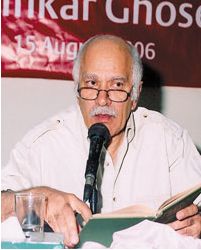

Interview: Zulfikar Ghose

By Hani Yousuf | Arts & Culture | Books | People | Q & A | Published 18 years ago

“There are only two kinds of writers, good writers and bad writers”

– Zulfikar Ghose

Q: When did you first come to Pakistan?

A: I first came here in 1961, with the English cricket team. I was reporting for The Observer. It gave me the opportunity to see all of Pakistan. That was pretty exciting, and it made me feel very much at home. In fact, had somebody offered me a job, I might have even stayed.

Before Partition we had been living in Bombay and after Partition we emigrated to England, and I became involved in my education. So 1961 was my first opportunity to come to Pakistan.

I landed in Karachi. I felt great. I happen to have some family members here and rather than staying with the cricket team, I stayed with them. And then from here we went to Lahore, then to Pindi and Lyallpur, which is now Faisalabad.

After I got married, my wife and I made a trip together. That was 16 years ago. We spent time in Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad. We went to Peshawar and took a trip to Taxila where I felt very much at home. In Taxila I felt as though my ancestors came from there. I had this funny spiritual experience.

Q: Did your ancestors come from Taxila?

A: Sometimes, I think that it is in our bloodstream, that there’s something in some little cell there that says something to our ear, says, that’s where you come from. Why else do we have this strange experience when we are in some landscape, that this is where we really belong.

We live in a part of the world where invasions over the last thousands of years came from different directions. Some centuries ago there were some people who were oppressed, and so they fled from the invaders and ended up in a valley in Kashmir, where my ancestors come from.

These wanderings that I have had across the country have given me a sense of belonging. The question that follows from there is, if you feel that attachment, then why don’t you come and stay here? Well, one is a creature of circumstance. One is a victim of economic and other kinds of realities, obligations that one has accumulated over the years. You abandon all of that just because you feel good in Taxila.

Q: What’s your favourite city in Pakistan?

A: I like Karachi because I grew up in Bombay. I like the sea air and I like the palm trees and the coconut trees, and the ocean always fills me with great happiness.

But I do like Lahore as well because of its wonderful trees. Also, I suppose being born a Punjabi, I have a certain warm feeling towards the capital of Punjab.

Q: Do you see any change for the better on this visit?

A: Young people like yourselves. It’s very thrilling to come across young people who are interested in the larger questions of reality and the world.

Q: In your interview with Feroza Jussawala and Reed Way Dasenbrock you said you weren’t “multicultural,” you were “British.”

A: That interview happened in my back garden. We had a big magnum of red wine that we were drinking while we were talking, and having a jolly good time. And when she said, “Multicultural writer like you,” I, in a slightly frivolous way, said, “I’m not multicultural, I’m British.”

There was this political correctness, multiculturalism, ethnicity etc. As far as I am concerned, human beings are human beings, writers are writers. There are only two kinds of writers, good writers and bad writers. I’m not a multicultural writer. I’m not a British writer. I am not a Pakistani writer. I’m not anything really, but myself. It’s the individual that matters at the end. It’s the individual that creates whatever is created, good or bad. But when somebody is successful, everybody is eager to claim that person

Q: Who is a good writer?

A: They’re all dead. It’s a long list, beginning from the Arabian Nights, going back to Boccacio. Milan Kundera says, “Cervantes is the father of us all.” Without Cervantes, none of us would be writing the novel as we do.

Q: The study of literature is becoming increasingly specialised. It’s become all about taking the Marxist approach, or the feminist approach, or the post-structural and so on.

A: Why do they have to teach you from that point of view? Because they can appear to be important. Because they can give you jargon, as though they are expressing the profoundest wisdom. In fact, it is nonsense, much of it. I’ve looked at Derrida, and I go to sleep. If the teachers of literature did not have these props they would have nothing to say. But I do know some very fine teachers who know all that Derrida stuff and make good use of it.

Q: What do you think of Freud?

A: I no longer take Freud as seriously as I took him when I first came across him. I did read the interpretation of dreams, civilisation and its discontent. I think the cities have been dismissive of much of Freud’s emphasis on early sexuality. He has been discredited in many ways. But he’s important because he’s part of human consciousness now.

Freud bases his interpretation on his clients based in Vienna and later in London, whereas Jung studies the entire world and all primitive societies and their mythologies and folklore. Out of that he builds his great structure of the collective unconscious and what he calls racial memory.

Jung is one of the prominent influences in my life. I do a lot of working around with images that become symbols. He continues to be of greater stature than before, while Freud seems to diminish.

Q: How do you see the situation playing out in Balochistan post the recent developments?

A: I’m not a politician and I don’t have a crystal ball to gaze into and predict the future, but given what is transpiring, I don’t see any future for this country, and I don’t see any future for Balochistan or the Baloch people in this country.

Q: What about Nabokov, Beckett and Conrad?

A: You’ve hit upon three of my most important antecedents — for the use of language, for the creation of style, for the techniques and forms they have created.

Q: What about the advent of the South Asian novel?

A: There’s no such thing as the African novel or the South Asian novel. The fact is that we’re writing in the English language. And if the content of the novel is from here, it’s because I am from here. “I,” am always “I,” wherever you are.

You’re writing in the English language, therefore essentially you’re writing the European novel. Without having Cervantes as your father you’re not going to be able to write a good novel. So there’s nothing special about any area, except that it’s my area. So let us forget about these labels, and these categories. Let us free ourselves.

Q: How do you teach creative writing?

A: By not teaching it at all! Anyways, I start with texts. And the first texts are Flannery O’Connor and then Chekhov, the old-fashioned stuff. After about three or four of those, they know what they’re doing. Then I give them experimental examples. Over the years, I have accumulated a number of examples from my former students, some of which are extraordinary.

Language is a variety of things. If you want to write the well-made story forever, go ahead and do it, but make sure it is well done. You can experiment as well. At the next stage, I give them texts of the stories, people like Joyce Carol Oates, Samuel Beckett, and a number of other really important writers of our time.

Most people who write a story, think all they need is a formula. They don’t need a formula, they need to understand what their brain is about. Because each one of us has a different brain. We are individuals. And when we say we like a work of art, it’s because the individual has shown us something which nobody else has done.

You produce that as something which comes naturally from you after a great deal of labour. And that labour is a lot of reading, a lot of writing, and suddenly you say, ah this is what I really want to do.

The reading of other writers’ essays, letters, other texts, is very, very important. I make them read that and then they write their own stories in that context. I get some very good results because of that, rather than using a textbook that says, oh, we will do a plot this week.

Q: In your interview with Feroza Jussawala and Reed Way Dasenbrock, you also said, “Ideas don’t help anyone, things do. Things like penicillin and flushing toilets.” A work of art is a thing. What is its utilitarian purpose?

A: None at all. It’s an object somebody makes and leaves behind. You pick it up, you enjoy it or you don’t enjoy it. But there are some who say, “Oh, but we have to bring it to the workers and we have to improve people.” Hamlet does not improve anybody and Hamlet is one of the greatest things there is.

Q: Have you read any Pakistani writers?

A: Yes, I have, but don’t ask me the names of who are the good ones and who are the bad ones, because if I say who the good ones are, the bad ones will say, “Oh, he didn’t mention me.” So I had better not say anything.

Q: But you think there is good quality work being produced?

A: Oh, excellent. I would also say that some of the best work in the English language in the last 30 years has come from Pakistan, India, Australia, Canada, one or two African and Caribbean writers. Of course, there is some very good work from the English, some very good work from the Americans, but I do think that the English language has greatly benefited from and has been nurtured by the slightly different nuances that are expressed in the writing that comes from this part of the world.

Even if some of us from Pakistan are living in Texas or wherever, there is something within our bloodstream, our chemistry, our brain structure that makes us create certain rhythms that the English writer would never do. Therefore, the English language has been enriched by all these forces.

Q: Are you a novelist, critic, poet, or short story writer?

A: Just a human being who is obsessed with words, perhaps, or wakes up every day to try to make some sense of the reality around him and to create a new image for that reality. Sometimes it comes through in a sentence, in a story or a phrase in a poem, or in the expression of some idea in an essay.

Hani Yousuf started her career at Newsline Magazine in 2006. Since then, she has completed a Master's in Journalism at Columbia University and reported and written for magazines and newspapers in Germany, the US and the South Asian region. She is now a PR consultant, based in Karachi.