Test of Will

By Amir Mir | News & Politics | Published 20 years ago

In the wake of the London bombings and the fact that at least three suspects were of Pakistani origin, General Pervez Musharraf has once again given a deadline to religious seminaries or madrassahs across Pakistan to get themselves registered with the Wafaqul Madaris or face the music.

In the wake of the London bombings and the fact that at least three suspects were of Pakistani origin, General Pervez Musharraf has once again given a deadline to religious seminaries or madrassahs across Pakistan to get themselves registered with the Wafaqul Madaris or face the music.

General Musharraf said nothing new in his July 25 televised address to the nation. He reiterated his government’s resolve to confront head-on the menaces of terrorism and extremism, and outlined a number of steps he intends to take. However, most of these measures have been announced before, and by none other than the General himself in his historic January 2002 speech.

The Musharraf government actually launched its madrassah reform project in 2002 with a total allocation of 5.7 billion rupees for the project. However, three years down the road, only the meagre amount of 514.5 million rupees has been spent toward this end. Now the implementation of the December 2005 deadline for the registration of madrassahs will be a test of Musharraf’s resolve.

Certainly it will be a difficult undertaking since the concerned authorities would have to register an average of 133 schools per day to ensure completion of the process in time. Of the approximately 40,000 religious seminaries currently operating in Pakistan, only about 10,000 are registered with the government, whereas the remaining 30,000 are non-registered. The madrassahs are registered under two different Acts in Pakistan — The Societies Act 1925 with the Registrar Societies that is headed by the Directorate of Industries, and The Trust Act, 1982. The registered madrassahs are regulated by five central boards representing different sects/sub-sects including Barelvi, Deobandi, Ahle-Hadith, Shia and the Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan. However, not a single madrassah has been registered after Musharraf’s July 21 speech because of an undue delay in amending the outdated Societies Act-1925. As the Act is being revised by the government, the Religious Affairs Ministry has barred the auqaf departments from registering any of the seminaries. The Religious Affairs Ministry headed by Federal Religious Affairs Minister Ejazul Haq maintains that under the Societies Act 1925, the registration of madrassahs was a provincial subject and without amending the Act, a centralised mechanism of madrassah reforms cannot be established.

Therefore, the relevant departments have been directed not to register any madrassah unless the Societies Act 1925 is amended. Resultantly, the relevant departments are not entertaining the applications for registration of madrassahs. But the Religious Affairs Ministry insists that amending the Societies Act 1925 is necessary since the existing Act does not cover the regulation of seminaries, audit of funds they receive and teaching of modern science, computer education and technical subjects. “Under the existing Act, we can only register marakaz (centres), but it does not provide any mechanism to regulate madrassahs,” says Wakil Ahmed Khan, Secretary, Religious Affairs Ministry.

Meanwhile, until — or unless — the government’s proposed reform plan is implemented, Pakistan will inevitably continue to pay a heavy price for status quo. While no religious seminary in Pakistan is prepared to confess that the three London suicide bombers ever contacted them, the Pakistan government has itself admitted that all three men visited Pakistan between November 2004 and February 2005. Muhammad Siddiq Khan (30) and Shehzad Tanweer (22) are said to have stayed in Lahore or other cities of the Punjab, and Haseeb Hussain (18), the youngest of the bombers, is believed to have visited Karachi. During their stay at different seminaries across Punjab the bombers reportedly learnt how to make explosives based on instructions known to feature in Al-Qaeda manuals. And six months after their return from Pakistan, they allegedly committed the acts of terrorism in London.

The changing face of the madrassah and the proliferation of these schools in Pakistan can be directly traced to Zia-ul-Haq’s rule when the students of the seminaries were indoctrinated with a jihadi ideology and sent to Afghanistan to fight the Soviet occupiers. The same war-hardened zealots were also used by Zia’s military establishment in Indian-occupied Kashmir. With state patronage the numbers of the institutions multiplied and today there are reportedly close to 50,000 such schools within Pakistan, as compared to only 245 at the time of independence in 1947.

Although he offered no source for his estimate, in an analysis paper for the Brookings Institute in 2001, P.W. Singer quoted a figure of 45,000 madrassahs in Pakistan. However, in April 2002, Dr. Mahmood Ahmed Ghazi, the Federal Minister of Religious Affairs, put the figure at 10,000, with 1.7 million students. Such is the lack of implementation of the madrassah reform plan, that to date the federal government does not have a reliable figure for the actual number of seminaries in the country. In fact, the Religious Affairs Ministry and the Ministries of Interior and Education have each quoted different figures.

Since President Musharraf’s reform plan was first announced, the federal government has been providing financial assistance to religious schools with the purported purposes of modernising textbooks, including secular subjects in the curricula and introducing computers in the classroom. In 2001-02 a total of 1,654,000 rupees was distributed among madrassahs . As the total number of students in all the seminaries is in the vicinity of 1,065,277, this would work out to 1.55 rupees per student per year, but not all seminaries accepted the assistance. Additional aid of 30.5 million rupees has been promised for providing computers and changing the syllabi in 2003-04, which would amount to 28.6 rupees per student if all madrassahs availed of the funding. However, since many seminaries do not accept financial aid from the government, the money allocated will not be distributed to the students in the proportion stipulated in the disbursement formula.

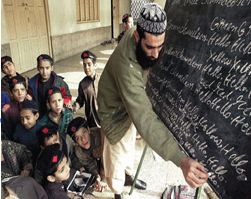

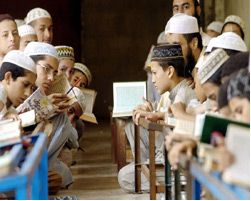

Madrassahs generally do not charge tuition fees. While they do charge an admission fee, this sum does not usually exceed 400 rupees. Thus these schools attract very poor students who would not be able to afford any other kind of education. The student body in these seminaries ranges from a few students to several thousands each. And most teach an extreme version of Islam, usually a combination of Wahabism, a puritanical form of Islam originating in Saudi Arabia, with Deobandism, a version from the Indian subcontinent that is essentially anti-west. With little or no state supervision, it is up to individual schools to decide the curricula. However, most provide only religious subjects to their students, focusing on rote memorisation of Arabic texts to the exclusion of basic skills such as simple math, science or geography.

The campaign to reform the country’s deeni madrassahs was launched by Musharraf in a bid to fight extremism in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 terror attacks on the United States. Musharraf’s military government enacted two laws to control the madrassahs. The first was aimed at bringing the madrassahs into the mainstream by introducing secular subjects in the curricula taught at these schools. This ordinance, called the ‘Pakistan Madrassah Education (Establishment and Affiliation of Model Deeni Madaris) Board Ordinance 2001′ was promulgated on August 18, 2001.

According to the Education Sector Reforms, three model institutions were subsequently established: one each at Karachi, Sukkur and Islamabad. Their curriculum includes English, Mathematics, Computer Science, Economics, Political Science, Law and Pakistan Studies. However, these institutions were not welcomed by the ulema. Later, another law was introduced to control the entry of foreigners in the madrassahs and to keep a close check on them. This law — the Voluntary Registration and Regulation Ordinance 2002 — has also been rejected by most of the madrassahs which want no state interference in their affairs.

While embarking on several other initiatives to combat zealotry and liberalise the educational system, the Musharraf administration announced a number of measures to make deeni madrassahs participate in the modernisation programme. These reforms included a five-year, one billion dollar Education Sector Reform Assistance (ESRA) plan to ensure the inclusion of secular subjects in the syllabi of religious seminaries, and a 100-million-dollar bilateral agreement to rehabilitate hundreds of public schools by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

However, most of the religious leaders and Islamist organisations have rejected outright all the government legislation requiring religious seminaries to register and broaden their curricula beyond rote Quranic learning. Under the reform programme, drafted on the advice of the Bush administration and financed by USAID, special government committees were constituted to supervise and monitor educational and financial matters and policies of deeni madrassahs in the country. Most of these schools are sponsored by leading religious parties, including the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, the Jamiat Ulema-Pakistan, or the Jamat-e-Islami Pakistan. Many others, meanwhile, are affiliated with jihadi groups which preach an extremist ideology of religious warfare.

However, most of the religious leaders and Islamist organisations have rejected outright all the government legislation requiring religious seminaries to register and broaden their curricula beyond rote Quranic learning. Under the reform programme, drafted on the advice of the Bush administration and financed by USAID, special government committees were constituted to supervise and monitor educational and financial matters and policies of deeni madrassahs in the country. Most of these schools are sponsored by leading religious parties, including the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, the Jamiat Ulema-Pakistan, or the Jamat-e-Islami Pakistan. Many others, meanwhile, are affiliated with jihadi groups which preach an extremist ideology of religious warfare.

In January 2004, the International Crisis Group (ICG) report titled, ‘Unfulfilled Promises: Pakistan’s Failure to Tackle Extremism’ further heightened American fears. The report stated: “The failure to curb rising extremism in Pakistan stems directly from the military government’s own unwillingness to act against its political allies among the religious groups. Having co-opted the religious parties to gain constitutional cover for his military rule, Musharraf is highly reliant on the religious right for his regime’s survival.”

The ICG report observed that Pakistan’s failure to close down madrassahs and to crack down on jihadi networks has resulted in a resurgence of domestic extremism and sectarian violence. “The government inaction continues to pose a serious threat to domestic, regional and international security,” read the report.

Less than a year later, in December 2004, a report produced by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) presented to the American Congress pointed out: “Although General Musharraf vowed to begin regulating Pakistan’s religious schools, and his government launched a five-year plan to bring the teaching of formal or secular subjects to 8,000 willing madrassahs, no concrete action was taken until June of that year, when 115 madrassahs were denied access to government assistance due to their alleged links to militancy… Despite Musharraf’s repeated pledges to crack down on the more extremist madrassahs in his country, there is little concrete evidence that he has done so.

“As matters stand today, most of the madrassahs remain unregistered, their finances unregulated, and the government has yet to remove the jihadist and sectarian content of their curricula. Observers speculate that Musharraf’s reluctance to enforce reform is rooted in his desire to remain on good terms with Pakistan’s Islamist political parties, which are seen to be an important part of his political base.”

However, a World Bank-sponsored working paper published in February 2005 had a dissenting view. It stated that “enrolment in the Pakistani madrassahs, that critics believe are misused by militants, has been exaggerated by media and a US 9/11 report.” The study claimed that less than one per cent of the school-going children in Pakistan attend madrassahs, and the proportion has remained constant in some districts since 2001.

The study titled ‘Religious School Enrolment in Pakistan: A Look at the Data’, conducted by Jishnu Das of the World Bank, Asim Ijaz Khwaja and Tristan Zajonc of Harvard University and Tahir Andrabi of Pomona College, also sought to dispel general perceptions that enrolment was on the rise, saying: “We find no evidence of a dramatic increase in madrassah enrolment in recent years.” The funding for the report was provided by the World Bank through the Knowledge for Change Trust Fund.

The World Bank study claimed that western media reports were highly exaggerated in terms of the number of student and religious schools in the country. “The figures reported by international newspapers such as The Washington Post, saying there was 10 per cent enrolment in madrassahs, and an estimate by the International Crisis Group of 33 per cent, were not correct. It is troubling that none of the reports and articles reviewed based their analysis on publicly available data or established statistical methodologies,” said the study.

However, the ICG’s South Asia Director, Samina Ahmed, challenged the findings of the World Bank study. She responded on March 11, 2005: “The authors (of the World Bank report) have insisted that there are at most 475,000 children in Pakistani madrassahs, yet Federal Religious Affairs Minister Ejazul Haq says the country’s madrassahs impart religious education to 1,000,000 children.”

Samina Ahmed asserted that the World Bank findings were directly at odds with the Ministry of Education’s 2003 directory, which said the number of madrassahs had increased from 6,996 in 2001 to 10,430. She added that the madrassah unions themselves had put the figure at 13,000 madrassahs with the total number of students enrolled at 1.5 to 1.7 million.

Questioning the methodology of the World Bank study, she said: “The trouble is that the authors based their analysis on three questionable sources: the highly controversial 1998 census; household surveys that were neither designed nor conducted to elicit data on madrassah enrolment, and a limited village-based household educational census conducted by the researchers themselves in only three of 102 districts.”

Ahmed said the 1998 census was not only out of date as the authors themselves admitted, but their 2003 educational census was also of little value because it was based on a representative sample of villages, suggesting that the madrassahs were mainly a rural phenomenon. She quoted a 2002 survey conducted by the Institute of Policy Studies which found that a majority of madrassah students came from backward areas. “If the findings of the World Bank study were to be taken at face value, then Pakistan and the international community had little cause to worry about an educational sector that glorified jihad and indoctrinated children in religious intolerance and extremism,” the ICG director concluded.

The conflicting reports aside, the Musharraf regime’s failure to reform the country’s 10,000 religious seminaries three years after he first pledged to do so, does not inspire confidence in his recent promise to get the job done. Given the overwhelming focus on Pakistan following the London attacks, the need to make good on this promise has, however, never been more imperative.