The Countdown Begins

By Naveed Ahmad | News & Politics | Published 19 years ago

For the students of crisis diplomacy, Iran’s nuclear standoff offers some invaluable lessons. Tehran does not seem to run out of options while pursuing her national interest and national pride. While developments gained pace with the referral of Iran’s nuclear standoff to the United Nations Security Council, the signing of a tentative agreement with Russia to establish a joint uranium enrichment venture has put the hawks in the western world on the back foot.

Though details of the Iran-Russia agreement are secret, it is seen as a breakthrough in talks on a US-backed Kremlin proposal aimed at easing concerns that Tehran wants to build nuclear weapons.

Earlier, Iran’s foreign minister, Manouchehr Mottaki, said there were several issues to be resolved before his country agreed to a proposed Russian solution to the standoff over his nation’s nuclear ambitions.

It remains unclear if Iran will entirely give up enrichment at home and completely rely on Russia-enriched uranium to produce electricity. Iran’s deputy nuclear chief, Mohammad Saeedi, told journalists that the deal would be off if the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) referred Iran to the Security Council on March 6.

US National Security Adviser Stephen Hadley cautiously commented on CNN’s ‘Late Edition,’ “In any of these arrangements, the devil is in the details. We’ll just have to see what emerges.”

On the other hand, just a day after the Iran-Russia deal, IAEA Director General Mohamed ElBaradei said Iran has begun feeding uranium gas into centrifuge ‘cascades’, that it has been using a 10-machine cascade from February 15 and is testing a 20-machine version.

Enrichment is a process that involves feeding uranium gas through cascades of centrifuges. When purified to low levels, the result is reactor fuel, but the process can be extended to make the fissile core of a nuclear bomb.

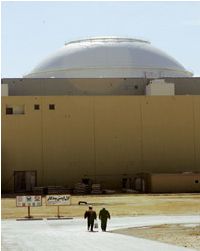

Iran’s nuclear energy programme has become controversial in recent years with some critics saying that Iran does not need nuclear energy in view of its vast oil and gas reserves. Tehran, however, claims that the western opposition to its nuclear energy programme is politically motivated, since there was no opposition to the Bushehr nuclear power plant project when it started with German support before the 1979 revolution. Iran maintains that if it can use nuclear power to meet some of its domestic energy needs, it will be able to export more oil to generate foreign currency revenues.

In early February, the IAEA board of governors, including Russia, voted to report Iran to the Security Council without suggesting any immediate action.

Meanwhile, the Iranian officials have stated that the Bushehr nuclear power plant is 90 per cent complete. Tehran plans to install two more 1,000-megawatt nuclear power plants at the site. According to an Iranian official, the tenders for the construction of the other nuclear power plants will be announced in March. The Iranians hope that the Russians will come forward for the construction of the plants.

China, a commercial partner of Iran, is pressing for an amicable resolution of the row. Beijing sent Vice Foreign Minister Li Guozheng to Tehran to offer help in resolving the standoff. China is in the process of finalising its own agreement with Iran to develop another large oil field.

Around the same time, Iranian Foreign Minister Manouchehr Mottaki dashed to Tokyo for talks with his Japanese counterpart. Undoubtedly, Tokyo has high stakes in the matter given the fact that it imports much of its oil from the Middle Eastern nation, and UNSC sanctions may gravely affect its economy — fears shared by China as well.

In 2004, Japan inked a two-billion-dollar contract to develop Azadegan in southwestern Iran, considered one of the biggest untapped oil reserves in the world. Japan fulfils 15 per cent of its oil needs through Iranian resources. Tokyo signed the pact in defiance of United States opposition. Iran currently provides one-sixth of Japan’s oil imports. Now, in the worst-case scenario, Japan may find it impossible to resist US demands that it pull out of the Azadegan project.

It is learnt that Mottaki sought help from his Japanese counterpart Taro Aso and Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi to win greater concessions from Russia as it discusses its modalities with Moscow.

Iran has the world’s second biggest proven oil reserves after Saudi Arabia and the second biggest gas reserves after Russia. Iran’s geo-strategic position and its already existing network of pipelines make it a key actor in the energy world. International and domestic factors have obstructed optimal use by Iran of its energy resources since the 1979 revolution.

Revenues from oil exports, projected to reach at least 45 billion dollars by March 2007, according to reports in the Iranian press, fund about 50 per cent of Iran’s annual budget.

Iran supplies about 5 per cent of the world’s oil supply. In February 2006, an oil ministry official put crude production at 3.5 — 4 million barrels per day (bpd), a figure that could be increased by 1 million bpd.

Iran’s oil and gas sector suffers from under-investment because of US sanctions, which have been in force for more than two decades. The curbs have not only barred US companies from investing in Iran, but have also served as a disincentive to other countries’ firms and multinationals due to the threat of secondary sanctions approved by the US Congress in 1996.

Despite initial success in the Iran-Russia talks, the nuclear stand-off has reached a new level after its referral to the UN Security Council. Without wasting much time, Tehran withdrew cooperation over snap inspections and threatened to resume all its enrichment activities.

IAEA officials have leaked to the western media the fact that Iran possessed a document on moulding highly enriched uranium into a nuclear warhead and said that the document was shared with the agency by the Iranians themselves.

Iran has accused the Pakistani nuclear scientist Dr A.Q. Khan of handing over the document without ever being asked for it, while he was discreetly transferring some nuclear technology. Western officials, however, don’t buy this explanation.

Technically speaking, Iran stands by its right to make its own fuel under the terms of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). However, it is required to open the facilities to IAEA inspection.

The western nations believe that Iran is not to be trusted as its programme has been behind the veil since the 1979 Islamic revolution took place. US nuclear think tanks suspect that Iran is, at most, five years away from developing a full fledged nuclear bomb. Tel Aviv, however, believes that Iran is capable of building a nuclear bomb within a year.

The harshest allegations against Tehran emanate from Paris where French Foreign Minister, Philippe Douste-Blazy, said Iran’s nuclear activity is a cover for a clandestine weapons programmme.

The Iranian foreign ministry official termed nuclear weapons against the spirit of Islam, quoting a fatwa by the country’s lead Ayatollahs. In fact, in 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini had ordered the closure of the Bushehar nuclear project, terming it un-Islamic.

The Iranians believe that it is an inalienable right to produce nuclear energy and their country has the right to do so under the NPT. Iran believes that the Iranian nuclear programme is being judged on political grounds rather than the technical considerations that the UN agency (IAEA) is expected to take into account.

Tehran has repeatedly threatened to quit the NPT if pressure by western states, particularly the US, continues to increase. Legally, Iran’s case is conceded as strong, both in terms of NPT Statutes and the Additional Protocol. The IAEA, to date, has not been provided any factual evidence by the United States that Iran has an ongoing nuclear weapons programme.

Geo-politics determines the United States’ stance on Iran’s nuclear programme. Iran, as a regional power in the making, reinforced with a possible ‘basement nuclear bomb,’ could knock out all the props of United States strategy in the Middle East, namely, Israel , Turkey and Pakistan.

There is a view that fears of an attack from Washington are the key factor behind Iran’s drive to attain a self-reliant nuclear policy. Paul Pillar, who wrote the CIA’s National Intelligence Estimates (NIEs) on Iran from 2000 to 2005 as the national intelligence officer for the Near East and South Asia, told the wire service Inter-Press Service, “Iranian perceptions of threat, especially from the United States and Israel, were not the only factor, but were in our judgment, part of what drove whatever effort they were making to build nuclear weapons.”

There is a view that fears of an attack from Washington are the key factor behind Iran’s drive to attain a self-reliant nuclear policy. Paul Pillar, who wrote the CIA’s National Intelligence Estimates (NIEs) on Iran from 2000 to 2005 as the national intelligence officer for the Near East and South Asia, told the wire service Inter-Press Service, “Iranian perceptions of threat, especially from the United States and Israel, were not the only factor, but were in our judgment, part of what drove whatever effort they were making to build nuclear weapons.”

Pillar said the dominant view of the intelligence community in the past three years has been that Iran would seek a nuclear weapons capability, but analysts have also considered that a willingness on the part of Washington to reassure Iran on its security fears would have a significant effect on Iranian policy.

Pillar said one of the things analysts have taken into account is Iran’s May 2003 proposal to the Bush administration to negotiate on its nuclear option and its relationship with Hezbollah and other anti-Israel groups as well as its own security concerns.

The 1991 Gulf War, in which US forces destroyed most of the Iraqi army, caused the Iranians to become much more concerned about U.S. military intentions, apprehending that the same thing could happen to Iran, according to some scholarly analyses of Iranian thinking.

In early 2002, a secret Pentagon report to Congress on its ‘Nuclear Posture Review’ identified Iran as one of seven countries against which nuclear weapons might be used “in the event of surprising military developments.” The report was published in the Los Angeles Times on January 26, 2002.

Five days later, Bush referred to Iran in his State of the Union address as being part of an ‘axis of evil,’ along with Iraq and North Korea. “By seeking weapons of mass destruction,” he said, “these regimes pose a grave and growing danger.”

At the same time, Iran’s aspirations to revive its centuries-old dominant position in the region has also been a key factor in the quest for nuclear technology. Pakistan’s nuclear programme and eventual testing was seen to undermine the Iranian role in the region.

Similar to what it did with the Iraqi nuclear plant in the suburbs of Baghdad, Tel Aviv has an elaborate secret plan to destroy the Iranian one as well. It is no secret that Israeli plans include a combined air and ground attack on targets in Iran when its patience runs out. The Israeli government’s core cabinet group has already issued what is termed as ‘initial authorisation’ for an attack in its meeting in the Negev desert.

The Israeli forces have used a mock-up of Iran’s Natanz uranium enrichment plant in the desert to practice destroying it. Their tactics include raids by Israel’s elite Shaldag (Kingfisher) commando unit and airstrikes by F-15 jets from the 69 Squadron using bunker-busting bombs to penetrate underground facilities.

US officials have openly confirmed considering military strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities should the issue become deadlocked at the United Nations. With Iraq already under American occupation, reaching Iran ‘s heartland has become much easier for the Israeli daredevils.

The surprise win by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in the 2005 Iranian presidential election gave a monopoly on power to the religious conservatives controlling all of the elected and appointed institutions that govern the country.

It is hard to say how Rafsanjani would have dealt with the nuclear stand-off, yet one can safely assume the position would have been more or less the same. The only difference would have been the rhetoric: what his predecessor would have tackled quietly through diplomatic channels, Ahmadinejad is carrying out with a rhetorical flourish.

It is hard to say how Rafsanjani would have dealt with the nuclear stand-off, yet one can safely assume the position would have been more or less the same. The only difference would have been the rhetoric: what his predecessor would have tackled quietly through diplomatic channels, Ahmadinejad is carrying out with a rhetorical flourish.

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who was a mayor of Tehran in the spring of 2003, is perceived as a determined zealot rather than a mature political leader in the west. Since his election, Ahmadinejad has taken a tough stand on a number of foreign policy matters.

A PhD in traffic and transport from Tehran’s University of Science and Technology, the sitting Iranian president actively participated in the 1979 revolution.

Ahmadinejad enjoys enviable popularity in the country. Only mass support took him to the echelons of power, as he did not spend any money on his presidential campaign. His party skilfully used mosques to run his election campaign and eventually succeeded in the bid.

Iran’s geography has not changed, its demographics have not changed and its Shia religious majority has not changed. What has changed significantly since 1979 is its political system and governance. Clearly, a prime reason for the United States vehement opposition to Iran’s nuclear programme is its present regime.

While the United States’ doctrine of regime change may not work here, the American intelligence services continue to monitor the political situation in Iran, maintaining close contact with the Iranian community in the US. The largely pro-Shah expatriates are ready to go to any lengths to promote the downfall of the revolutionary government.

However, for the time being, Washington will put more pressure on Dr ElBaradei, who has an Iranian wife, to provide all the right reasons to punish Tehran for its defiance. In an interview with a US magazine, he said that in spite of three years of investigation, “I am not yet in a position to make a judgment on the peaceful nature of the [nuclear] programme.” He added, “We still need to assure ourselves through access to documents, individuals [and] locations that we have seen all that we ought to see and that there is nothing fishy, if you like, about the programme.”

He said that if they (Iran) have the nuclear material and a parallel weaponisation program along the way, they were really not very far from a weapon.

That is what the United States and its allies would like to highlight in the March 6 report to the UNSC. Despite progress on the Iran-Russia route, ElBaradei, in the same interview, called for prohibition on Iran’s right of enrichment for peaceful purposes because “… of the lack of confidence in your programme and because the IAEA has not yet given you a clean bill of health, you should not exercise that right.” The IAEA director general also said, “Diplomacy is not just talking. Diplomacy has to be backed by pressure and, in extreme cases, by force.”

The west has so far failed to restrain Iran from expanding its economic and military relations with the significant players in world politics. The Iran-Pakistan-India gas pipeline is set to become a reality as both Islamabad and New Delhi have defied US pressure to thwart the project. Similarly, Russian, Chinese and Japanese investment deals, along with their oil dependence on Iran, add to Tehran’s diplomatic options.

IAEA testimony in the UNSC, on March 6, is likely to put Iran on the receiving end after its denial of access to the agency. However, gaining Russian and Chinese support for any action would be far from easy for the US and its other European allies. Iran is expected to keep Russia engaged to deny its support to the US-led camp. Similarly, China would stick to its policy of exploiting diplomatic options.

In the wake of a stand-off at the UNSC, the Israelis and the neoconservative American leadership may consider carrying out military strikes against Iran. It goes without saying that the context of the Israeli clandestine operation against an Iraqi nuclear plant in the early ’80s and that of Iran are starkly different. Iraq was not prepared for such an attack, while Iran is well equipped with its long-range missiles, aircraft and strong leadership. Moreover, world public opinion is already opposed to any such action, following the fiascos in Iraq and Afghanistan. More importantly, the world may not quietly stand by and watch such a strike on Iranian nuclear assets. Another clandestine operation by Israel may invite an intense and bloody response at home from Hamas-led Palestinians and diplomatic battles at the United Nations with the Muslim world and countries such as Russia, China and even Japan.

Analysts tend to agree that the Russian proposal offers a last chance to achieve a peaceful resolution to another complex dispute. Meanwhile, the Americans should not overestimate their military might, nor should the Iranians count on their diplomatic skills and bargaining position.