State of the Union

By Najmuddin A. Shaikh | News & Politics | Published 22 years ago

The furore created by the remarks that Ambassador Nancy Powell reportedly made during her address to the American Business Council in Karachi on January 24 (“Pakistan must ensure that its pledges are implemented to prevent infiltration across the Line of Control and end the use of Pakistan as a platform for terrorism”), is a measure of the naive and misinformed notion of the US-Pak relationship entertained by the media and certain political circles in Pakistan

Our Information Minister possibly, influenced by the angry comments in the press and MMA spokesmen, said, “Either the U.S. envoy had been misquoted or her statement was aimed at appeasing India.” Ambassador Powell, herself, appears to have taken the damage control measure of not posting the text of her speech on the Embassy or the Karachi Consulate-General website (it is noteworthy that the latter site carries the transcript of the two most recent speeches the US Ambassador to India has delivered on Indo-US relations) and thus allowed the State Department spokesman to say in his press briefing of January 24 that “she made some remarks that I was told were rather misquoted.” But he then went on to add an explanation that could not have been found very palatable in Islamabad: “She made remarks in a speech in Karachi where she echoed the remarks of President Musharraf in January last year, when he said that Pakistan would not allow its territory to be used for any terrorist activity anywhere in the world. That has been a pledge that we have taken seriously and something we have continued to work with Pakistan on… On the subject of infiltration, as you know, we said infiltration has gone down and come back up somewhat. My understanding is she said yes, that President Musharraf has made assurances that it will stop, and that is something that we work with him on. We do believe infiltration should stop completely and that is an issue that we do continue to work on with the government of Pakistan.”

Pakistani representatives may wish to argue that the pledge on terrorism and infiltration were both made in the context of India and that if there has been any slippage the blame for it should be laid at the door of the Indians for not having reciprocated the courageous gesture made by President Musharraf and for making even further demands on Pakistan. The truth of the matter, however, is that the use of Pakistani territory for terrorist activity is an issue between the USA and Pakistan that predates the terrorist attack on the Indian Parliament. The Indians seized upon this attack and the international outrage it provoked as a golden opportunity to make common cause with the international community and to bring pressure to bear on Pakistan, but the USA was worried about this even earlier.

The American State Department’s annual report on “Global Patterns of Terrorism” for the year 2000 said that the centre of terrorist activity had shifted from the Middle East to the area covered by Afghanistan, Pakistan and northern India (this was owed only in part to the concerns about the safe haven the Al-Qaeda had found in Afghanistan).

Earlier, and particularly after the kidnapping and killing of American and European tourists in Indian-held Kashmir in 1995, report after report in the western press about terrorist incidents in the west quoted official sources as saying that investigations established a trail leading back to Pakistan and Afghanistan. In August ’01, about a month before 9/11, deputy secretary Armitage addressing the press in Australia said, “the United States is not interested in Pakistan becoming more under the influence of Afghanistan…. There has to be a way out for Pakistan… We are going to try and play an effective role”.

In an earlier interview to The Hindu (18-06-01), Armitage had maintained that the so-called great (US-Pak) relationship of the past was, in fact, a false one because in the first instance “it was built against the Indo-Soviet axis and then latterly it was against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. So we did not have a policy for Pakistan, we had a policy with Pakistan directed against something else…. what we are desirous of is for our Pakistani friends to try and develop a relationship about Pakistan.” In essence what Armitage was saying was that while in the past there had been “cold war” reasons for relations with Pakistan now the American interest was to use its relationship with Pakistan to help it become a moderate, stable, democratic state which could resist the pull of the Taliban ideology.

By August 2001, it was known that the sanctions imposed on both India and Pakistan, after the nuclear explosions of May ’98, were to be lifted. It was also clear that this step was primarily India-driven, since the equally damaging but Pakistan-specific sanctions imposed because of the military takeover in October ’99 were not being lifted. This decision had been made, perhaps after debate, because the Bush administration had in mind not only the opposition it would face in Congress, but also that the maintenance of these sanctions would give them additional leverage against an economically-strapped Pakistan. The State Department spokesman made this clear in his comments on the announcement of the election schedule on August 14 when he said, “US sanctions triggered by the military coup in October of 1999 cannot be lifted until our President determines that a democratically elected government has taken office”.

9/11 changed this situation. After President Musharraf agreed to join the coalition and to make facilities available to the Americans for their attack on the Taliban the sanctions were lifted, generous economic assistance was offered and tentative steps taken to suggest the restoration of a more cordial relationship. I have always felt that most parts of the establishment, and in particular, the President himself regarded 9/11 as an opportunity to sever the umbilical cord that had tied Pakistan to the Taliban and that there was confidence that no major upheaval would follow. But this was not the American perception.

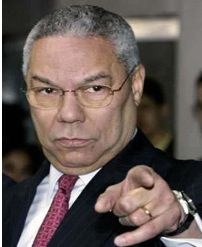

In an eight part series of articles appearing in the Washington Post from January 27, 2002 to February 3, 2002, Bob Woodward gives a rather racy account of the decision-making process in the American government in the crucial days after September 11. He says that after it had been decided that action was to be taken against the Taliban, “Powell had told Bush that whatever action he took, it could not be done without Pakistan’s support. But the Pakistanis had to be put on notice… Squeezing Musharraf too hard was risky, given the potential for fundamentalist unrest inside his country, but Powell believed they had no other choice.” It is now well-known that a list of seven demands were communicated first by deputy secretary Armitage to General Mahmood of the ISI, who was in Washington at that time, and then to President Musharraf by Secretary Powell. They were accepted. But to my mind the key element was the apprehension in the American mind that the potential for fundamentalist unrest in Pakistan made squeezing Musharraf too hard a risky proposition.

It is probable that the relative ease with which the Pakistani public accepted the government’s change of stance may have reassured the Americans that the danger of fundamentalism in Pakistan had been exaggerated. More likely, however, it only served to confirm the view of the more discerning among the Americans who believed that, in the absence of patronage from official circles, fundamentalist forces were containable. These observers were probably also convinced that if patronage continued, extremism was a monster that would soon go out of the control of its manipulators.

In the perception of many Pakistanis the victory of the MMA was attributable to the ham-handed discrimination against the Pakhtuns in Afghanistan by the American-led coalition and by the needless civilian casualties — primarily Pakhtuns — in the war against the Al-Qaeda and the Taliban. In the eyes of the Americans, far too much was done officially to promote their unity, to facilitate the participation of their otherwise ineligible candidates in the elections in the elections, and to avail of the official media to publicise their campaign. In Pakistani eyes, Pakistan has done more than its share in capturing and handing over Al-Qaeda leaders and operatives — the majority of the inmates of Guantanamo Base are those apprehended by Pakistan — and in acting upon intelligence provided by the Americans in this regard. In American eyes, this only shows how many sympathisers Al-Qaeda had in Pakistan and how many more must still be there.

A January 25 report in the Washington Post filed from south -east Afghanistan discussing the situation of American forces in that area says, “At the foot of the mountains, in easy viewing range through binoculars, lies the Pakistani town of Angur Hada. Mike and his military superiors in Afghanistan are convinced that, like other villages and towns farther inside Pakistan, it is often filled with al Qaeda and Taliban fighters….. Fifteen months after the start of their campaign to topple the Taliban and destroy al Qaeda, they still face an invisible but determined enemy, capable of slipping into Afghanistan from apparent havens in Pakistan to attack those they see as infidels and invaders”

Today US-Pak relations are being driven in Washington by only two major considerations: (i) The assistance needed from Pakistan in the short term to seek out and destroy in Afghanistan and in Pakistan’s tribal areas and urban centres the remnants of the Al-Qaeda and the Taliban. (ii) Reverse in the short, medium and long-term, the transformation of Pakistan into a permanent haven for extremist Islamic elements. Rightly or wrongly there is the perception in Washington that in pursuit of goals they have set for themselves many elements in Pakistan, including those in positions of power are willing to risk allowing such a transformation to come about. They do not believe the extremist groups that have plagued Pakistan internally, and against whom the Pakistan government has ostensibly set its face, can be separated from those engaged in pursuing a more noble cause.

A stable Pakistan was an American objective even in 1971 when its intervention was decisive in preventing the Indians from proceeding with their planned attenuation if not destruction of Pakistan’s armed forces. It is an even greater imperative today when it has a nuclear capability. At that time the United States was concerned about a balance of power in South Asia. Today that consideration remains important but in current policy formulation is far less significant than the nightmarish possibility of extremists gaining power and control in Pakistan. We may dismiss such fears as being far from reality but we must recognise that these perceptions drive policy in a terrorism-obsessed Washington.

There was no departure, therefore, from the brief in the remarks attributed to Ambassador Powell. It was instead a reminder not only of the need for Pakistan to honour the pledge President Musharraf had apparently offered, but also of steps the Americans believe Pakistan needs to take to set its internal house in order and to prevent “nightmares” becoming realities. In a bid to keep temperatures from rising, the State Department spokesman has said that this subject is not on the agenda of the Kasuri-Powell meeting, but one can be sure that our new foreign minister will be given the message that in asking for this the Americans are not putting forward an Indian demand but a request of their own.

Similarly, one can be almost certain that the current visit of Gen. Tommy Franks, who was taking time out from the preparations of the campaign against Iraq, has been undertaken to press for greater cooperation from the Pakistani armed forces to eliminate the safe havens in Pakistan for the forces that are helping to keep south-east Afghanistan in turmoil.

It would be wise for Pakistan’s policy-makers to assume that it is through the prism of these two American objectives that all other facets of the US-Pakistan relationship will be viewed. On Kashmir the Americans are advocating the resumption of the Indo-Pak dialogue, but they also believe that such dialogue should aim at restoring normalcy in relations, which in turn would allow for the Kashmir issue to be addressed peaceably. Richard Haas, the State Department’s policy planner, in making this point in his speech to the Confederation of Indian industry went on to add, “I believe I have an appreciation for the depth of feeling Pakistanis have for Kashmir. Nevertheless, I would discourage

Pakistanis from allowing their focus on resolving the Kashmir dispute to block progress on other issues that involve India and that hold out the promise of an improved bilateral relationship. I have worked on regional conflicts for almost three decades — be it Cyprus, Northern Ireland, or the Middle East. And if there is one lesson I have learned, it is that the inability to resolve big issues should not stop progress on the little ones. The path to large breakthroughs is often paved with agreements on small issues.”

Of course this is what the Indians have been saying and is what they are now pressing with renewed vigour. Prime Minister Vajpayee who in previous years had talked in his famous musings of abandoning the “beaten track” and constructing a “new architecture of security in South Asia” has now said that Pakistan must forsake its insistence on the centrality of Kashmir in an Indo-Pak dialogue and instead reach agreement on other issues, thus helping create the atmosphere in which the Kashmir issue can be amicably resolved. Indian Foreign Minister Sinha has reiterated the same theme, quoting as an example the development of Sino-Indian relations while setting aside temporarily the contentious Sino-Indian border dispute.

One can say, perhaps with a degree of truth, that the Americans in their pursuit of a strategic partnership with India have adopted the Indian line, but one should also calculate that the Americans want to signal that the method Pakistan has adopted to keep Kashmir central in Indo-Pak relations is no longer acceptable.