Across the Divide

By Massoud Ansari | News & Politics | Published 22 years ago

Till a few years ago, every Sunday scores of villagers in the Keran sector of the Neelam valley used to gather on both sides of the Neelam River to “meet” their dear ones on either side of the river. The villagers still recall the heart-rending scenes at these meetings which came to an end after tensions intensified in the region in the wake of the Kargil crisis.

“Ammi, it’s me. Can you see my son, who is now a big boy?” says Shabbir Ahmed, who recalls running along the bank of the river, holding his three-year old son in his arms, to show him to his grandmother on the other side. He also remembers his mother wiping away her tears when she saw his son and how he had tried to console her, “Don’t worry Ammi we are all doing fine. Things will change soon and we will be able to meet again…” Even today Shabbir’s eyes are filled with pain and hope. He is confident that things will change and he will be united, once again, with his family across the divide. “I know what has not changed in the last 50 years will not change overnight, but I’m sure I will be able to meet my parents before I die,” he said.

When these meetings were allowed, the villagers used to exchange gifts and throw letters to each other, wrapped around small stones, as they were literally a stone’s throw away from each other. Shouting across the river, they would discuss the weather and fishing prospects. But they could never meet. There are schools on both sides of the river, and children from both schools recognise each other, and though they shout out to each other, they cannot play together. They can see each others’ houses, but cannot visit. These divided families are separated by only a few 100 metres but they might as well be on the other side of the world. With both the Indian and Pakistani armies eyeball to eyeball at the border, a reunion is virtually impossible.

While there are hundreds and thousands of families who continue to suffer the pain of separation after they were divided in 1947, the villagers in the Keran sector, were only separated in the 1965 war. The villagers say the Indian troops occupied the part of their village located on the other side of the river, which was later declared as the Line of Control (LoC) and sliced their village in half, separating parents from children and brothers from sisters.

Though for the Pakistani and Indian armies it is the Line of Control that is a political divide, for the inhabitants on both sides it is a line of blood and tears. “This man-made LoC has not only divided territory but has separated mothers from their children and sisters from their brothers. It has divided the hearts, emotions and relationships in hundreds and thousands of families in Kashmir,” says a local.

Many of the young men take turns in calling the Azaan in both the village mosques over the loud speakers hoping that their voices will be heard by their mothers and sisters across the border. “Every time I say the Azaan I feel like I am talking to my mother,” says a villager who tries to control his emotions, but the pain is clearly etched on his face. “If the sound of my voice carries across the river, at least my parents will know that I’m still alive,” he says.

Though every villager in the surrounding Neelam valley has his/her own story of separation to tell, one particular tale shook every one in the village. During one of the across-the-river meetings a young woman was talking to members of her family on the Indian side of the divide. Her younger brother could not control his emotions and jumped into the fast flowing river to go to her. Her mother, already separated from her only daughter, tried to jump into the river to go after her son, but she was caught by the Indian soldiers. Every one saw her being beaten up but were helpless to stop them. In the meantime, the brother managed to cross the river safely but never met his parents again. According to the villagers, they have no idea what happened to the old lady as she was never seen again on the river banks.

Those living near the border suffer whenever tension escalates in the region. Most of these villagers find it difficult to even travel on roads located near the LoC because they always come under fire. Since roads close to the LoC are closed for traffic most of the time, buses drop the villagers far from their homes, leaving them to walk for two hours to reach their respective villages. “We stop here in the day and go to our villages by foot at night,” says Arif Mughal, a villager, carrying rations for his family. The villagers say that because of this continuous firing they are facing acute shortage of food and medicine, while the prices of daily essentials have gone up.

In many villages there are bunkers built close to every house and whenever the firing starts, the villagers immediately move into these bunkers for shelter. “Whenever the firing starts, everyone runs to the bunkers. This is a routine for all the sick, the old and even the children,” says Abdullah Abbasi of Chikoti town, which is located just few hundred metres away from the LoC. Almost every villager in the surrounding area has lost a loved one to Indian firing. At least 20 civilians are believed to have been killed in the last six months alone, in the Leepa valley. The pockmarks of enemy-shelling mark houses and schools in all these villages.

Fifty-year-old Mohammed Shabbir Abbasi, who has been a witness to many confrontations across the LoC, lost his wife to cross-border firing only a few weeks ago. After a lifetime of living under constant tension, he is desperate for peace. “I have been witness to three generations either killed by shelling, or fallen prey to mines and killed and maimed. Now I want all this to end,” says Shabbir.

“They always fire at civilians unprovoked, and our response is always professional and measured, meant to quiet their guns,” says a proud Brigadier Iftikhar Ali Khan, commander of the Chikoti sector. He maintains they don’t fire at villages across the border, only targeting the bunkers of the ‘enemy’ because they know that most of the people living near the border on the Indian side are Muslims.

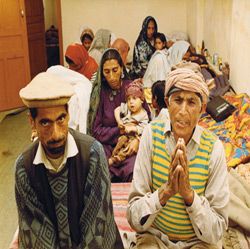

Prior to the 1989 insurgency in Jammu, families on either side of the LoC regularly visited each other, especially at weddings or deaths. Now it is almost unthinkable to cross the border not only because of troop deployment but also because of the deadly landmines which are spread on both sides. “The mines have been laid all along the border without any planning and are even more than those in Afghanistan,” says Lieutenant Colonel Syed Masood Raza, the commander of Nuseri sector along the LoC. According to him, even if the dispute between the two countries is settled, it would take years to clear the mines, which were laid by the armies to check infiltration. As a result many villagers who have tried to cross the hostile borders have either died or been maimed and now most villagers have almost given up the idea of sneaking across to the other side. The refugee camps on the Pakistani side are full of refugees with missing limbs. Eight-year-old Sajjad didn’t know how he lost one of his legs. “I was just three years old when I was injured in a mine blast and I really don’t know what happened,” he said. According to his parents who came from Amrohi village in the Kupwara sector and chose to illegally cross into Pakistan five years ago, “There were a couple of villagers who were travelling with us who were also hurt, but our son was the most seriously injured,” says Sajjad’s mother.

Thirty-year-old Ahmed, a refugee who teaches at a school in Manik Paya camp near Muzaffarabad, lost one of his feet during his journey to Pakistan. He fled his village near Kupwara district in Indian-held Kashmir a few years ago after he came under suspicion because of his association with the freedom fighters. A student in Srinagar University, Ahmed was picked up by law enforcing agencies but was released after he was interrogated for a couple of days. Soon after he was told that his house was to be raided. Sensing that he would be arrested, Ahmed crossed over into Pakistan leaving his mother, father and three brothers and sisters behind. “It took me four days to reach Pakistan,” Ahmed said recalling his torturous journey through thick jungles, hostile terrain and the fast flowing Neelam river.

Thirty-year-old Ahmed, a refugee who teaches at a school in Manik Paya camp near Muzaffarabad, lost one of his feet during his journey to Pakistan. He fled his village near Kupwara district in Indian-held Kashmir a few years ago after he came under suspicion because of his association with the freedom fighters. A student in Srinagar University, Ahmed was picked up by law enforcing agencies but was released after he was interrogated for a couple of days. Soon after he was told that his house was to be raided. Sensing that he would be arrested, Ahmed crossed over into Pakistan leaving his mother, father and three brothers and sisters behind. “It took me four days to reach Pakistan,” Ahmed said recalling his torturous journey through thick jungles, hostile terrain and the fast flowing Neelam river.

To avoid being caught, most immigrants travel under the cover of night and shelter in villages along the way during the day. “I was not scared of the wild animals in the jungles, or any of the other dangers I encountered. My only fear was being caught by the Indian army,” says Ahmed. When he had almost reached the border, Ahmed stepped on a landmine and lost one of his feet. “As soon as the mine went off the Indian army started firing towards the blast and I was lucky that I was not hit,” he said. Ahmed crawled towards his destination, bleeding profusely from his wounds. “I kept creeping for another half an hour or so before I fainted. You know, one can only endure all this once you see death staring at you,” Ahmed said with sardonic smile on his face, maintaining that only those who undergo these perilous journeys can understand what the refugees have been through to get to Pakistan. When Ahmed regained consciousness he found himself surrounded by unknown villagers who had wrapped his feet in bandages. They later handed him over to the local police where he was interrogated by various agencies. “This is routine practice with anyone who crosses the border and one is allowed to live in the refugee camps once they are cleared by the agencies,” Ahmed said.

For the last couple of years Ahmed has been living all alone in the camp and has had no news about the rest of his family. He doesn’t even know if they are alive. Given the ongoing tension he cannot write or phone. “Writing or phoning my family will only jeopardise their safety since all letters and phone calls are screened and monitored,” he said. However he is still hopeful that one day he will be reunited with his family. “I will not marry in the absence of my parents. I want my sisters to sing songs and dance at my wedding,” he said as he limped to a nearby mosque to say his prayers.

While Ahmed remains optimistic, there are many others who have lost all hope of ever seeing their families again and are suffering from various mental disorders. Aijaz, a refugee who crossed the border some eight years ago, has recently been admitted in the Psychiatric ward of Abbas Institute of Medical Sciences, in Muzaffarabad. Even though he married a refugee girl three years ago, he could not overcome his acute depression. “I don’t know, my brain has stopped working. I had a life in my village and was living with my parents. Now I think that I have lost everything and have nothing to live for,” he said.

The majority of the refugees in the camps get a 700-rupee monthly stipend each, but find it almost impossible to find employment. As a result, most go hungry, sit idle all day, waiting in vain to be reunited once again with their families on the other side. Those who are lucky sometimes find daily wages work in the cities to supplement their incomes, but for most even working as cheap labour is difficult and their suffering increases during the harsh winters.

Dr. Khwaja Hamid Rashid, a psychiatrist, said the refugees can be divided into two different groups, those who opted to come to Pakistan after 1947 and after the 1965 war, and the others who were forced to evacuate their families after the insurgency broke out in Indian-held Kashmir in 1989. “I have observed that the second group is suffering from the worst mental traumas, while the first group is not as prone to mental disorders.” He gave an example of one of his recent patients, who is suffering from severe mental disturbance. “In fact he migrated to the Pakistani side of Kashmir some 30 to 40 years ago and is well-settled and was doing fine until he learnt recently that his mother has died in Indian-held of Kashmir. Because of the prevailing tension he is unable to even say Fateha (prayer) at his mother’s grave,” the doctor said.

Another patient was admitted to Dr. Khawaja’s clinic after he learnt that one of his sisters had been raped. “I cannot really express his mental trauma and his feelings,” Dr. Khwaja said. He said most of these refugees suffer from adjustment disorders, uncertainty about their future, and the pain of separation from their families. The most affected are normally the women.

A study carried out by the doctors at the Abbas Institute of Medical Sciences, Muzaffarabad revealed that out of the 534 patients in the psychiatric clinic, 167 had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The study states, “Factors included stress of migration (32.9 per cent), death of family members by atrocities of law enforcement agencies (26.9 per cent), emotional and psychological torture (22.8 per cent) and destruction of native home, property or livelihood (19.2 per cent).”

Observers, however, feel that currently the lack of people-to-people contact is leading to heightened levels of suspicion on both sides and exacerbating an already tense situation. “Allowing citizens to move freely between hostile countries helps break down the stereotypes that are often generated because of isolation and fear-mongering,” says one political observer. “After all when the Berlin Wall can be broken and when even North Korea can allow citizen exchanges with South Korea, then surely India, the world’s largest democracy, and Pakistan cannot object to a peaceful interchange between their citizens…”