Another Bone of Contention

By Massoud Ansari | News & Politics | Published 20 years ago

Twenty-three year-old Abdul Samad arrived in Karachi from the commuter town of Crawley in Sussex about 18 months ago to study what he calls ‘deen’ or ‘the purest form of religion.’

Twenty-three year-old Abdul Samad arrived in Karachi from the commuter town of Crawley in Sussex about 18 months ago to study what he calls ‘deen’ or ‘the purest form of religion.’

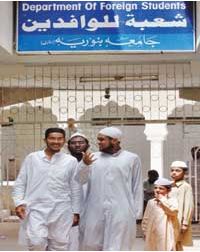

Living and studying at the Jamia Binoria in SITE, Karachi, one of Pakistan’s main Islamic seminaries — Samad intended to continue his religious education there for another five years in order to become an ‘alim’ or Islamic scholar, a title which confers upon the recipient the right to issue fatwas (religious edicts).

His plans for the future were, however, thrown into disarray after President Musharraf declared that all 1405 foreign students enrolled in the country’s religious seminaries were to be expelled. “All of them have to go,” Musharraf announced last month, as international pressure mounted on the Pakistan government from its western allies to reform the country’s madrassahs.

Samad became more serious about religion after his mother, Jahanara Begum’s death in 1994, while she was still in her mid-thirties. The Jamia Binoria seems a far cry indeed from the world of the “football crazy Liverpool supporter” who once sat on his family’s terrace house in West Sussex praising Britain’s “civilised” values. Today it is those very values he questions. “I’m rather shocked to hear Musharraf saying such things [against madrasshas],” said Samad in a his very British accent, as two mullahs from the school administration strained to figure out what he was saying. “As President of the country, he should underline who is doing wrong rather than generalising. I have been studying in this school for one-and-a-half years. If Musharraf can prove that I’m doing wrong, yes, I should be thrown out. But he has no right to brand all foreign students in seminaries militants, and throw them out.”

Samad maintains that seminaries have only one purpose: to prepare Muslim students for a life of propagating Islam. According to him, “For anyone who may want to follow Islamic jurisprudence in a traditional Islamic environment, Pakistan is the best place to come to.”

Certainly, religious schools abound in the country. According to official statistics, there are currently 16,059 high schools in Pakistan, while religious schools number about 15,000. The country’s total high school student population stands at 1.6 million, while madrassah students are estimated at 1.5 million. Of the latter, 1405 are foreigners, hailing from 56 different countries.

Eighty-one of the foreign students in local madaris are from Afghanistan, 42 are from America, 23 belong to the UK, over 20 to France, four are from Canada and there are an unaccounted number from Malaysia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand. Of the 1405 students, over 650 are studying in the province of Sindh. In addition to the 1405, there are also nearly 2,500 Afghan refugees who are enrolled in local seminaries.

Eighty-one of the foreign students in local madaris are from Afghanistan, 42 are from America, 23 belong to the UK, over 20 to France, four are from Canada and there are an unaccounted number from Malaysia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand. Of the 1405 students, over 650 are studying in the province of Sindh. In addition to the 1405, there are also nearly 2,500 Afghan refugees who are enrolled in local seminaries.

Since the 9/11 attacks, Washington has been seeking Pakistan’s cooperation in cracking down on madrassahs that are ideologically, and sometimes militarily, aligned with the Taliban and al-Qaeda remnants in the region. Now Britain, reeling from the July 7 suicide bombings in the heart of London, is also piling the pressure on Pakistan.

After it emerged that at least one, maybe two of the four 7/7 suicide bombers had visited one of Pakistan’s 15,000 Madrassahs, British Prime Minister Tony Blair asked Pakistan to “rein in these schools.” And in a recent statement, he condemned madrassah leaders who espouse extremist views and impart them to young students. “These roots go deep,” Blair said at a Downing Street meeting with Afghan President Hamid Karzai last month. “People are indoctrinated at a very, very early age … [they] go to some of these schools, these madrassahs, and they are given extreme teaching… Madrassah students end up in a situation where they actually believe that they are committing the will of God by killing innocent people.”

However, Abdul Samad, who was designated by the principal to speak on behalf of the more than 500 foreign students at his school disputes western notions that madrassahs are linked to terrorism. “They [the British and local authorities] have not yet established which school the [London bombers] went to,” he said. “Besides, how can one be indoctrinated within a span of just two months — the time the two suicide bombers are said to have spent in Pakistan.” Samad maintains the current anti-madrassah propaganda is a western ploy to tarnish the image of Islamic schools and Muslims. He contends that the west is not treating Muslims fairly and that non-whites are being discriminated against in the west. “Nationality is secondary now; it is only a colour that matters,” he maintained.

“Today, in England when they know you are a Muslim, they look at you in a negative way, some don’t even hesitate to call you a terrorist. Only recently, one of my friends was detained at Gatwick Airport for 24-hour questioning only because he is a Muslim,” he disclosed.

His resentment against what he sees as increasing discrimination against Muslims aside, Samad firmly condemns suicide bombing, no matter where in the world it is carried out. He maintains it causes Muslims more problems than they can solve. “It is basically the job of the army to fight [illegal] occupation, not that of individuals,” he contended.

It is interesting to observe how British-raised Samad has adapted so easily to his new environment. “When you see the benefit in something, it is not difficult to do,” he claimed. The bearded, kohl-eyed young man certainly seems at home in his traditional mid-calf length Arab-style djellaba, cap on head, saying his five times prayers and observing all the rituals that are considered Sunnah. “This is what God has ordained,” he maintained.

Samad’s stoic acceptance of what he sees as God’s commands aside, the regimen the Jamia Binoria has ordained for its students is stringently austere. TV and the internet are forbidden for students, as are newspapers. Boarders are awakened at about 3.00 a.m. for their tahajjud or midnight prayers, followed by morning or fajr prayers. Classes are held from 8.00 till 1.30 p.m. Apart from a recess of about two hours, the rest of the day comprises several study periods, and the boys go to bed at about 9.00 p.m., after the isha or night prayer.

Life at the seminary is certainly not for those without single-minded conviction. Yet hundreds of boys in their early teens to early twenties can be seen at the madrassah unflinchingly adhering to its discipline.

Said Samad, “It’s good to be here, not only because you are taught about religion, but also because you learn how to control your desires.” Samad, whose father runs a restaurant business in Sussex, disclosed he has two brothers and two sisters, but he is the only one in the family who has chosen to become a religious scholar. According to him his parents are happy with his decision and support him financially. “I’ve got a credit card and draw money whenever I need it. My parents happily pay my bills because they know that their son will become an alim,”he said. And if President Musharraf’s expulsion deadline for foreign students at madrassahs does not permit him to attain his goal in Pakistan, according to Samad, “I will not violate any law; I’ll just go somewhere else to pursue my objective.”

Samad is, of course, not the only one whose future is on the line. According to Mufti Naeem, who heads the Jamia Binoria, there are nearly 600 foreign students at his school — the highest number of foreigners at any seminary in the country.

Mufti Naeem said in the past the Jamia Binoria used to house between 900 to 1100 foreign students of diverse nationalities, but the number has drastically decreased in the last few years. “The number of foreign students could go up to 3,500 to 5,000 within a week’s time if permitted, as there are thousands of students from all over Europe who have expressed an interest in coming here, but we cannot entertain them due to visa restrictions,” maintained Mufti Naeem. He disclosed that there were at least 350 students from the UK alone who wanted to seek admission this year, but the Jamia Binoria could enrol only 15 of them because of visa problems for the rest.

Asked why he thinks his school is so much in demand, the Mufti responded, “I have no idea why so many students seek to come here and study religion. But what I have understood is that the more restrictions the west is imposing on religious institutions, the more inclined towards Islam people are becoming.”

As for how his school would respond to the call by Musharraf to expel foreign students, Mufti Naeem was somewhat vague when he responded, saying they had received some instructions recently, but would make a decision only after consulting the Shura or council of religious clergy. “We are basically thinking of how to react to this unjustified demand by the government,” he said, adding, however, that his school would definitely challenge the government’s policy in court. “It is a black law and we are confident that the court’s decision will go in our favour.”

For his part, Qazi Hussain Ahmed, the chief of the Jamaat-e-Islami, maintained, “If the government wants to throw out the foreign students in seminaries, they should also throw out all the foreigners who are acquiring education in other universities. You simply cannot have two laws — one for the students of religious schools, and another for those who are in government universities.”

Similarly, Maulana Fazlur Rehman, leader of the opposition in the National Assembly, declared that if the government tried to curb the liberty of religious schools, the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) would resign from the NWFP and National Assemblies. “We are ready to sacrifice everything to maintain the sovereignty of religious schools,” Fazlur Rehman announced.

And the Ittehad Tanzimat Madaris Deeniya (ITMD), an association comprising five madaris’ education boards affiliated with different schools of thought in the country, has decided to launch a campaign to mobilise public opinion in its support for countering the government’s new ‘anti-madrassah’ campaign.

The government, meanwhile, recently circulated a detailed questionaire through the police seeking information about the names and denomination of all masjids and madrassahs, their land position (whether they are housed on government property or private land, how much of the land is allotted, if there is any illegal possession or encroachment etc.), whether they have No-objection Certificates, the names, addresses and phone numbers of those in charge and of the teachers at each school, the number of students in each institution, with a breakdown of Pakistani and foreign students, with specific mention of the latter’s home countries, etc.

While the clergy seems to be on a collision course with the government on the issue, how serious Musharraf is about the implementation of the orders relating to madrassahs remains to be seen.

In 2000 the government bowed down to pressure from the clergy, because according to President Musharraf, he did not have the experience and security cover to take difficult decisions then. Now, as he himself acknowledges, the problem of ‘legitimacy’ no longer exists. So will he deliver?