House of Cards

By Zahid Hussain | News & Politics | Published 23 years ago

Disarray and confusion continues to grip the government of Prime Minister Mir Zafarullah Khan Jamali after he scraped through to the top slot by a razor-thin margin of one vote after the military engineered the defection of ten opposition members. Within one week of its inception, the coalition has turned into a minority in the National Assembly, fighting for its survival in the face of an aggressive and powerful opposition. The parting of ways with the Mutahida Qaumi Movement, the crisis of the formation of a government in Sindh and the opposition MMA taking over the administration in the key North West Frontier province, have further exacerbated Jamali’s woes. The self-effacing Jamali, currently presiding over a fractured coalition comprising several wrangling groups and defectors, is confronted with a situation not experienced by any other civilian leader. “It is like a rudderless ship with no policy direction,” says a senior government official. The conflict between the National Assembly and the military president over the changes in the constitution remains unresolved, raising serious questions about the sustainability of the new setup.

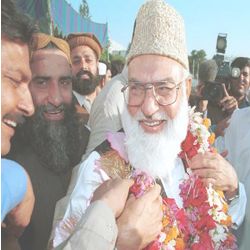

The defection of 10 PPPP members, that salvaged the situation for Jamali after protracted negotiations between the PML-(Q) and the MMA, broke down a day before the National Assembly was convened. The talks apparently collapsed as the MMA stuck to its crucial demand that President Musharraf give a firm date for stepping down from the post of chief of army staff. According to highly placed political sources, General Musharraf had agreed to drop the National Security Council, but was not prepared to concede to the MMA’s main demand. The Islamic leaders said they just wanted the President to give a tentative date for the shedding of his military uniform . “We cannot accept a President in uniform,” declared Qazi Hussain Ahmed. It was difficult for the MMA leaders to compromise on this central demand because of pressure from the hard-line newly elected legislators.

The military authorities, however, pulled out the required number of votes by manipulating a split in the PPPP. Jamali’s “victory” was made possible after President Musharraf, in a highly controversial move, suspended the ban on floor-crossing allowing opposition members to switch sides. The division between the PPP and the five-party MMA alliance also “played a major role in helping the pro-military leader to secure a majority.”

It is quite apparent that Faisal Saleh Hayat, Rao Sikandar and some other PPPP defectors were in contact with the military authorities even before the elections. Faisal, a former federal minister, has been charged by NAB for defaulting on the repayment of loans worth millions of rupees from nationalised banks and had spent months in jail, making him extremely vulnerable to pressure. He was initially offered the foreign ministry, but preferred the interior portfolio. It is still not clear whether NAB will pursue the corruption cases against the new interior minister; a senior general walked up to him during the oath-taking ceremony to congratulate the “loan defaulter” for what he described as a “courageous move in the national interest!”

Rao Sikandar, an old PPP stalwart, is a personal friend of President Musharraf and was on the list of favourite candidates prepared by Tariq Aziz and the ISI prior to the polling. It is not surprising that he has been given the important defence portfolio. The other pillar of the fractious coalition government is Aftab Ahmed Sherpao, a former chief minister of NWFP and now the head of his own faction of the PPP. Wanted on several charges of corruption, Sherpao fled the country after the military take-over and was allowed to return only after he struck a deal with the military authorities. A retired major, Sherpao’s contacts in the army top brass helped his political rehabilitation. He was cleared of most corruption charges, through the courts in record time to facilitate his participation in the elections and was even considered for prime minstership at one point.

Despite all this manipulation and horse-trading engineered by the intelligence agencies, Jamali barely managed to scrape through. His election came as a relief to President Musharraf who clearly wanted a pliable prime minister in place. However, Jamali’s controversial one-vote majority raises doubts about the long term survival of the new civilian government. The soft spoken, stoutly-built Jamali has been the military’s preferred candidate for Pakistan’s top civilian job because of his pliant nature. A tribal leader from Pakistan’s most backward region, southwestern Balochistan, Mr. Jamali has a reputation of being an establishment figure who is unlikely to take any stand against the country’s powerful military President. He is also Pakistan’s first elected prime minister from Balochistan.

Despite all this manipulation and horse-trading engineered by the intelligence agencies, Jamali barely managed to scrape through. His election came as a relief to President Musharraf who clearly wanted a pliable prime minister in place. However, Jamali’s controversial one-vote majority raises doubts about the long term survival of the new civilian government. The soft spoken, stoutly-built Jamali has been the military’s preferred candidate for Pakistan’s top civilian job because of his pliant nature. A tribal leader from Pakistan’s most backward region, southwestern Balochistan, Mr. Jamali has a reputation of being an establishment figure who is unlikely to take any stand against the country’s powerful military President. He is also Pakistan’s first elected prime minister from Balochistan.

An easy-going and experienced politician, Mr. Jamali has served three brief terms as chief minister in his native province, most recently in 1996. He has also been a federal minister in the military regime of the late General Ziaul Haq in the mid-1980s. His friends call him “Jabal” (mountain) — a nickname earned as a young man for not crying after a bad injury during a hockey match.

It is quite apparent that the ostensibly civilan government will work under General Musharraf’s presidential shadow. Jamali has promised to continue President Musharraf’s economic and foreign policies saying that Pakistan has benefited from military rule. He pledged Pakistan’s continued support for the US-led war on terrorism, “Pakistan has become a frontline state, and will remain one,” said Jamali. “Pakistan is going ahead as a respectable country.”

In an address to the nation a day before Jamali’s election, President Musharraf claimed credit for taking the country back to civilian rule. But he also issued a veiled warning to the new civil administration that it should not deviate from his policies. He said his 1999 takeover of the country saved Pakistan from a political crisis and that the incoming civilian government should build on his achievements. “The new government should pick up the reins of power with full resolve — the ray of hope which we have shown should be spread across the length and breadth of the country,” declared President Musharraf. President Musharraf was sworn in for another five-year term, the same day the parliament met for the first time since his coup. While promising that he would be handing over power to the newly elected civilian leader, the President made it crystal clear that he is still the final authority on most matters, particularly in foreign and economic policy issues.

Jamali, meanwhile, faces a tough challenge from a formidable and vocal opposition in parliament, particularly from the religious right, in defending the constitutional amendments that grant the President extensive powers and institutionalise the role of the army. The majority of the deputies, including some who voted for him, have rejected the changes and support a debate on the issue.

Jamali, meanwhile, faces a tough challenge from a formidable and vocal opposition in parliament, particularly from the religious right, in defending the constitutional amendments that grant the President extensive powers and institutionalise the role of the army. The majority of the deputies, including some who voted for him, have rejected the changes and support a debate on the issue.

The installation of an elected parliament and a civilian administration has radically changed the country’s political dynamics. Despite promises by Jamali to follow the line, many observers, predict intensifying conflict between the parliament and the President, not only on the issue of constitutional amendments, but also regarding his role as army chief. The Islamic leaders have warned that they will not accept a president in military uniform. “If General Musharraf is serious in handing over power to the elected representatives then he should announce his retirement from the post of army chief and withdraw all the unilateral amendments he made in the constitution,” said Qazi Hussain Ahmed, leader of the main opposition Islamic alliance. He has also called for the reversal of Pakistan’s support to the United States and the withdrawal of American troops from the country. “By allowing the United States to set up its bases and allowing the FBI to conduct raids on Pakistani soil, President Musharraf has sold the independence of the country,” said the Jamaat leader.

The MMA and the PPPP have identical views on the restoration of the constitution that existed before the military take-over. The widening differences between them, on foreign policy issues, particularly the government’s support to the United States in the war on terrorism, however, may give the beleagured government some respite. ” It will be a weak government and a very strong opposition,” said Khawaja Asif, a PML (N) leader.

After losing its fragile majority within a week, the government has reopened negotiations with the MMA, but it is too late for a deal as the constitution with the changes has already been enforced. President Musharraf’s stubbornness not to get the amendments ratified by parliament has threatened the new political set-up. “The President should understand he will also be removed if the system is wound up,” said a senior MMA leader. Despite it’s current weak position, the government may continue to survive for some time as the opposition is not in the position to form the government either.

Though MMA leaders have given assurances that they will not let the government fail, a major test for Jamali will come in two months time when he is required to take a vote of confidence in the National Assembly. The present political situation is similar to the 1950s, when governments would change overnight.

The political crisis deepened further with the continuing instability in Sindh, where the assembly session was arbitrarily postponed indefinitely after the failure of the pro-military group to form the government. Except for the Punjab, the PML (Q) have lost ground in the other two provinces. With the MMA forming the government in the NWFP as well as being a crucial political partner in the coalition in Balochistan, “Jabal Khan” faces a mountainous task ahead.

The writer is a senior journalist and author. He has been associated to the Newsline as senior editor at.