Small Steps, Big Dreams

By I. A. Rehman | News & Politics | Published 22 years ago

Almost everybody in India and Pakistan is now talking about peace, though some still refer to the subject only to suggest preconditions to normalisation of relations between the two neighbours. This in itself is a happy change from the days when one only heard of the imminence of a devastating war in the sub-continent. But while optimism about peace prospects is growing and more and more people on both sides are taking a clearer stand on the need for amity, the air is not free from doubts that an era of peace between India and Pakistan might still not be about to begin.

The rise in optimism can be attributed to quite a few developments. The leaders of both India and Pakistan seem to be relishing the rhetoric of peaceful coexistence. India has been going through a process of unwinding itself. The unilateral steps it had taken after the December 2001 attack on the parliament house in New Delhi are being rescinded. New High Commissioners have assumed charge of their respective missions. The bus service between the two countries has resumed and negotiations for the restoration of rail and air links are underway.

New Delhi has also reconciled itself to the idea of the Pakistan military’s dominant role in this country’s politics. Reservations to bilateral talks have been softened, if not dropped altogether. The veto on the SAARC summit has been withdrawn. The response to fresh acts of terrorism in the Indian part of Kashmir, even a raid in which a Brigadier was killed, is that these incidents will not disrupt the movement towards normalisation of relations with Pakistan.

The only demand on Pakistan, not only by India but also the international community, has been that it must put an end to militants crossing the Line of Control from its side. Islamabad has received some credit for compliance, though violence in Kashmir has not ceased. Nor have New Delhi’s complaints ended. However, there is perhaps a greater recognition of the impossibility of securing a complete end to acts of militancy or terrorism. Quite a few autonomous actors are in the field and their capacity to undermine the peace initiative is manifest. It takes only a few who have a vested interest in stoking the fires of conflict, or simply in gun-running, to stage an act of terrorism and cause a setback to reconciliation efforts.

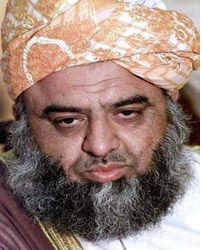

A considerable contribution to easing of tensions has been made by a fresh wave of people-to-people exchanges. Parliamentarians and business people have walked across the Wagah border checkpost in both directions. Young students from the two countries held a most impressive peace festival in Karachi. A joint meeting of parliamentarians and politicians in Islamabad is scheduled for August. Judges and lawyers as well as writers and trade unionists wish to exchange delegations. Nobody should discount the impact of Maulana Fazl-ur-Rahman’s visit to India. When a maulana with considerable following in the religious lobby calls upon the jihadis to put their arms aside and eschew violence, the advice cannot be dismissed as the ranting of an incorrigible secular democrat. His logic should strengthen the Pakistan regime’s hands if it wishes to control militancy in the Kashmir valley. And it is honey to BJP ears because it offers the party possibilities of securing the votes of the Jamiat Ulema-i-Hind followers.

However, nothing has helped the people of the two countries to recognise each other as human beings more than the successful surgery on the heart of a little Pakistani girl, Noor, at a Bangalore hospital. The two peoples came together to save life, and this underlined the need to share the ideal of saving life on the sub-continent. The peace activists on both sides received the gift of a new humanitarian argument to strengthen their brief.

However, nothing has helped the people of the two countries to recognise each other as human beings more than the successful surgery on the heart of a little Pakistani girl, Noor, at a Bangalore hospital. The two peoples came together to save life, and this underlined the need to share the ideal of saving life on the sub-continent. The peace activists on both sides received the gift of a new humanitarian argument to strengthen their brief.

Yet, a way of out the log-jam the governments of India and Pakistan have created for themselves cannot easily be seen on either side.

One major reason for this situation is that peace and good-neighbourly relations between India and Pakistan are presumed to be contingent upon the resolution of disputes or disagreements between them. This presumption needs to be reviewed. Normal relations follow settlement of disputes between any two parties when an appreciation of the basis of friendship between them predates the emergence of a dispute that sours their relationship. In such situations, the will or even the desire to normalise relations is sustained by positive memories of their pre-dispute ties and the recognition of mutual gain that will accrue by restoring status quo ante. These memories also facilitate resolution of disputes or disagreements. In the absence of a history of pre-dispute friendship or even a common interest, disputes become intractable, and even if they are somehow settled, normal ties based on shared interest do not necessarily follow.

The states of India and Pakistan have been behaving as organised forms of the Hindu and Muslim communities of the pre-independence period. These communities did have some periods of peaceful co-existence in the distant past. But memories of that experience were superseded by those of bitter acrimony over nearly two centuries. Both sides are determined, much against the demands of reason, to live in the past. They cannot recall any experience of living together in peace whose revival could be sought through removal of disagreements. This means there is no realisation, at least at the popular level, of the huge losses India and Pakistan have caused themselves by failing to compose their differences, losses that could be measured in terms of historical experience. The will for peace, therefore, lacks both strength and permanence.

Thus, in order to ensure that the two sub-continental neighbours will live in peace and find ways to a mutually beneficial relationship once the existing causes dividing them have been taken care of, they have to create a vision of life after settlement of disputes, a substitute for the historical experience they lack. There is thus urgent need to define the peace dividends for the benefit of the public on both sides, so that the exercise for settlement of disagreements is not viewed as an end in itself but assumes importance as the means to a welcome end.

It is unwise to put off the crafting of a shared vision of a peaceful South Asia till all the irritants to India-Pakistan normalisation have been removed, for the will to complete the clean-up job will not be adequately effective. Nor will there be a guarantee that new disagreements will not be discovered to sustain the traditional confrontation. Indeed, one new factor of discord is already developing in the form of India-Pakistan competition in Afghanistan. Even if a formula for peaceful and productive co-existence cannot be implemented without tackling bilateral disputes and disagreements, it is essential that both objectives are simultaneously pursued.

It is unwise to put off the crafting of a shared vision of a peaceful South Asia till all the irritants to India-Pakistan normalisation have been removed, for the will to complete the clean-up job will not be adequately effective. Nor will there be a guarantee that new disagreements will not be discovered to sustain the traditional confrontation. Indeed, one new factor of discord is already developing in the form of India-Pakistan competition in Afghanistan. Even if a formula for peaceful and productive co-existence cannot be implemented without tackling bilateral disputes and disagreements, it is essential that both objectives are simultaneously pursued.

A resolution of India-Pakistan differences demands willingness for give-and-take, in the political sense. If each side, or even one of them, seeks a settlement on terms traditionally advanced (although both India and Pakistan have now and then deviated from their “principled” positions), no happy accord will be possible. But the space for compromise has been eliminated by a most unfortunate ideologisation of the issues in contention. Ideology might not have been the decisive factor when a dispute or disagreement originated but circumstances and time can give even simple issues the halo of ideology. Kashmir is a classic example, and this matter will not be resolved until both sides show the courage to climb down from their ideological pedestals. Since there is no tradition of trust between New Delhi and Islamabad, each side is afraid of the slightest concession to the other side lest it entails prohibitive cost in domestic politics. The immediate political objectives before the present regimes in both countries will prevent them from allowing reason to prevail over their fears.

Whatever the terms one may choose to describe the Kashmir tangle, both sides recognise it as the biggest obstacle to normalisation. However, it should be clear to everybody that a final settlement of this issue is impossible in the present circumstances. This matter requires a process spread over a considerable period and a final solution will emerge only after India and Pakistan work out a fair framework for co-habiting their common land. At the moment they can do no more than launching of the required process by reaffirming certain principles: that Kashmir is not merely a territorial dispute between India and Pakistan, that the people of Jammu and Kashmir on both sides of the divide are the principal party whose voice must carry greater weight than that of New Delhi or Islamabad, that nobody has a right to divide a people against their wishes, and that all parties have an obligation to create conditions on both sides of the LOC in which the people are guaranteed protection against human rights abuses and assured freedom of expression and assembly so that they can think of their future in peace and decide how their will may be ascertained.

An interim accord on these principles should be accompanied by a hefty dose of confidence-building measures, preference being given to consolidating mutual goodwill without attempting steps that cause pain, real or imagined, to either side or ignore security concerns, again real or perceived. There may be much in Pakistan that the Indians dislike and there may be much in India that the Pakistanis claim to abhor. That is quite irrelevant. Neither side should aspire to change the other. No right can be invoked for entertaining such false dreams. The peoples of India and Pakistan have to accept and respect each other as they are and trust in time for a straightening out of their unwelcome angularities. They have denied the world their contribution to models of unity in diversity far too long. A great future lies before them if they can bury the past. The alternative is more of poverty, more of blind hatred, and assured mutual destruction.

Mr. I.A. Rehman is a writer and activist living in Pakistan. He is the secretary general of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan Secretariat.