Text and Tradition

By Sumbul Khan | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 18 years ago

Commenting on the place of Arabic calligraphy in medieval Islamic architecture, Erica Dodd suggests that when the language of a script is unfamiliar to its audience, the word begins to operate as an image. It is perhaps for this reason that calligraphy as an art form continues to hold currency in the Pakistani art circle. Although it is still considered an Islamic art form, its contemporary practise is not an exercise in promoting a particularly Muslim national identity any more, as it was in the incipient years of Pakistan’s formation. Rashid Arshad’s recent show at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture is especially interesting in the way it acknowledges the continual flux in the Pakistani audience’s relationship with calligraphy. The paintings draw on a range of aesthetic borrowings, with no embedded religious or nationalistic agenda.

Commenting on the place of Arabic calligraphy in medieval Islamic architecture, Erica Dodd suggests that when the language of a script is unfamiliar to its audience, the word begins to operate as an image. It is perhaps for this reason that calligraphy as an art form continues to hold currency in the Pakistani art circle. Although it is still considered an Islamic art form, its contemporary practise is not an exercise in promoting a particularly Muslim national identity any more, as it was in the incipient years of Pakistan’s formation. Rashid Arshad’s recent show at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture is especially interesting in the way it acknowledges the continual flux in the Pakistani audience’s relationship with calligraphy. The paintings draw on a range of aesthetic borrowings, with no embedded religious or nationalistic agenda.

The show opens with a nod to the Quranic manuscript tradition, where canvases become enlarged manuscript pages covered with the Maghrebi script seen in surviving pages from Ummayyad Spain. Our interaction with Arabic calligraphy in Pakistan begins on religious terms and it seems befitting to recall the splendour of an Islamic dynasty that was devoted to embellishment.

Defying historicity, set on white between bold black lines, a line of Arabic script looks like a typographic experiment. Each letter is enunciated meticulously as if it were a peek into the sketchbook of a present-day designer rather than a leaf from a sixteenth-century muraqqa.

Gradually, these pages begin to lose their letters to the margins. In one piece, we are left with a brilliant cerulean square in the centre as its writing flees upward to the white ground surrounding it. Their absence in the blue space functions as an invisible presence, speaking of unwilling banishment. In another piece, the letters seem to charge in from a red margin into a black rectilinear space. The ascenders and descenders of the alphabet encroach menacingly onto the slate, claiming their hold on it.

These paintings, part of the “In Essence” series, hark back to the modernist phase in Pakistani painting where calligraphy reduces itself to Greenbergian essentials — alphabets, colour, and negative space, relinquishing its meaning as a string of words.

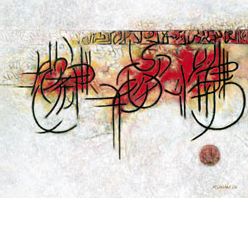

Much like the endeavours of the Bengal School which looked eastward to define its aesthetics, a couple of pieces evidence the commingling of Japanese Sumi painting and Perso-Arabic khattati. Worked horizontally from right to left, using the Perso-Arabic script in Sumi gesticulation, the pieces are installed vertically to mimic their Japanese antecedents, which are read from top to bottom. This is the prime instance where language is rendered redundant in favour of its visual appeal.

Much like the endeavours of the Bengal School which looked eastward to define its aesthetics, a couple of pieces evidence the commingling of Japanese Sumi painting and Perso-Arabic khattati. Worked horizontally from right to left, using the Perso-Arabic script in Sumi gesticulation, the pieces are installed vertically to mimic their Japanese antecedents, which are read from top to bottom. This is the prime instance where language is rendered redundant in favour of its visual appeal.

Other untitled works employ the alphabet as a mark, where the constant repetition of the mark creates a texture or pattern. The colour modulations across the canvas resist three-dimensionality and hence are reminiscent of De Kooning’s abstract expressionism. In one such instance, the chosen alphabets appears to be la-ilaa. The phrase is an extraction from the Muslim Kalima, meaning “there is none,” but in its repeated juxtaposition it turns into a wall of heiroglyphs. It is as if the painting mocks the viewer who comes to it looking for a coherent sentence, grappling for some meaning when there is none. In fact, as opposed to the previous religiously inspired works which affirm the existence of a God, the painting even with its calligraphic content, seems to deny that very existence in the most wonderfully subversive way.

Post-modern de-contexualisation continues in the black on white paintings which amplify the weight of the script such that it turns into an architectonic form. Arshad confesses his fascination for architecture and flirts with the possibility of turning typographic forms into elevations of actual buildings. With Frank Gehry’s Bilbao antics occupying their space in functional reality, it does not seem quite so outrageous a notion to consider. In the Islamic context, word and building were inextricably connected where buildings professed the word, albeit decoratively. If buildings were to become words, particularly in Pakistan, what words would they be, and would they actually bring us to the original religious associations of calligraphy?

In a way the show takes us through the developmental trajectory from the traditional to the contemporary, and yet in another, it really only brings us full circle to reconnect us with the tradition from which we departed. It resolves the tension between text and image by using them as interchangeable entities. Preoccupation with the written word, be it religious text or history, obfuscates due appreciation of what is meant to be a conglomerate of both.