, were as trenchant and snappy as the artist himself. Husain writes that “There is now little record of those early (pen and ink) drawings, except in photographs and the memories of those who viewed them. In later years, BM recalled his early work with wistful admiration, admitting that he had lost the powerful drive that fuelled the drawings.”

Did he digress as a painter or did he consciously opt for change of style to suit his personal priorities? It seems the artist in him gradually became subservient to the huge feeling of self-indulgence that consumed him. Alcoholism, aberrations of the flesh and the penchant for social standing were playing havoc with his psyche and, at times, reading through the book, it becomes difficult to decide who is more important — BM the person or BM the artist and his art.

The considerable photographic content in this volume, spanning a little over four decades, also centralises the artist as much as the art, perhaps more so, and the confusion continues. But today, when the artist is no more, it is his art which will speak for him — and volumes like this one will help understand the man behind the art.

No more posts to load