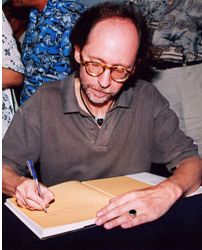

Interview: Prof Dr Wasim Frembgen

By Saad Akhtar | People | Q & A | Published 19 years ago

“There is always a controversy about who has the right to define Islam but it is all about accepting differences”

– Prof. Dr. Jürgen Wasim Frembgen

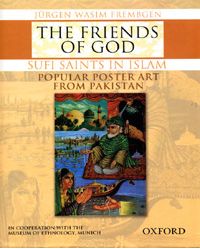

Prof. Dr. Jürgen Wasim Frembgen recently launched his book and exhibition titled The Friends of God — Sufi Saints in Islam: Popular Poster Art from Pakistan at the Goethe Institut in Karachi. He is chief curator of the Oriental Department at the Museum of Ethnology in Munich as well as lecturer of anthropology and Islamic Studies at various universities in Germany. Dr. Frembgen has been working in Pakistan since 1981 and has conducted numerous researches and published books and papers regarding Islamic, particularly Sufi, belief in Pakistan. His latest book, published by the Oxford University Press, is a collection of posters of Sufi Saints from all across Pakistan.

Q: What are your areas of interest?

A:Since the late 1970s, my areas of interest have generally been in Islam. However, since Islam has many facets and dimensions, my interest specifically has been the Sufi tradition and the veneration of Muslim saints. In addition, my work as the curator of the Museum of Ethnology in Munich, Germany, means that, because of the ‘material culture’ of the museum, I am also interested in Muslim art as well as the expression of art among the people — folk art, popular art — and the Sufi posters are in a way popular art in Pakistan.

Q: What were your reasons for being attracted to Pakistan?

A: The seeds were sown in childhood. I had a very illustrious aunt, who was also my godmother. She embraced Islam and she married a Pukhtun Popalzai from Afghanistan and travelled across the world. Since childhood, my eyes were set towards Afghanistan and South Asia.

Initially, I wanted to do fieldwork in Afghanistan but due to the Soviet invasion this was not possible. So, I shifted my focus, initially, to the mountains of Hindukush, Karakoram and the Northern Areas of Pakistan.

Since 1981, I have been coming to Pakistan every year and, in the process, I have become ‘Pakistanised.’ Step by step I was socialised into Pakistani life. I embraced Islam in 1988 and changed my second name.

Pakistan, in addition, is extraordinary and unique. It is a meeting place of cultures and it offers everything a researcher could want. I was also attracted to Pakistan because it is in many ways still unknown, as compared to other parts of the world such as India and Iran. It provides a lot of chances for new discoveries.

Q: Being a foreigner and coming here to work, what sort of barriers did you face initially?

A: It was really similar to learning like a child. You have to learn how to behave and adjust your personal habits, you have to adjust to the food and learn the language — at least to a certain extent. But adjusting to the society is always a challenge for an anthropologist doing fieldwork in a strange country.

Q: What else have you researched on in Pakistan?

A: I originally started with anthropological fieldwork in Nager, which is opposite Hunza in the Karakorams. I did a general ethnography there and worked on political history.

The second fieldwork was in Hurbund valley in Indus-Kohistan. Hurbund was a very dangerous area to do fieldwork in because there is still blood revenge going on and there is no central authority. They have their jirga system and fortified villages, with watchtowers. I was working on Islam and the social system. The Tablighi Jamaat is very active there, not the Sufi tradition.

Then I kept coming to Punjab and to Sindh-to Sehwan Sharif-to attend melas and urs to see how the common people venerate the saints in the low-land provinces of Pakistan. The Sufi shrine is a sort of aesthetic space. It’s such an interesting visual culture and it’s appealing to the senses in that you can get some taste of paradise eating the sweets and eating at the lungar. There is also the auditory aspect. You are listening to Sufi music, to qawwali and kafian. In that way, all the senses of the human body are offered a lot and the whole experience gives sukoon to people. I wanted to see what the experience of the Pakistani people was as well as experience it myself. That was my initial interest. To live with the malangs — and not in the guest-houses and air-conditioned rooms of the Sajjada Nashin -to travel in a qafila, from Shah Jamal in Lahore, for example.

Q: What problems have you faced during the research and in the time you have spent here?

A: There were hardships in the beginning during my early days in the Northern Areas, where I was starving due to the purdah system in Nager. I was not allowed to stay within the family, so I had made arrangements with a policeman to cook a bit of potatoes for me, but I went down to 48 kilograms during that time.

On the other hand, in Hurbund people showed me a lot of hospitality. They cared for me in a fantastic way and I can only praise the hospitality of people here. There were only a few ugly incidents. I remember coming back immediately after 9/11 and in 2002 there was a street urchin in Lahore who was throwing all sorts of dirty things at me. That was the single ugly incident, but that was my own fault because I was too visible as a foreigner taking a picture on that occasion.

Q: You have probably travelled more of Pakistan than most people in this country. What are your perceptions and opinions about people and places?

A: I know about the problems and I see them-over-population, pollution, crime-but despite that there is so much warmth and emotional interest in other people; in communicating with other people. There is a different quality of friendship among Pakistanis and between me and my Pakistani friends.

If there was one thing I would single out from every part of Pakistan, it would be the character of Pakistani people which I really miss in Germany. The Balochis, Pukhtun, Sindhis and Punjabis all have their own characteristics. The Punjabis have a great sense of humour and their love of food.

Q: If you had to name one of all the Sufi shrines you have visited in Pakistan, which is your favourite and why?

Q: If you had to name one of all the Sufi shrines you have visited in Pakistan, which is your favourite and why?

A: I don’t want to name just one shrine. From the point of architecture, the shrine of Mian Mir in Lahore has a fantastic serenity and tranquillity around it and my mentor- she was not my teacher but my mentor- Prof. Dr. Annemarie Schimmel, the famous German scholar, that was also her favourite shrine. But because I love the practiced forms of Islam and the vivid life of devotion, my favorite shrine is that of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan Sharif. Although from an artistic point of view it does not offer much nowadays, it has this immense energy of life around the shrine during the urs.

Q: How do Pakistani Sufi practices differ, in your opinion, from Sufi practices in Iran, Egypt or Turkey?

A: I think Sufism and Islamic mysticism is extremely vivid and colourful in Pakistan. The aspect of devotion is more emphasised here. The amount of emotional appeal is more intense than Afghanistan, Iran or Turkey. There it can be more intellectual, more sober and less colourful.

There is also the power of music. We should not forget that the most well-known and most well-respected exponents of Sufi music come from Pakistan-Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, Mubarak Ali Khan and of course, Abida Perveen, the biggest and the best Sufi voice. This aspect of music and rendering the verses of the Sufi poets is a message that Pakistan can convey to the outside world. This sort of peaceful, soft approach to religion is really very much embedded here, even if it is contested.

Q: There are those who frown upon the Sufi way of following Islam. As someone who came in as an objective observer and has embraced the faith and society, what is your opinion on this issue?

A:I know people frown upon the Sufi tradition and there are things which they don’t consider Islamic. They say it is, so to speak, not ‘true’ Islam. But there is always the question of who has the authority to say what is Islam and what isn’t. I think one should listen to the people themselves. The common people in the countryside, even among nomads, the Islam they are practicing, they are of the opinion that this is the right Islam. There are different dimensions. There is the official, normative, scriptural forms of Islam but there are also the more vernacular and popular forms of Islam as practiced at the shrines and in the villages and there is also the Sufi tradition.

Nowadays, there are very well-educated Sufis in western suits, carrying briefcases, going to London. They are members of Sufi tareeqas and silsilas. So I think the Sufi tradition is perfectly adjusted to the modern way of life. Now, we have a transnational Sufi network. In fact, this esoteric view of Islam is really at the core of Islam and the Sufis are much more into prayers and religious observances than ‘normal’ Muslims.

Q: You mentioned that there are parallels in other religions in South Asia of the sort of popular art studied in your book. Why do you think this art form is so popular despite certain conservative views of Islam in Pakistan that despise figural representations?

A:Again the orthodox and official voices of Islam have always been critical of images. There is the so-called prohibition or ban on images in normative, official Islam. They are even sometimes considered haram. In effect, the hadith addressing this issue was concerned with the mosque and other religious places where it was not allowed to exhibit any paintings or depictions of human beings.

In the history of Muslim art you have figural representations all over, on carpets, in the courtly arts of the Mughals, Safawids and Ottomans, you have all these depictions of human beings in popular expressions of faith. Be it Islam or any other religion, there was always a demand on the popular level to make the saint more apparent, to bring him closer to the simpler minds of the people.

It was always controversial and there were also periods in Muslim history where there was more tolerance towards images. Then the Taliban were destroying the Buddha images in Bamiyan and there was a hue and cry raised against that.

There is always a controversy about who has the right to define Islam but it is all about accepting differences. I am just exhibiting the posters and researching them because they are part of a certain aspect of popular Islam. Not all the Muslims in Pakistan share these beliefs and, of course, it is more in the disprivileged social classes in Pakistan, the common people in the streets, they purchase and use these posters as a tabarruk to express their personal religious identity.

Q: As a professor and teacher, what advice would you give students planning on doing similar research?

A:If I’m addressing a class of German students, I would advise them to try and convey sympathy and empathy. I think this is the order of the day: Muslims and people in western countries all have to realise that in this global age we all have to live with differences.

People like Baba Bullay Shah have given us examples and models in the way that people from different religions should sit together on equal terms. They should not develop hate and animosity and they can all benefit from meeting each other and exchanging views in a liberal way. That, in short, is my philosophy.