Colours of Harmony

By Ilona Yusuf | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 15 years ago

A recent exhibition at the PNCA in Islamabad featured prints by South and East Asian printmakers, along with works by local artists. The prints were originally exhibited between 2005 and 2007 in the major cities of Pakistan, as part of a larger show titled Contemporary Prints, Japan and East Asia. The motive behind this exhibition was to raise money for flood relief, but in keeping with her commitment to art education, the curator, Sabah Husain, spent a large chunk of time conducting gallery talks for art students and observers.

Looking West for new currents in modern art has become second nature to Pakistani artists. The curator differs in her belief that there are lessons to be learned by looking East. Trained in Japan as a printmaker in the 1980s, she feels that Pakistan shares commonalities with South and East Asian nations: Japan, China, Thailand, Indonesia and India. As Tanvir Ahmad Khan stated in his inaugural speech at the opening, “We are… struck by many similarities — similarities inherent in being located in a common post-colonial ethos, similarities embedded in challenges of globalisation and those generated by present day technological advances… there is a shared resonance of form, idiom and grammar. The…stressed conditions imposed by alien rule (have) been redressed only in varying degrees by our cultures and there is a great deal that we can learn from one and another. Our societies are dynamic; they look forward to a future of synthesis and fusion and not regression into any mythical past.”

Aptly spoken, because the work on display reflected skillful assimilation of traditional and modern themes and concepts. The Japanese artists have perhaps the most exposure to new methods in printmaking, and there was a wide variety of techniques used in the prints on display. But the compositional rules and treatment of space are rooted in local tradition, as in Ikeda Ryoji’s photo etchings, with their blocks of colour and form balanced against one another, each area divided off-centre. Yoshihara Hideo’s lithographs are composed of flat blocks of colour against negative space, with the addition of almost photographic renderings of faces. In ‘Sounds of Trees, Whispering People,’ we see the back of a head and shoulders, balanced against a typically Oriental tree form. It is as if the figure strains to hear something hidden in the air: the shadows of things past, or a wish to return to the centre of oneself. Thailand’s Phatyos Buddhacharoen’s masterfully controlled large lithographs are composed of single forms that handle concepts such as texture, weight and volume. ‘These Significant Abstract Forms,’ as they are titled, appear to float effortlessly in the negative space surrounding them, although they express the opposite attribute of solidity.

Aptly spoken, because the work on display reflected skillful assimilation of traditional and modern themes and concepts. The Japanese artists have perhaps the most exposure to new methods in printmaking, and there was a wide variety of techniques used in the prints on display. But the compositional rules and treatment of space are rooted in local tradition, as in Ikeda Ryoji’s photo etchings, with their blocks of colour and form balanced against one another, each area divided off-centre. Yoshihara Hideo’s lithographs are composed of flat blocks of colour against negative space, with the addition of almost photographic renderings of faces. In ‘Sounds of Trees, Whispering People,’ we see the back of a head and shoulders, balanced against a typically Oriental tree form. It is as if the figure strains to hear something hidden in the air: the shadows of things past, or a wish to return to the centre of oneself. Thailand’s Phatyos Buddhacharoen’s masterfully controlled large lithographs are composed of single forms that handle concepts such as texture, weight and volume. ‘These Significant Abstract Forms,’ as they are titled, appear to float effortlessly in the negative space surrounding them, although they express the opposite attribute of solidity.

Artists of each nation express, to some degree, the social conditions under which they live, whether they strive to uphold or change the system. Several of the Chinese prints appear to reflect the former socialist doctrine whereby the artist upholds the state’s ideology and what it seeks to achieve. These consist of finely executed lithographs and etchings of people, titled ‘Father and Son,’ ‘Sowing,’ and ‘Son of the Plateau.’ But the new work represents a departure, as in Zhou Jirong’s silkscreen and woodcut prints, which use themes that relate to rapid urbanisation and prosperity. In ‘Evolution Diagram — Bird,’ the elementary sketch of a bird also resembles the silhouette of an airplane, suspended above a view of a traffic-choked highway whose centre is occupied by a blot that rises towards the sky. Zhang Guanghui’s woodcuts titled ‘Washing Hair’ are modern in theme and treatment, each print composed of multiple layers and forms, so that the observer constantly meets a new face or figure among the various textures each time he looks at them. Ay Tjoe Christine and Tisna Sanjaya, both from Indonesia, a country with a colonial past like Pakistan, employ symbols and motifs from local theatre and drama, with its animistic traditions. Christine’s work, finely executed, sophisticated dry points are a contrast to Sanjaya’s deceptively naïve compositions, although both use similar terms of reference.

Artists of each nation express, to some degree, the social conditions under which they live, whether they strive to uphold or change the system. Several of the Chinese prints appear to reflect the former socialist doctrine whereby the artist upholds the state’s ideology and what it seeks to achieve. These consist of finely executed lithographs and etchings of people, titled ‘Father and Son,’ ‘Sowing,’ and ‘Son of the Plateau.’ But the new work represents a departure, as in Zhou Jirong’s silkscreen and woodcut prints, which use themes that relate to rapid urbanisation and prosperity. In ‘Evolution Diagram — Bird,’ the elementary sketch of a bird also resembles the silhouette of an airplane, suspended above a view of a traffic-choked highway whose centre is occupied by a blot that rises towards the sky. Zhang Guanghui’s woodcuts titled ‘Washing Hair’ are modern in theme and treatment, each print composed of multiple layers and forms, so that the observer constantly meets a new face or figure among the various textures each time he looks at them. Ay Tjoe Christine and Tisna Sanjaya, both from Indonesia, a country with a colonial past like Pakistan, employ symbols and motifs from local theatre and drama, with its animistic traditions. Christine’s work, finely executed, sophisticated dry points are a contrast to Sanjaya’s deceptively naïve compositions, although both use similar terms of reference.

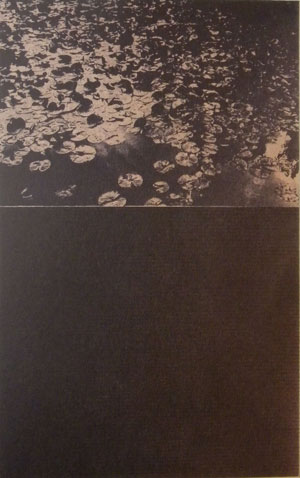

Zhou Jirong

It would be pertinent to note that nineteenth and early twentieth century artists from the West were fascinated by Japanese art. Van Gogh, Whistler, Pissarro, Gauguin, Lautrec, Degas and Mary Cassat; and architects of the Arts and Crafts Movement such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Charles Rennie Mackintosh incorporated various elements of Oriental art in their work. Japanese art consisted of off-centred arrangements with no perspective, light with no shadows and vibrant colours on plane surfaces. These forms and flat blocks of colour were the precursors to abstract art in modernism. And Ukiyo-e, Japanese woodcuts of the Edo period from the seventeenth to the twentieth century, inspired Art Nouveau, with their curved lines, patterned surfaces and contrasting voids and flatness of the picture-plane.

Sabah’s own work is an amalgam of sub-continental themes and forms married to Far Eastern sensibilities: the Japanese technique of elimination of extra detail to arrive at minimalist form, as well as the use of blocks of colour interspersed with negative space. The three prints on display were the precursor to a long lasting series on music and dance created during the 1980s.

M. F. Husain

Neighbouring India was represented by silkscreen prints by M. F. Husain. His elemental sketches are full of life, colour and meaning, with their symbols of freedom, justice, fertility and brotherhood. Calligraphy comes from Pakistan’s Ahmed Khan, whose compositions are a departure from conventional representations, focusing on the use of text to express abstract concepts rather than specific verses. Both works, in which shapes are formed of script, appear to represent the earth’s place within the universe. The elemental colours, applied beneath and over silver leaf overlaid with washes of tinted varnish, give the appearance of floating layers. The only truly figurative work in the exhibition is the oil on paper painting by Colin David, a preliminary study for a larger work.

While the work itself represents a commitment to excellence, the curator realises the importance of understanding the context and concepts behind it. She has brought the concept of gallery talks, a familiar phenomenon in the West, to her exhibitions. During the show, several schools and colleges, including NCA, were treated to these informal lectures. The way these lectures and the exhibition were conducted was in keeping with her contention that aspiring artists unable to travel abroad to view original works of art must have art brought to them, rather than making do with the limiting experience of looking at reproductions in books. This drive has taken up a large part of her time during the years since the ’90s, and continues to be a key element in the exhibitions curated by her as director of the Lahore Arts Foundation.