Soul Music

By Abdulrahman Rafiq | Arts & Culture | Published 20 years ago

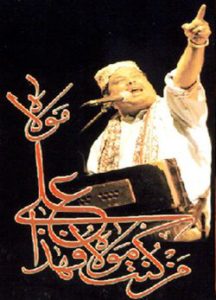

Music has, no doubt, the power to transcend all barriers of language and culture. This was borne out by the response to a qawwali event sponsored by Stanford University in California, starring Farid Ayaz and humnava, descendants of the classic qawwal Munshi Raziuddin who traced his family’s lineage back all the way to Tan Sen.

Music has, no doubt, the power to transcend all barriers of language and culture. This was borne out by the response to a qawwali event sponsored by Stanford University in California, starring Farid Ayaz and humnava, descendants of the classic qawwal Munshi Raziuddin who traced his family’s lineage back all the way to Tan Sen.

Their performance was part of the “Pan Asian Music Festival, South Asia.” The event was presented by the Department of Musicand the Asian Religions and Cultures Initiative. The programme included Sufi Rock with Salman Ahmad and Junoon, a tribute to A.R.Rahman, performances by Katrik Sheshadr on Sitar and Swapam Chaudhuri on tabla, Carnatic morning Ragas by Sanjay Subramanium and the Stanford Symphony Orchestra.

Jindong Cai, Associate Professor of Music at Stanford wrote, “…the best way to understand other peoples is through their art and their culture. Unfortunately, though our world is ever more globalised, these are often overlooked in favour of reporting on problems, conflicts and differences.”

The festival was one step in the right direction, an effort to enable a sharing of experience.

Among the highlights was a two-day symposium on Sufi music (Theme: South Asian Qawwali and Debates on Music in Islam). Unquestionably, the most exciting event of the entire symposium was the Farid Ayaz Qawwali performance on the night of February 13. The auditorium was packed with Indian and Pakistani desis, and students and faculty of the campus and beyond.

Regula Qureshi, author of Sufi Music of India and Pakistan: Sound, context and meaning in Qawwali, gave a pre-concert talk explaining, as best she could, the wonder of the qawwali tradition. But as lovers of this form of devotion well know, no words can capture the mystical quality of ecstasy that hides, lurks and predictably explodes in the hands of craft masters, such as these descendants of the great Munshi Raziuddin himself.

Farid Ayaz introduced his family’s tradition and gave a brief talk on the history of Qawwali, Amir Khusro’s role and its relationship to the Hindu traditions of Sanskrit sounds and letters. His three brothers, nephews and others astounded the audience with their brilliant performance. Abu Muhammad, the group’s second lead and harmonium player, touched the hearts of the audience with his gentle, yet powerful voice. Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus, Christians and Jews alike were soon offering dollar bills to the qawwals.

It was a stiff stage-like setting — a far cry from the relaxed gardens and drawing rooms of home — but the magic of Farid Ayaz and humnava came through loud and clear.