Islam’s Real Enemies

“The Grand Mufti began by thanking the Fuhrer for the great honour he had bestowed by receiving him.” Thus begins an official Nazi account of a meeting on November 28, 1941, between Adolf Hitler and Haj Amin Al Husaini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, the most influential leader of the Palestinian Arabs at the time, who lived in Germany during the Second World War. The Greater German Reich, Al Husaini told the German leader, was “admired by the entire Arab world.”

According to this document, the Grand Mufti assured Hitler that: “The Arabs were Germany’s natural friends, because they had the same enemies as had Germany, namely the English, the Jews, and the Communists. They were therefore prepared to cooperate with Germany with all their hearts and stood ready to participate in the war.” All Husaini sought from the Fuhrer at this juncture was an official Nazi declaration in support of Arab national aspirations.

Hitler responded that although he was willing to issue a private assurance, the time was not ripe for an official declaration at this point in Germany’s “life and death struggle with two citadels of Jewish power: Great Britain and Soviet Russia.” That time would come once the German armies reached “the southern exit from Caucasia” and “forced open the road to Iran and Iraq through Rostov.” Once “Germany’s tank divisions and air squadrons had made their appearance south of the Caucasus, the public appeal requested by the Grand Mufti would go out to the Arab world.”

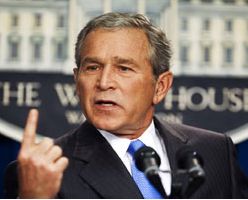

Fortunately for the Arab nations — and, for that matter, the rest of the world — it never came to that. Hitler’s armies got bogged down and perished in the Soviet Union. A contrary outcome may indeed have led to the establishment of surrogate fascist regimes in parts of the Middle East. An unholy alliance between Muslim organisations and the Nazis would, in all likelihood, have bred ideologies considerably more pernicious than what George W. Bush last month labelled “Islamic fascism.”

The simple-minded US president intended it as an all-encompassing description covering potential terrorists in Britain, Iraqi insurgents, the resurgent Taliban in Afghanistan and Hezbollah in Lebanon. Chances are that the incoherence inherent in such a broad application of the epithet escaped his attention. It is even more likely that he is unaware of the exclusively left-wing antecedents of the indiscriminate use of the term “fascist”: radicals in the west tended to be liberal in applying it to a variety of perceived foes, particularly in cases where a degree of repression was involved.

Writing in The Wall Street Journal last month, the conservative philosopher Roger Scruton attributed the first use of the term Islamo-fascism to Maxime Rodinson, the late French Marxist scholar who devoted much of his life to a (largely sympathetic) study of Islam. According to Scruton, Rodinson coined the term to describe the ascendancy of the ayatollahs in Iran following the overthrow of the Shah in 1979. Scruton also reminds us that Rodinson (who died two years ago) believed that terrorism ostensibly aimed at the greater glory of Islam was based on a misreading of the scriptures — a conclusion that one can only hope most Muslims would agree with.

Islamo-fascism regained currency in the aftermath of September 11 thanks to the efforts of writers such as Christopher Hitchens, an erstwhile left-wing “contrarian,” who thereafter made common cause with the American neo-conservatives. At the same time, it’s worth noting that after the rather better-known American writer Norman Mailer announced that in his opinion the US had entered a pre-fascist state, some commentators pointed out that the prefix was probably superfluous.

Does this mean we are witnessing a clash of fascisms?

No, not quite. Notwithstanding Bush’s innumerable shortcomings, he is no Hitler. By the same token, comparisons with the Fuhrer contributed little to our understanding of Slobodan Milosevic and Saddam Hussein, nor are they particularly meaningful descriptors when applied to Hassan Nasrallah or Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (notwithstanding the latter’s tendency to infuse his rhetoric with neo-Hitlerian zeal when he speaks of Israel and the Jews). Certainly, elements — sometimes strong ones — can be located in the conduct of affairs by the ayatollahs, the Taliban and the Saudi regime. The same could be said of Zia-ul-Haq’s Pakistan as well as Chile under Pinochet. Some of the tactics Israel adopts in maintaining its occupation of Palestine seem to have Nazi antecedents, and the neo-cons in Washington veer in the same direction when they favour military conquest as the primary means of ideological (and economic) domination.

The use of the term “Islamic fascism” is intended in part to create the impression that the so-called war on terrorism is as worthy an endeavour as was the struggle against the Nazi hordes more than 60 years ago. Intentionally or otherwise, it also serves to reinforce the idea of some sort of an umbilical link between fascism and Islam. This insinuation can be refuted without denying that there are extremely serious problems associated with Islam at this point in history.

These problems did not surface out of the blue on September 11, 2001. There can be little question, however, that they have sharply been exacerbated in the intervening five years. A primary cause (albeit not the only one) has been the dangerously misguided Anglo-American reaction. The toppling of the twin towers through a spectacular act of indiscriminate violence placed the US in an unusual position: on higher moral ground vis-a-vis a ruthless adversary. There could have been no better platform for intelligently and proportionately combating the Al Qaeda menace, notwithstanding whatever role the US may have played in its creation.

But that was not to be. The Bush administration exhibited indecent haste in slithering off the high moral ground and, shortly thereafter, sank further into an ethical, legal and strategic morass of its own making through the gratuitous invasion of Iraq. It almost seemed as if the aggression was a calculated attempt to exacerbate the tendency towards violent militancy among some Muslims.

But that was not to be. The Bush administration exhibited indecent haste in slithering off the high moral ground and, shortly thereafter, sank further into an ethical, legal and strategic morass of its own making through the gratuitous invasion of Iraq. It almost seemed as if the aggression was a calculated attempt to exacerbate the tendency towards violent militancy among some Muslims.

The resurgence of western imperialism offers only a partial explanation of what motivates Muslim suicide bombers who target innocent civilians, and cannot conceivably serve as justification for their deeds. It’s nonetheless highly unlikely that their numbers would have grown so rapidly in the wake of 9/11, but for the clumsiness and banal cruelty of subsequent actions by the US and its allies.

In the wake of last month’s arrest of two dozen young people in Britain on the suspicion that they were plotting to blow up to a dozen commercial airliners out of the sky by smuggling liquid explosives aboard, a bunch of Muslim legislators and community leaders wrote to Tony Blair, suggesting that drastic changes in his government’s foreign policy would go a long way towards calming down the hot-heads among British Muslims. This, in turn, would sharply reduce the likelihood of further attacks along the lines of those perpetrated in London on July 7 last year. A number of commentators responded by rubbishing the idea that British foreign policy should be dictated by a religious or ethnic minority: it should be changed, they said, not to appease Muslims but simply because it is wrong.

That’s a sensible enough point. A large number of Britons vehemently oppose their government’s policies, not least its subservience to the US and its role in Iraq. The overwhelming majority of them, including most Muslims, do not seek to register their protest by blowing themselves up in a crowded plane, train or bus.

There are no easy explanations for the attitude of the bloody-minded minority. A “fascist” tag does not appear to be much more helpful than the common neo-con caricature of fanatics seeking early access to paradise (and the 72 virgins that supposedly await each of them therein) through the murder of as many “infidels” as possible. Impressions of this sort are underlined by the recasting of murderous suicide missions as “martyrdom operations” and by the citing of Quranic verses as a purported justification.

There are no easy explanations for the attitude of the bloody-minded minority. A “fascist” tag does not appear to be much more helpful than the common neo-con caricature of fanatics seeking early access to paradise (and the 72 virgins that supposedly await each of them therein) through the murder of as many “infidels” as possible. Impressions of this sort are underlined by the recasting of murderous suicide missions as “martyrdom operations” and by the citing of Quranic verses as a purported justification.

Robert Pape, an expert on suicide bombings and the author of Dying To Win, who has studied the phenomenon in forensic detail at least in the Lebanese context, contends that the association of religious fervour with such attacks is misleading. Less than one-fourth of those who carried out suicide missions in southern Lebanon during Hezbollah’s campaign against Israel’s 18-year occupation could be described as fundamentalists, he says; the majority hailed from leftist organisations and three of them were Christians. In Pape’s view, most suicide bombings are motivated by a secular desire to end a perceived or real military occupation. He notes that the most systematic practitioners of the tactic are the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam — who are, of course, never described as Hindu terrorists, any more than Hitler and Mussolini were labelled Christian fascists.

It wouldn’t be surprising if comparable research in the occupied Palestinian territories yielded similar results, given that the resistance movement there directly confronts an occupying power. However, the relationship between the British state and second-generation Pakistani immigrants on the outskirts of London is rather different, and it is hard to believe that anyone other than Muslim fanatics would have the audacity to cold-bloodedly target fellow Britons.

Last month’s arrests in Britain understandably spawned a great deal of scepticism: the terrorist acts they were allegedly planning were described as imminent, even though not one of them had booked his or her passage on a trans-Atlantic (or any other) flight, and the security checks introduced at Heathrow and other airports verged on absurdity. Although last year’s atrocities on the London underground are still fresh in people’s minds, so is the false “intelligence” cited as justification for invading Iraq. And it is well known that the perpetuation of fear is essential to maintaining an atmosphere conducive to the pursuit of imperialist goals — which helps to explain, among other things, why American intelligence sources insisted that the thwarted plan involved blowing up airliners over key cities in the US, whereas British agencies insisted that as far they could tell, the idea was to cause explosions over the Atlantic.

It doesn’t necessarily follow, though, that the whole affair was a hoax. The imminence aspect was evidently an exaggeration but, unfortunately, it is perfectly possible that the plot — whatever its details — was more than a figment of someone’s imagination. The arrests followed a year-long surveillance, with key evidence apparently provided by Pakistan.

A more or less inevitable side effect of the London plot will be increased suspicion of Britons of Pakistani origin and the reinforcement of racist stereotypes that underscore decades of poor integration.

It has widely been suggested that the extremism that distorts and defames Islam ought to be countered by Muslims with broader minds. In some cases, this is easier said than done: moderates are understandably wary of being targeted as apostates. On the other hand, the fact that a substantial proportion of British Muslims believe, for instance, that violence against civilian targets is sometimes justified, calls for an urgent response.

Ideally, the most important component of this response should come from within Islam — and not just in Britain. There is much talk of the religion’s teachings being distorted by fanatical preachers and poseurs. A strictly selective approach to any faith’s scriptures can, of course, produce damaging and dangerous perversions. The difference is that whereas literal interpretations of the Bible, for instance, attract ridicule and derision from significant numbers of Christians, including influential priests and scholars, Muslims are relatively disinclined to challenge the tablighees and other tormentors who ignore the compassion and the mercy supposedly inherent in the message of Islam.

Such people are, for all practical purposes, the enemies of Islam. Why can’t there be fatwas against them? Why can’t there be fatwas against those who preach or exalt terrorism? Why can’t it be made clear that the God who speaks through the Quran cannot possibly condone the murder of innocents? Why are so many aalims and mullahs reluctant to unequivocally denounce abhorrent cultural practices that tend to be associated with Islam, even though they may have nothing whatsoever to do with the faith: among others, so-called honour killings, female circumcision, and the ridiculous custom of women being “married” to the Quran?

Chances are that the United States will come to its senses once the majority of Americans are convinced that their nation’s role in the world is crying out for a drastic readjustment. By the same token, Israel will find peace only when most of its citizens realise that the ideal of living in harmony with its neighbours entails concessions capable of satisfying Palestinian aspirations.

“Islam is in danger” was a paranoid catchcry long ago, when the greenback helped to sustain the madrassahs and communism and secularism were deemed to be the enemies-in-chief. It rings more true today, when Islam is indeed in danger — not so much from its purported enemies as from within, from bigots intent upon hijacking it for nefarious purposes and, perhaps, exploding it over the Atlantic.

Mahir Ali is an Australia-based journalist. He writes regularly for several Pakistani publications, including Newsline.